Binding Objective-C libraries

When working with Xamarin.iOS or Xamarin.Mac, you might encounter cases where you want to consume a third-party Objective-C library. In those situations, you can use Xamarin Binding Projects to create a C# binding to the native Objective-C libraries. The project uses the same tools that we use to bring the iOS and Mac APIs to C#.

This document describes how to bind Objective-C APIs, if you are binding just C APIs, you should use the standard .NET mechanism for this, the P/Invoke framework. Details on how to statically link a C library are available on the Linking Native Libraries page.

See our companion Binding Types Reference Guide. Additionally, if you want to learn more about what happens under the hood, check our Binding Overview page.

Bindings can be built for both iOS and Mac libraries. This page describes how to work on an iOS binding, however Mac bindings are very similar.

Sample Code for iOS

You can use the iOS Binding Sample project to experiment with bindings.

Getting started

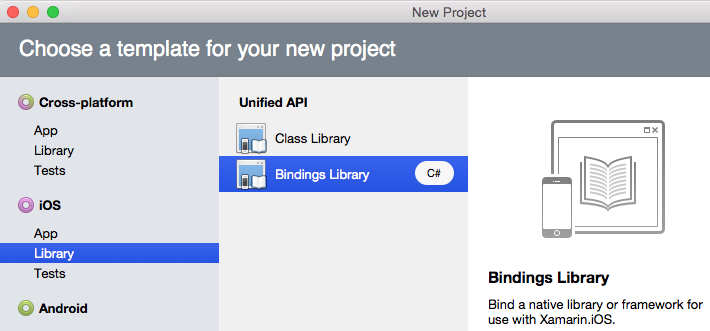

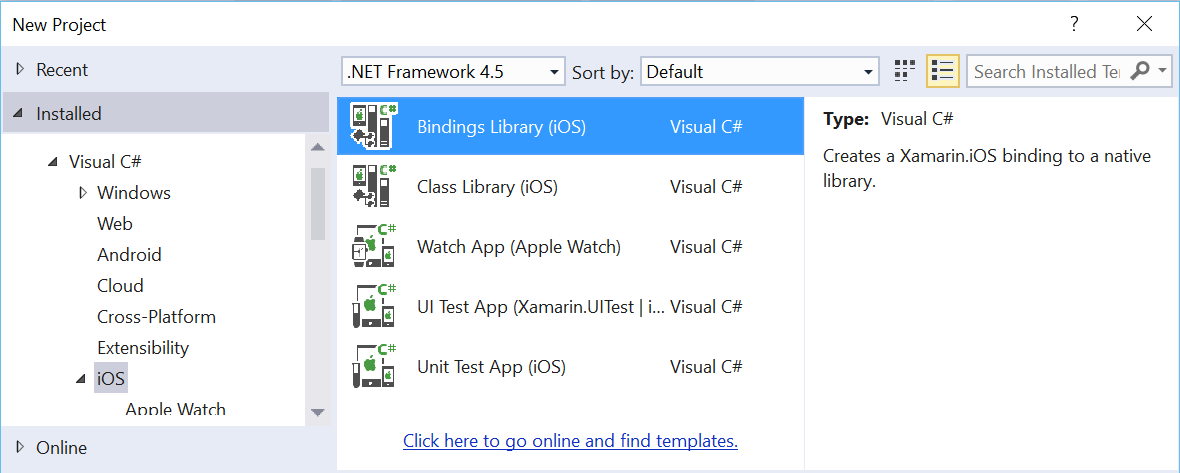

The easiest way to create a binding is to create a Xamarin.iOS Binding Project. You can do this from Visual Studio for Mac by selecting the project type, iOS > Library > Bindings Library:

The generated project contains a small template that you can edit, it

contains two files: ApiDefinition.cs and StructsAndEnums.cs.

The ApiDefinition.cs is where you will define the API contract, this

is the file that describes how the underlying Objective-C API is

projected into C#. The syntax and contents of this file are the main

topic of discussion of this document and the contents of it are

limited to C# interfaces and C# delegate declarations. The

StructsAndEnums.cs file is the file where you will enter any

definitions that are required by the interfaces and delegates. This

includes enumeration values and structures that your code might use.

Binding an API

To do a comprehensive binding, you will want to understand the Objective-C API definition and familiarize yourself with the .NET Framework Design guidelines.

To bind your library you will typically start with an API definition file. An API definition file is merely a C# source file that contains C# interfaces that have been annotated with a handful of attributes that help drive the binding. This file is what defines what the contract between C# and Objective-C is.

For example, this is a trivial api file for a library:

using Foundation;

namespace Cocos2D {

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface Camera {

[Static, Export ("getZEye")]

nfloat ZEye { get; }

[Export ("restore")]

void Restore ();

[Export ("locate")]

void Locate ();

[Export ("setEyeX:eyeY:eyeZ:")]

void SetEyeXYZ (nfloat x, nfloat y, nfloat z);

[Export ("setMode:")]

void SetMode (CameraMode mode);

}

}

The above sample defines a class called Cocos2D.Camera that derives

from the NSObject base type (this type comes from

Foundation.NSObject) and which defines a static property

(ZEye), two methods that take no arguments and a method that takes

three arguments.

An in-depth discussion of the format of the API file and the attributes that you can use is covered in the API definition file section below.

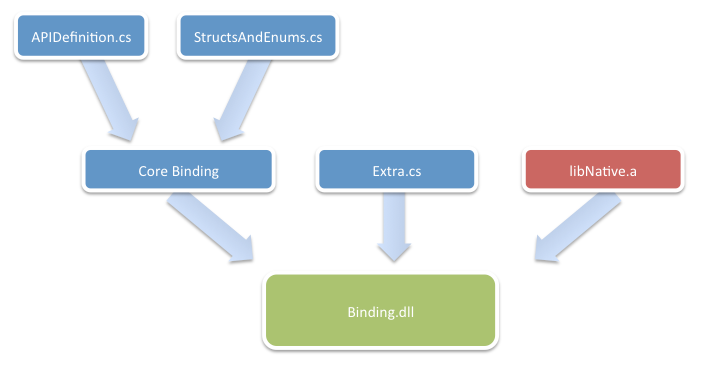

To produce a complete binding, you will typically deal with four components:

- The API definition file (

ApiDefinition.csin the template). - Optional: any enums, types, structs required by the API definition file (

StructsAndEnums.csin the template). - Optional: extra sources that might expand the generated binding, or provide a more C# friendly API (any C# files that you add to the project).

- The native library that you are binding.

