Silicon assisted security

In addition to a modern hardware root-of-trust, there are multiple capabilities in the latest chips that harden the operating system against threats. These capabilities protect the boot process, safeguard the integrity of memory, isolate security-sensitive compute logic, and more.

Secured kernel

To secure the kernel, we have two key features: Virtualization-based security (VBS) and hypervisor-protected code integrity (HVCI). All Windows 11 devices support HVCI and come with VBS and HVCI protection turned on by default on most/all devices.