This chart shows the relationship between the files:

The API Definition file will only contain namespaces and interface definitions (with any members that an interface can contain), and should not contain classes, enumerations, delegates or structs. The API definition file is merely the contract that will be used to generate the API.

Any extra code that you need like enumerations or supporting classes

should be hosted on a separate file, in the example above the

"CameraMode" is an enumeration value that does not exist in the CS

file and should be hosted in a separate file, for example

StructsAndEnums.cs:

public enum CameraMode {

FlyOver, Back, Follow

}

The APIDefinition.cs file is combined with the StructsAndEnum class

and are used to generate the core binding of the library. You can use

the resulting library as-is, but typically, you will want to tune the

resulting library to add some C# features for the benefit of your

users. Some examples include implementing a ToString() method, provide

C# indexers, add implicit conversions to and from some native types or

provide strongly-typed versions of some methods. These improvements

are stored in extra C# files. Merely add the C# files to your project

and they will be included in this build process.

This shows how you would implement the code in your Extra.cs

file. Notice that you will be using partial classes as these augment

the partial classes that are generated from the combination of the

ApiDefinition.cs and the StructsAndEnums.cs core binding:

public partial class Camera {

// Provide a ToString method

public override string ToString ()

{

return String.Format ("ZEye: {0}", ZEye);

}

}

Building the library will produce your native binding.

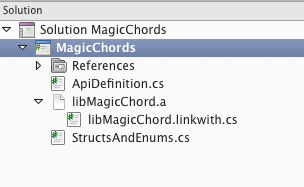

To complete this binding, you should add the native library to the project. You can do this by adding the native library to your project, either by dragging and dropping the native library from Finder onto the project in the solution explorer, or by right-clicking the project and choosing Add > Add Files to select the native library. Native libraries by convention start with the word "lib" and end with the extension ".a". When you do this, Visual Studio for Mac will add two files: the .a file and an automatically populated C# file that contains information about what the native library contains:

The contents of the libMagicChord.linkwith.cs file has information about how

this library can be used and instructs your IDE to package this binary into

the resulting DLL file:

using System;

using ObjCRuntime;

[assembly: LinkWith ("libMagicChord.a", SmartLink = true, ForceLoad = true)]

Full details about how to use the

[LinkWith]

attribute are documented in the

Binding Types Reference Guide.

Now when you build the project you will end up with a MagicChords.dll file

that contains both the binding and the native library. You can distribute this

project or the resulting DLL to other developers for their own use.

Sometimes you might find that you need a few enumeration values, delegate definitions or other types. Do not place those in the API definitions file, as this is merely a contract

The API definition file

The API definition file consists of a number of interfaces. The interfaces in

the API definition will be turned into a class declaration and they must be

decorated with the [BaseType] attribute to specify the base class for the class.

You might be wondering why we did not use classes instead of interfaces for the contract definition. We picked interfaces because it allowed us to write the contract for a method without having to supply a method body in the API definition file, or having to supply a body that had to throw an exception or return a meaningful value.

But since we are using the interface as a skeleton to generate a class we had to resort to decorating various parts of the contract with attributes to drive the binding.

Binding methods

The simplest binding you can do is to bind a method. Just declare a

method in the interface with the C# naming conventions and decorate

the method with the

[Export]

attribute. The [Export]

attribute is what links your C# name with the Objective-C name in the

Xamarin.iOS runtime. The parameter of the

[Export]

attribute is the name of the Objective-C selector. Some examples:

// A method, that takes no arguments

[Export ("refresh")]

void Refresh ();

// A method that takes two arguments and return the result

[Export ("add:and:")]

nint Add (nint a, nint b);

// A method that takes a string

[Export ("draw:atColumn:andRow:")]

void Draw (string text, nint column, nint row);

The above samples show how you can bind instance methods. To bind static

methods, you must use the [Static]

attribute, like this:

// A static method, that takes no arguments

[Static, Export ("beep")]

void Beep ();

This is required because the contract is part of an interface, and interfaces

have no notion of static vs instance declarations, so it is necessary once again

to resort to attributes. If you want to hide a particular method from the

binding, you can decorate the method with the [Internal] attribute.

The btouch-native command will introduce checks for reference parameters to

not be null. If you want to allow null values for a particular

parameter, use the

[NullAllowed]

attribute on the parameter, like this:

[Export ("setText:")]

string SetText ([NullAllowed] string text);

When exporting a reference type, with the [Export]

keyword you can also specify the allocation semantics. This is necessary to ensure that no data is

leaked.

Binding properties

Just like methods, Objective-C properties are bound using the

[Export]

attribute and map directly to C# properties. Just like methods,

properties can be decorated with the

[Static]

and the

[Internal]

attributes.

When you use the [Export]

attribute on a property under the covers btouch-native actually binds two methods: the getter and the setter. The name

that you provide to export is the basename and the setter is

computed by prepending the word "set", turning the first letter of the

basename into upper case and making the selector take an

argument. This means that [Export ("label")] applied on a property

actually binds the "label" and "setLabel:" Objective-C methods.

Sometimes the Objective-C properties do not follow the pattern

described above and the name is manually overwritten. In those cases

you can control the way that the binding is generated by using the

[Bind]

attribute on the getter or setter, for example:

[Export ("menuVisible")]

bool MenuVisible { [Bind ("isMenuVisible")] get; set; }

This then binds "isMenuVisible" and "setMenuVisible:". Optionally, a property can be bound using the following syntax:

[Category, BaseType(typeof(UIView))]

interface UIView_MyIn

{

[Export ("name")]

string Name();

[Export("setName:")]

void SetName(string name);

}

Where the getter and setter are explicitly defined as in the name and setName bindings above.

In addition to support for static properties using

[Static], you can

decorate thread-static properties with

[IsThreadStatic],

for example:

[Export ("currentRunLoop")][Static][IsThreadStatic]

NSRunLoop Current { get; }

Just like methods allow some parameters to be flagged with

[NullAllowed],

you can apply

[NullAllowed]

to a property to indicate that null is a valid value for the property,

for example:

[Export ("text"), NullAllowed]

string Text { get; set; }

The [NullAllowed]

parameter can also be specified directly on the setter:

[Export ("text")]

string Text { get; [NullAllowed] set; }

Caveats of binding custom controls

The following caveats should be considered when setting up the binding for a custom control:

- Binding properties must be static - When defining the binding of properties, the

[Static]attribute must be used. - Property names must match exactly - The name used to bind the property must match the name of the property in the custom control exactly.

- Property types must match exactly - The variable type used to bind the property must match the type of the property in the custom control exactly.

- Breakpoints and the getter/setter - Breakpoints placed in the getter or setter methods of the property will never be hit.

- Observe Callbacks - You will need to use observation callbacks to be notified of changes in the property values of custom controls.

Failure to observe any of the above listed caveats can result in the binding silently failing at runtime.

Objective-C mutable pattern and properties

Objective-C frameworks use an idiom where some classes are immutable with

a mutable subclass. For example NSString is the immutable version,

while NSMutableString is the subclass that allows mutation.

In those classes it is common to see the immutable base class contain properties with a getter, but no setter. And for the mutable version to introduce the setter. Since this is not really possible with C#, we had to map this idiom into an idiom that would work with C#.

The way that this is mapped to C# is by adding both the getter and the

setter on the base class, but flagging the setter with a

[NotImplemented]

attribute.

Then, on the mutable subclass, you use the

[Override]

attribute on the property to ensure that the property is actually overriding

the parent's behavior.

Example:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface MyTree {

string Name { get; [NotImplemented] set; }

}

[BaseType (typeof (MyTree))]

interface MyMutableTree {

[Override]

string Name { get; set; }

}

Binding constructors

The btouch-native tool will automatically generate fours

constructors in your class, for a given class Foo, it generates:

Foo (): the default constructor (maps to Objective-C's "init" constructor)Foo (NSCoder): the constructor used during deserialization of NIB files (maps to Objective-C's "initWithCoder:" constructor).Foo (IntPtr handle): the constructor for handle-based creation, this is invoked by the runtime when the runtime needs to expose a managed object from an unmanaged object.Foo (NSEmptyFlag): this is used by derived classes to prevent double initialization.

For constructors that you define, they need to be declared using the

following signature inside the Interface definition: they must return

an IntPtr value and the name of the method should be Constructor. For

example to bind the initWithFrame: constructor, this is what you would

use:

[Export ("initWithFrame:")]

IntPtr Constructor (CGRect frame);

Binding protocols

As described in the API design document, in the section discussing

Models and Protocols,

Xamarin.iOS maps the Objective-C protocols into classes that have been

flagged with the

[Model]

attribute. This is typically used when implementing Objective-C

delegate classes.

The big difference between a regular bound class and a delegate class is that the delegate class might have one or more optional methods.

For example consider the UIKit class UIAccelerometerDelegate, this is

how it is bound in Xamarin.iOS:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

[Model][Protocol]

interface UIAccelerometerDelegate {

[Export ("accelerometer:didAccelerate:")]

void DidAccelerate (UIAccelerometer accelerometer, UIAcceleration acceleration);

}

Since this is an optional method on the definition for

UIAccelerometerDelegate there is nothing else to do. But if there was

a required method on the protocol, you should add the

[Abstract]

attribute to the method. This will force the user of the

implementation to actually provide a body for the method.

In general, protocols are used in classes that respond to messages. This is typically done in Objective-C by assigning to the "delegate" property an instance of an object that responds to the methods in the protocol.

The convention in Xamarin.iOS is to support both the Objective-C

loosely-coupled style where any instance of an NSObject can be

assigned to the delegate, and to also expose a strongly-typed version

of it. For this reason, we typically provide both a Delegate

property that is strongly typed and a WeakDelegate that is

loosely typed. We usually bind the loosely-typed version with

[Export],

and we use the [Wrap]

attribute to provide the strongly-typed version.

This shows how we bound the UIAccelerometer class:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface UIAccelerometer {

[Static] [Export ("sharedAccelerometer")]

UIAccelerometer SharedAccelerometer { get; }

[Export ("updateInterval")]

double UpdateInterval { get; set; }

[Wrap ("WeakDelegate")]

UIAccelerometerDelegate Delegate { get; set; }

[Export ("delegate", ArgumentSemantic.Assign)][NullAllowed]

NSObject WeakDelegate { get; set; }

}

New in MonoTouch 7.0

Starting with MonoTouch 7.0 a new and improved protocol binding functionality has been incorporated. This new support makes it simpler to use Objective-C idioms for adopting one or more protocols in a given class.

For every protocol definition MyProtocol in Objective-C, there is

now an IMyProtocol interface that lists all the required methods

from the protocol, as well as an extension class that provides all the

optional methods. The above, combined with new support in the Xamarin

Studio editor allows developers to implement protocol methods without

having to use the separate subclasses of the previous abstract model

classes.

Any definition that contains the

[Protocol] attribute will actually

generate three supporting classes that vastly improve the way that you

consume protocols:

// Full method implementation, contains all methods

class MyProtocol : IMyProtocol {

public void Say (string msg);

public void Listen (string msg);

}

// Interface that contains only the required methods

interface IMyProtocol: INativeObject, IDisposable {

[Export ("say:")]

void Say (string msg);

}

// Extension methods

static class IMyProtocol_Extensions {

public static void Optional (this IMyProtocol this, string msg);

}

}

The class implementation provides a complete abstract class that you can override individual methods of and get full type safety. But due to C# not supporting multiple inheritance, there are scenarios where you might needs to have a different base class, but you still want to implement an interface, that is where the

The generated interface definition comes in. It is an interface that has all the required methods from the protocol. This allows developers that want to implement your protocol to merely implement the interface. The runtime will automatically register the type as adopting the protocol.

Notice that the interface only lists the required methods and does

expose the optional methods. This means that classes that adopt the

protocol will get full type checking for the required methods, but

will have to resort to weak typing (manually using

[Export]

attributes and matching the signature) for the optional protocol methods.

To make it convenient to consume an API that uses protocols, the binding tool also will produce an extensions method class that exposes all of the optional methods. This means that as long as you are consuming an API, you will be able to treat protocols as having all the methods.

If you want to use the protocol definitions in your API, you will need to write skeleton empty interfaces in your API definition. If you want to use the MyProtocol in an API, you would need to do this:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

[Model, Protocol]

interface MyProtocol {

// Use [Abstract] when the method is defined in the @required section

// of the protocol definition in Objective-C

[Abstract]

[Export ("say:")]

void Say (string msg);

[Export ("listen")]

void Listen ();

}

interface IMyProtocol {}

[BaseType (typeof(NSObject))]

interface MyTool {

[Export ("getProtocol")]

IMyProtocol GetProtocol ();

}

The above is needed because at binding time the IMyProtocol would not

exist, that is why you need to provide an empty interface.

Adopting protocol-generated interfaces

Whenever you implement one of the interfaces generated for the protocols, like this:

class MyDelegate : NSObject, IUITableViewDelegate {

nint IUITableViewDelegate.GetRowHeight (nint row) {

return 1;

}

}

The implementation for the required interface methods gets exported with the proper name, so it is equivalent to this:

class MyDelegate : NSObject, IUITableViewDelegate {

[Export ("getRowHeight:")]

nint IUITableViewDelegate.GetRowHeight (nint row) {

return 1;

}

}

This will work for all required protocol members, but there is a special case with optional selectors to be aware of. Optional protocol members are treated identically when using the base class:

public class UrlSessionDelegate : NSUrlSessionDownloadDelegate {

public override void DidWriteData (NSUrlSession session, NSUrlSessionDownloadTask downloadTask, long bytesWritten, long totalBytesWritten, long totalBytesExpectedToWrite)

but when using the protocol interface it is required to add the [Export]. The IDE will add it via autocomplete when you add it starting with override.

public class UrlSessionDelegate : NSObject, INSUrlSessionDownloadDelegate {

[Export ("URLSession:downloadTask:didWriteData:totalBytesWritten:totalBytesExpectedToWrite:")]

public void DidWriteData (NSUrlSession session, NSUrlSessionDownloadTask downloadTask, long bytesWritten, long totalBytesWritten, long totalBytesExpectedToWrite)

There is a slight behavior difference between the two at runtime.

- Users of the base class (NSUrlSessionDownloadDelegate in example) provides all required and optional selectors, returning reasonable default values.

- Users of the interface (INSUrlSessionDownloadDelegate in example) only respond to the exact selectors provided.

Some rare classes can behave differently here. In almost all cases however it is safe to use either.

Binding class extensions

In Objective-C it is possible to extend classes with new methods,

similar in spirit to C#'s extension methods. When one of these methods

is present, you can use the

[BaseType]

attribute to flag the method as being the receiver of the Objective-C message.

For example, in Xamarin.iOS we bound the extension methods that are defined on

NSString when UIKit is imported as methods in the NSStringDrawingExtensions, like this:

[Category, BaseType (typeof (NSString))]

interface NSStringDrawingExtensions {

[Export ("drawAtPoint:withFont:")]

CGSize DrawString (CGPoint point, UIFont font);

}

Binding Objective-C argument lists

Objective-C supports variadic arguments. For example:

- (void) appendWorkers:(XWorker *) firstWorker, ...

NS_REQUIRES_NIL_TERMINATION ;

To invoke this method from C# you will want to create a signature like this:

[Export ("appendWorkers"), Internal]

void AppendWorkers (Worker firstWorker, IntPtr workersPtr)

This declares the method as internal, hiding the above API from users, but exposing it to the library. Then you can write a method like this:

public void AppendWorkers(params Worker[] workers)

{

if (workers is null)

throw new ArgumentNullException ("workers");

var pNativeArr = Marshal.AllocHGlobal(workers.Length * IntPtr.Size);

for (int i = 1; i < workers.Length; ++i)

Marshal.WriteIntPtr (pNativeArr, (i - 1) * IntPtr.Size, workers[i].Handle);

// Null termination

Marshal.WriteIntPtr (pNativeArr, (workers.Length - 1) * IntPtr.Size, IntPtr.Zero);

// the signature for this method has gone from (IntPtr, IntPtr) to (Worker, IntPtr)

WorkerManager.AppendWorkers(workers[0], pNativeArr);

Marshal.FreeHGlobal(pNativeArr);

}

Binding fields

Sometimes you will want to access public fields that were declared in a library.

Usually these fields contain strings or integers values that must be referenced. They are commonly used as string that represent a specific notification and as keys in dictionaries.

To bind a field, add a property to your interface definition file, and

decorate the property with the [Field] attribute. This attribute takes one parameter: the C name of the

symbol to lookup. For example:

[Field ("NSSomeEventNotification")]

NSString NSSomeEventNotification { get; }

If you want to wrap various fields in a static class that does not

derive from NSObject, you can use the

[Static]

attribute on the class, like this:

[Static]

interface LonelyClass {

[Field ("NSSomeEventNotification")]

NSString NSSomeEventNotification { get; }

}

The above will generate a LonelyClass which does not derive from

NSObject and will contain a binding to the NSSomeEventNotification

NSString exposed as an NSString.

The [Field]

attribute can be applied to the following data types:

NSStringreferences (read-only properties only)NSArrayreferences (read-only properties only)- 32-bit ints (

System.Int32) - 64-bit ints (

System.Int64) - 32-bit floats (

System.Single) - 64-bit floats (

System.Double) System.Drawing.SizeFCGSize

In addition to the native field name, you can specify the library name where the field is located, by passing the library name:

[Static]

interface LonelyClass {

[Field ("SomeSharedLibrarySymbol", "SomeSharedLibrary")]

NSString SomeSharedLibrarySymbol { get; }

}

If you are linking statically, there is no library to bind to, so you

need to use the __Internal name:

[Static]

interface LonelyClass {

[Field ("MyFieldFromALibrary", "__Internal")]

NSString MyFieldFromALibrary { get; }

}

Binding enums

You can add enum directly in your binding files to makes it easier

to use them inside API definitions - without using a different source

file (that needs to be compiled in both the bindings and the final

project).

Example:

[Native] // needed for enums defined as NSInteger in ObjC

enum MyEnum {}

interface MyType {

[Export ("initWithEnum:")]

IntPtr Constructor (MyEnum value);

}

It is also possible to create your own enums to replace NSString

constants. In this case the generator will automatically create the

methods to convert enums values and NSString constants for you.

Example:

enum NSRunLoopMode {

[DefaultEnumValue]

[Field ("NSDefaultRunLoopMode")]

Default,

[Field ("NSRunLoopCommonModes")]

Common,

[Field (null)]

Other = 1000

}

interface MyType {

[Export ("performForMode:")]

void Perform (NSString mode);

[Wrap ("Perform (mode.GetConstant ())")]

void Perform (NSRunLoopMode mode);

}

In the above example you could decide to decorate void Perform (NSString mode);

with an [Internal]

attribute. This will hide the constant-based API from your binding consumers.

However this would limit subclassing the type as the nicer API alternative

uses a [Wrap]

attribute. Those generated methods are not virtual, i.e.

you won't be able to override them - which may, or not, be a good choice.

An alternative is to mark the original, NSString-based, definition as

[Protected]. This will allow subclassing to work, when required, and

the wrap'ed version will still work and call the overriden method.

Binding NSValue, NSNumber, and NSString to a better type

The [BindAs] attribute allows binding NSNumber, NSValue and NSString(enums) into more accurate C# types. The attribute can be used to create better, more accurate, .NET API over the native API.

You can decorate methods (on return value), parameters and properties with

[BindAs].

The only restriction is that your member must not be inside a

[Protocol]

or [Model]

interface.

For example:

[return: BindAs (typeof (bool?))]

[Export ("shouldDrawAt:")]

NSNumber ShouldDraw ([BindAs (typeof (CGRect))] NSValue rect);

Would output:

[Export ("shouldDrawAt:")]

bool? ShouldDraw (CGRect rect) { ... }

Internally we will do the bool? <-> NSNumber and CGRect <-> NSValue conversions.

[BindAs] also supports arrays of NSNumber NSValue and NSString(enums).

For example:

[BindAs (typeof (CAScroll []))]

[Export ("supportedScrollModes")]

NSString [] SupportedScrollModes { get; set; }

Would output:

[Export ("supportedScrollModes")]

CAScroll [] SupportedScrollModes { get; set; }

CAScroll is a NSString backed enum, we will fetch the right NSString value and handle the type conversion.

Please see the [BindAs]

documentation to see supported conversion types.

Binding notifications

Notifications are messages that are posted to the

NSNotificationCenter.DefaultCenter and are used as a mechanism to

broadcast messages from one part of the application to

another. Developers subscribe to notifications typically using the

NSNotificationCenter's

AddObserver

method. When an application posts a message to the notification

center, it typically contains a payload stored in the

NSNotification.UserInfo

dictionary. This dictionary is weakly typed, and getting information

out of it is error prone, as users typically need to read in the

documentation which keys are available on the dictionary and the types

of the values that can be stored in the dictionary. The presence of

keys sometimes is used as a boolean as well.

The Xamarin.iOS binding generator provides support for developers to

bind notifications. To do this, you set the

[Notification]

attribute on a property that has been also been tagged with a

[Field]

property (it can be public or private).

This attribute can be used without arguments for notifications that

carry no payload, or you can specify a System.Type that references

another interface in the API definition, typically with the name

ending with "EventArgs". The generator will turn the interface into a

class that subclasses EventArgs and will include all of the properties

listed there. The [Export]

attribute should be used in the EventArgs class to list the name of the key

used to look up the Objective-C dictionary to fetch the value.

For example:

interface MyClass {

[Notification]

[Field ("MyClassDidStartNotification")]

NSString DidStartNotification { get; }

}

The above code will generate a nested class MyClass.Notifications with

the following methods:

public class MyClass {

[..]

public Notifications {

public static NSObject ObserveDidStart (EventHandler<NSNotificationEventArgs> handler)

}

}

Users of your code can then easily subscribe to notifications posted to the NSDefaultCenter by using code like this:

var token = MyClass.Notifications.ObserverDidStart ((notification) => {

Console.WriteLine ("Observed the 'DidStart' event!");

});

The returned value from ObserveDidStart can be used to easily stop

receiving notifications, like this:

token.Dispose ();

Or you can call

NSNotification.DefaultCenter.RemoveObserver

and pass the token. If your notification contains parameters, you

should specify a helper EventArgs interface, like this:

interface MyClass {

[Notification (typeof (MyScreenChangedEventArgs)]

[Field ("MyClassScreenChangedNotification")]

NSString ScreenChangedNotification { get; }

}

// The helper EventArgs declaration

interface MyScreenChangedEventArgs {

[Export ("ScreenXKey")]

nint ScreenX { get; set; }

[Export ("ScreenYKey")]

nint ScreenY { get; set; }

[Export ("DidGoOffKey")]

[ProbePresence]

bool DidGoOff { get; }

}

The above will generate a MyScreenChangedEventArgs class with the

ScreenX and ScreenY properties that will fetch the data from the

NSNotification.UserInfo

dictionary using the keys "ScreenXKey" and "ScreenYKey" respectively

and apply the proper conversions. The [ProbePresence] attribute is

used for the generator to probe if the key is set in the UserInfo,

instead of trying to extract the value. This is used for cases where

the presence of the key is the value (typically for boolean values).

This allows you to write code like this:

var token = MyClass.NotificationsObserveScreenChanged ((notification) => {

Console.WriteLine ("The new screen dimensions are {0},{1}", notification.ScreenX, notification.ScreenY);

});

Binding categories

Categories are an Objective-C mechanism used to extend the set of

methods and properties available in a class. In practice, they are

used to either extend the functionality of a base class (for example

NSObject) when a specific framework is linked in (for example UIKit),

making their methods available, but only if the new framework is

linked in. In some other cases, they are used to organize features

in a class by functionality. They are similar in spirit to C#

extension methods.This is what a category would look like in Objective-C:

@interface UIView (MyUIViewExtension)

-(void) makeBackgroundRed;

@end

The above example if found on a library would extend instances of

UIView with the method makeBackgroundRed.

To bind those, you can use the [Category]

attribute on an interface definition. When using the

[Category]

attribute, the meaning of the

[BaseType]

attribute changes from being used to specify the base class to extend, to

be the type to extend.

The following shows how the UIView extensions are bound and turned

into C# extension methods:

[BaseType (typeof (UIView))]

[Category]

interface MyUIViewExtension {

[Export ("makeBackgroundRed")]

void MakeBackgroundRed ();

}

The above will create a MyUIViewExtension a class that contains the

MakeBackgroundRed extension method. This means that you can now call

"MakeBackgroundRed" on any UIView subclass, giving you the same

functionality you would get on Objective-C. In some other cases,

categories are used not to extend a system class, but to organize

functionality, purely for decoration purposes. Like this:

@interface SocialNetworking (Twitter)

- (void) postToTwitter:(Message *) message;

@end

@interface SocialNetworking (Facebook)

- (void) postToFacebook:(Message *) message andPicture: (UIImage*)

picture;

@end

Although you can use the

[Category]

attribute also for this decoration style of declarations, you might as well

just add them all to the class definition. Both of these would achieve the

same:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface SocialNetworking {

}

[Category]

[BaseType (typeof (SocialNetworking))]

interface Twitter {

[Export ("postToTwitter:")]

void PostToTwitter (Message message);

}

[Category]

[BaseType (typeof (SocialNetworking))]

interface Facebook {

[Export ("postToFacebook:andPicture:")]

void PostToFacebook (Message message, UIImage picture);

}

It is just shorter in these cases to merge the categories:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface SocialNetworking {

[Export ("postToTwitter:")]

void PostToTwitter (Message message);

[Export ("postToFacebook:andPicture:")]

void PostToFacebook (Message message, UIImage picture);

}

Binding blocks

Blocks are a new construct introduced by Apple to bring the functional

equivalent of C# anonymous methods to Objective-C. For example, the

NSSet class now exposes this method:

- (void) enumerateObjectsUsingBlock:(void (^)(id obj, BOOL *stop) block

The above description declares a method called

enumerateObjectsUsingBlock: that takes one argument named

block. This block is similar to a C# anonymous method in that it has

support for capturing the current environment (the "this" pointer,

access to local variables and parameters). The above method in NSSet

invokes the block with two parameters an NSObject (the id obj part)

and a pointer to a boolean (the BOOL *stop) part.

To bind this kind of API with btouch, you need to first declare the block type signature as a C# delegate and then reference it from an API entry point, like this:

// This declares the callback signature for the block:

delegate void NSSetEnumerator (NSObject obj, ref bool stop)

// Later, inside your definition, do this:

[Export ("enumerateObjectUsingBlock:")]

void Enumerate (NSSetEnumerator enum)

And now your code can call your function from C#:

var myset = new NSMutableSet ();

myset.Add (new NSString ("Foo"));

s.Enumerate (delegate (NSObject obj, ref bool stop){

Console.WriteLine ("The first object is: {0} and stop is: {1}", obj, stop);

});

You can also use lambdas if you prefer:

var myset = new NSMutableSet ();

mySet.Add (new NSString ("Foo"));

s.Enumerate ((obj, stop) => {

Console.WriteLine ("The first object is: {0} and stop is: {1}", obj, stop);

});

Asynchronous methods

The binding generator can turn a certain class of methods into async-friendly methods (methods that return a Task or Task<T>).

You can use the

[Async]

attribute on methods that return

void and whose last argument is a callback. When you apply

this to a method, the binding generator will generate a

version of that method with the suffix Async. If the callback

takes no parameters, the return value will be a Task, if the

callback takes a parameter, the result will be a

Task<T>. If the callback takes multiple parameters, you

should set the ResultType or ResultTypeName to specify the

desired name of the generated type which will hold all the

properties.

Example:

[Export ("loadfile:completed:")]

[Async]

void LoadFile (string file, Action<string> completed);

The above code will generate both the LoadFile method, as well as:

[Export ("loadfile:completed:")]

Task<string> LoadFileAsync (string file);

Surfacing strong types for weak NSDictionary parameters

In many places in the Objective-C API, parameters are passed as

weakly-typed NSDictionary APIs with specific keys and values, but these are

error prone (you can pass invalid keys, and get no warnings; you can

pass invalid values, and get no warnings) and frustrating to use as

they require multiple trips to the documentation to lookup the

possible key names and values.

The solution is to provide a strongly-typed version that provides the strongly-typed version of the API and behind the scenes maps the various underlying keys and values.

So for example, if the Objective-C API accepted an NSDictionary and it

is documented as taking the key XyzVolumeKey which takes an

NSNumber with a volume value from 0.0 to 1.0 and a XyzCaptionKey that

takes a string, you would want your users to have a nice API that looks like this:

public class XyzOptions {

public nfloat? Volume { get; set; }

public string Caption { get; set; }

}

The Volume property is defined as nullable float, as the convention in

Objective-C does not require these dictionaries to have the value, so

there are scenarios where the value might not be set.

To do this, you need to do a few things:

- Create a strongly-typed class, that subclasses DictionaryContainer and provides the various getters and setters for each property.

- Declare overloads for the methods taking

NSDictionaryto take the new strongly-typed version.

You can create the strongly-typed class either manually, or use the generator to do the work for you. We first explore how to do this manually so you understand what is going on, and then the automatic approach.

You need to create a supporting file for this, it does not go into your contract API. This is what you would have to write to create your XyzOptions class:

public class XyzOptions : DictionaryContainer {

# if !COREBUILD

public XyzOptions () : base (new NSMutableDictionary ()) {}

public XyzOptions (NSDictionary dictionary) : base (dictionary){}

public nfloat? Volume {

get { return GetFloatValue (XyzOptionsKeys.VolumeKey); }

set { SetNumberValue (XyzOptionsKeys.VolumeKey, value); }

}

public string Caption {

get { return GetStringValue (XyzOptionsKeys.CaptionKey); }

set { SetStringValue (XyzOptionsKeys.CaptionKey, value); }

}

# endif

}

You then should provide a wrapper method that surfaces the high-level API, on top of the low-level API.

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface XyzPanel {

[Export ("playback:withOptions:")]

void Playback (string fileName, [NullAllowed] NSDictionary options);

[Wrap ("Playback (fileName, options?.Dictionary")]

void Playback (string fileName, XyzOptions options);

}

If your API does not need to be overwritten, you can safely hide the

NSDictionary-based API by using the

[Internal]

attribute.

As you can see, we use the

[Wrap]

attribute to surface a new API entry point, and we surface it using our

strongly-typed XyzOptions class. The wrapper method also allows for null

to be passed.

Now, one thing that we did not mention is where the XyzOptionsKeys

values came from. You would typically group the keys that an API

surfaces in a static class like XyzOptionsKeys, like this:

[Static]

class XyzOptionKeys {

[Field ("kXyzVolumeKey")]

NSString VolumeKey { get; }

[Field ("kXyzCaptionKey")]

NSString CaptionKey { get; }

}

Let us look at the automatic support for creating these strongly-typed dictionaries. This avoids plenty of the boilerplate, and you can define the dictionary directly in your API contract, instead of using an external file.

To create a strongly-typed dictionary, introduce an interface in your

API and decorate it with the

StrongDictionary

attribute. This tells the generator that it should create a class

with the same name as your interface that will derive from

DictionaryContainer and will provide strong typed accessors for it.

The [StrongDictionary]

attribute takes one parameter, which is the name

of the static class that contains your dictionary keys. Then each

property of the interface will become a strongly-typed accessor. By

default, the code will use the name of the property with the suffix

"Key" in the static class to create the accessor.

This means that creating your strongly-typed accessor no longer requires an external file, nor having to manually create getters and setters for every property, nor having to lookup the keys manually yourself.

This is what your entire binding would look like:

[Static]

class XyzOptionKeys {

[Field ("kXyzVolumeKey")]

NSString VolumeKey { get; }

[Field ("kXyzCaptionKey")]

NSString CaptionKey { get; }

}

[StrongDictionary ("XyzOptionKeys")]

interface XyzOptions {

nfloat Volume { get; set; }

string Caption { get; set; }

}

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface XyzPanel {

[Export ("playback:withOptions:")]

void Playback (string fileName, [NullAllowed] NSDictionary options);

[Wrap ("Playback (fileName, options?.Dictionary")]

void Playback (string fileName, XyzOptions options);

}

In case you need to reference in your XyzOption members a different

field (that is not the name of the property with the suffix Key),

you can decorate the property with an

[Export]

attribute with the name that you want to use.

Type mappings

This section covers how Objective-C types are mapped to C# types.

Simple types

The following table shows how you should map types from the Objective-C and CocoaTouch world to the Xamarin.iOS world:

| Objective-C type name | Xamarin.iOS Unified API type |

|---|---|

BOOL, GLboolean |

bool |

NSInteger |

nint |

NSUInteger |

nuint |

CFTimeInterval / NSTimeInterval |

double |

NSString (more on binding NSString) |

string |

char * |

string (see also: [PlainString]) |

CGRect |

CGRect |

CGPoint |

CGPoint |

CGSize |

CGSize |

CGFloat, GLfloat |

nfloat |

CoreFoundation types (CF*) |

CoreFoundation.CF* |

GLint |

nint |

GLfloat |

nfloat |

Foundation types (NS*) |

Foundation.NS* |

id |

Foundation.NSObject |

NSGlyph |

nint |

NSSize |

CGSize |

NSTextAlignment |

UITextAlignment |

SEL |

ObjCRuntime.Selector |

dispatch_queue_t |

CoreFoundation.DispatchQueue |

CFTimeInterval |

double |

CFIndex |

nint |

NSGlyph |

nuint |

Arrays

The Xamarin.iOS runtime automatically takes care of converting C#

arrays to NSArrays and doing the conversion back, so for example the

imaginary Objective-C method that returns an NSArray of UIViews:

// Get the peer views - untyped

- (NSArray *)getPeerViews ();

// Set the views for this container

- (void) setViews:(NSArray *) views

Is bound like this:

[Export ("getPeerViews")]

UIView [] GetPeerViews ();

[Export ("setViews:")]

void SetViews (UIView [] views);

The idea is to use a strongly-typed C# array as this will allow the IDE to provide proper code completion with the actual type without forcing the user to guess, or look up the documentation to find out the actual type of the objects contained in the array.

In cases where you can not track down the actual most derived type contained

in the array, you can use NSObject [] as the return value.

Selectors

Selectors appear on the Objective-C API as the special type

SEL. When binding a selector, you would map the type to

ObjCRuntime.Selector. Typically selectors are exposed in an

API with both an object, the target object, and a selector to invoke

in the target object. Providing both of these basically corresponds to

the C# delegate: something that encapsulates both the method to invoke

as well as the object to invoke the method in.

This is what the binding looks like:

interface Button {

[Export ("setTarget:selector:")]

void SetTarget (NSObject target, Selector sel);

}

And this is how the method would typically be used in an application:

class DialogPrint : UIViewController {

void HookPrintButton (Button b)

{

b.SetTarget (this, new Selector ("print"));

}

[Export ("print")]

void ThePrintMethod ()

{

// This does the printing

}

}

To make the binding nicer to C# developers, you typically will provide

a method that takes an NSAction parameter, which allows C# delegates

and lambdas to be used instead of the Target+Selector. To do this you

would typically hide the SetTarget method by flagging it with an

[Internal]

attribute and then you would expose a new helper method, like this:

// API.cs

interface Button {

[Export ("setTarget:selector:"), Internal]

void SetTarget (NSObject target, Selector sel);

}

// Extensions.cs

public partial class Button {

public void SetTarget (NSAction callback)

{

SetTarget (new NSActionDispatcher (callback), NSActionDispatcher.Selector);

}

}

So now your user code can be written like this:

class DialogPrint : UIViewController {

void HookPrintButton (Button b)

{

// First Style

b.SetTarget (ThePrintMethod);

// Lambda style

b.SetTarget (() => { /* print here */ });

}

void ThePrintMethod ()

{

// This does the printing

}

}

Strings

When you are binding a method that takes an NSString, you can replace

that with a C# string type, both on return types and parameters.

The only case when you might want to use an NSString directly is when

the string is used as a token. For more information about strings and

NSString, read the API Design on

NSString document.

In some rare cases, an API might expose a C-like string (char *)

instead of an Objective-C string (NSString *). In those cases, you can

annotate the parameter with the

[PlainString]

attribute.

out/ref parameters

Some APIs return values in their parameters, or pass parameters by reference.

Typically the signature looks like this:

- (void) someting:(int) foo withError:(NSError **) retError

- (void) someString:(NSObject **)byref

The first example shows a common Objective-C idiom to return error

codes, a pointer to an NSError pointer is passed, and upon return the

value is set. The second method shows how an Objective-C method

might take an object and modify its contents. This would be a pass

by reference, rather than a pure output value.

Your binding would look like this:

[Export ("something:withError:")]

void Something (nint foo, out NSError error);

[Export ("someString:")]

void SomeString (ref NSObject byref);

Memory management attributes

When you use the [Export]

attribute and you are passing data that will be retained by the called method,

you can specify the argument semantics by passing it as a second parameter,

for example:

[Export ("method", ArgumentSemantic.Retain)]

The above would flag the value as having the "Retain" semantics. The semantics available are:

- Assign

- Copy

- Retain

Style guidelines

Using [Internal]

You can use the

[Internal]

attribute to hide a method from the public API. You might want to do

this in cases where the exposed API is too low-level and you want to

provide a high-level implementation in a separate file based on this

method.

You can also use this when you run into limitations in the binding generator, for example some advanced scenarios might expose types that are not bound and you want to bind in your own way, and you want to wrap those types yourself in your own way.

Event handlers and callbacks

Objective-C classes typically broadcast notifications or request information by sending a message on a delegate class (Objective-C delegate).

This model, while fully supported and surfaced by Xamarin.iOS can sometimes be cumbersome. Xamarin.iOS exposes the C# event pattern and a method-callback system on the class that can be used in these situations. This allows code like this to run:

button.Clicked += delegate {

Console.WriteLine ("I was clicked");

};

The binding generator is capable of reducing the amount of typing required to map the Objective-C pattern into the C# pattern.

Starting with Xamarin.iOS 1.4 it will be possible to also instruct the generator to produce bindings for a specific Objective-C delegates and expose the delegate as C# events and properties on the host type.

There are two classes involved in this process, the host class which

will is the one that currently emits events and sends those into the

Delegate or WeakDelegate and the actual delegate class.

Considering the following setup:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface MyClass {

[Export ("delegate", ArgumentSemantic.Assign)][NullAllowed]

NSObject WeakDelegate { get; set; }

[Wrap ("WeakDelegate")][NullAllowed]

MyClassDelegate Delegate { get; set; }

}

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface MyClassDelegate {

[Export ("loaded:bytes:")]

void Loaded (MyClass sender, int bytes);

}

To wrap the class you must:

- In your host class, add to your

[BaseType]

declaration the type that is acting as its delegate and the C# name that you exposed. In our example above those aretypeof (MyClassDelegate)andWeakDelegaterespectively. - In your delegate class, on each method that has more than two parameters, you need to specify the type that you want to use for the automatically generated EventArgs class.

The binding generator is not limited to wrapping only a single event destination, it is possible that some Objective-C classes to emit messages to more than one delegate, so you will have to provide arrays to support this setup. Most setups will not need it, but the generator is ready to support those cases.

The resulting code will be:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject),

Delegates=new string [] {"WeakDelegate"},

Events=new Type [] { typeof (MyClassDelegate) })]

interface MyClass {

[Export ("delegate", ArgumentSemantic.Assign)][NullAllowed]

NSObject WeakDelegate { get; set; }

[Wrap ("WeakDelegate")][NullAllowed]

MyClassDelegate Delegate { get; set; }

}

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject))]

interface MyClassDelegate {

[Export ("loaded:bytes:"), EventArgs ("MyClassLoaded")]

void Loaded (MyClass sender, int bytes);

}

The EventArgs is used to specify the name of the EventArgs class to be

generated. You should use one per signature (in this example, the EventArgs will

contain a With property of type nint).

With the definitions above, the generator will produce the following event in the generated MyClass:

public MyClassLoadedEventArgs : EventArgs {

public MyClassLoadedEventArgs (nint bytes);

public nint Bytes { get; set; }

}

public event EventHandler<MyClassLoadedEventArgs> Loaded {

add; remove;

}

So you can now use the code like this:

MyClass c = new MyClass ();

c.Loaded += delegate (sender, args){

Console.WriteLine ("Loaded event with {0} bytes", args.Bytes);

};

Callbacks are just like event invocations, the difference is that

instead of having multiple potential subscribers (for example,

multiple methods can hook into a Clicked event or a DownloadFinished event)

callbacks can only have a single subscriber.

The process is identical, the only difference is that instead of

exposing the name of the EventArgs class that will be generated, the

EventArgs actually is used to name the resulting C# delegate name.

If the method in the delegate class returns a value, the binding

generator will map this into a delegate method in the parent class

instead of an event. In these cases you need to provide the default

value that should be returned by the method if the user does not hook

up to the delegate. You do this using the

[DefaultValue]

or [DefaultValueFromArgument]

attributes.

[DefaultValue]

will hardcode a return value, while

[DefaultValueFromArgument]

is used to specify which input argument will be returned.

Enumerations and base types

You can also reference enumerations or base types that are not directly supported by the btouch interface definition system. To do this, put your enumerations and core types into a separate file and include this as part of one of the extra files that you provide to btouch.

Linking the dependencies

If you are binding APIs that are not part of your application, you need to make sure that your executable is linked against these libraries.

You need to inform Xamarin.iOS how to link your libraries, this can be done

either by altering your build configuration to invoke the mtouch command with

some extra build arguments that specify how to link with the new libraries using

the "-gcc_flags" option, followed by a quoted string that contains all the extra

libraries that are required for your program, like this:

-gcc_flags "-L$(MSBuildProjectDirectory) -lMylibrary -force_load -lSystemLibrary -framework CFNetwork -ObjC"

The above example will link libMyLibrary.a, libSystemLibrary.dylib and

the CFNetwork framework library into your final executable.

Or you can take advantage of the assembly-level

[LinkWithAttribute],

that you can embed in your contract files (such as AssemblyInfo.cs).

When you use the [LinkWithAttribute],

you will need to have your native library available at the time you

make your binding, as this will embed the native library with your

application. For example:

// Specify only the library name as a constructor argument and specify everything else with properties:

[assembly: LinkWith ("libMyLibrary.a", LinkTarget = LinkTarget.ArmV6 | LinkTarget.ArmV7 | LinkTarget.Simulator, ForceLoad = true, IsCxx = true)]

// Or you can specify library name *and* link target as constructor arguments:

[assembly: LinkWith ("libMyLibrary.a", LinkTarget.ArmV6 | LinkTarget.ArmV7 | LinkTarget.Simulator, ForceLoad = true, IsCxx = true)]

You might be wondering, why do you need -force_load command, and the

reason is that the -ObjC flag although it compiles the code in, it

does not preserve the metadata required to support categories (the

linker/compiler dead code elimination strips it) which you need at

runtime for Xamarin.iOS.

Assisted references

Some transient objects like action sheets and alert boxes are cumbersome to keep track of for developers and the binding generator can help a little bit here.

For example if you had a class that showed a message and then

generated a Done event, the traditional way of handling this would

be:

class Demo {

MessageBox box;

void ShowError (string msg)

{

box = new MessageBox (msg);

box.Done += { box = null; ... };

}

}

In the above scenario the developer needs to keep the reference to the object themselves and either leak or actively clear the reference for box on their own. While binding code, the generator supports keeping track of the reference for you and clear it when a special method is invoked, the above code would then become:

class Demo {

void ShowError (string msg)

{

var box = new MessageBox (msg);

box.Done += { ... };

}

}

Notice how it is no longer necessary to keep the variable in an instance, that it works with a local variable and that it is not necessary to clear the reference when the object dies.

To take advantage of this, your class should have a Events property

set in the [BaseType]

declaration and also the KeepUntilRef variable set to the name of the

method that is invoked when the object has completed its work, like this:

[BaseType (typeof (NSObject), KeepUntilRef="Dismiss"), Delegates=new string [] { "WeakDelegate" }, Events=new Type [] { typeof (SomeDelegate) }) ]

class Demo {

[Export ("show")]

void Show (string message);

}

Inheriting protocols

As of Xamarin.iOS v3.2, we support inheriting from protocols that have

been marked with the [Model]

property. This is useful in certain API patterns, such as in MapKit where

the MKOverlay protocol, inherits from the MKAnnotation protocol, and is

adopted by a number of classes which inherit from NSObject.

Historically we required copying the protocol to every implementation,

but in these cases now we can have the MKShape class inherit from the

MKOverlay protocol and it will generate all the required methods

automatically.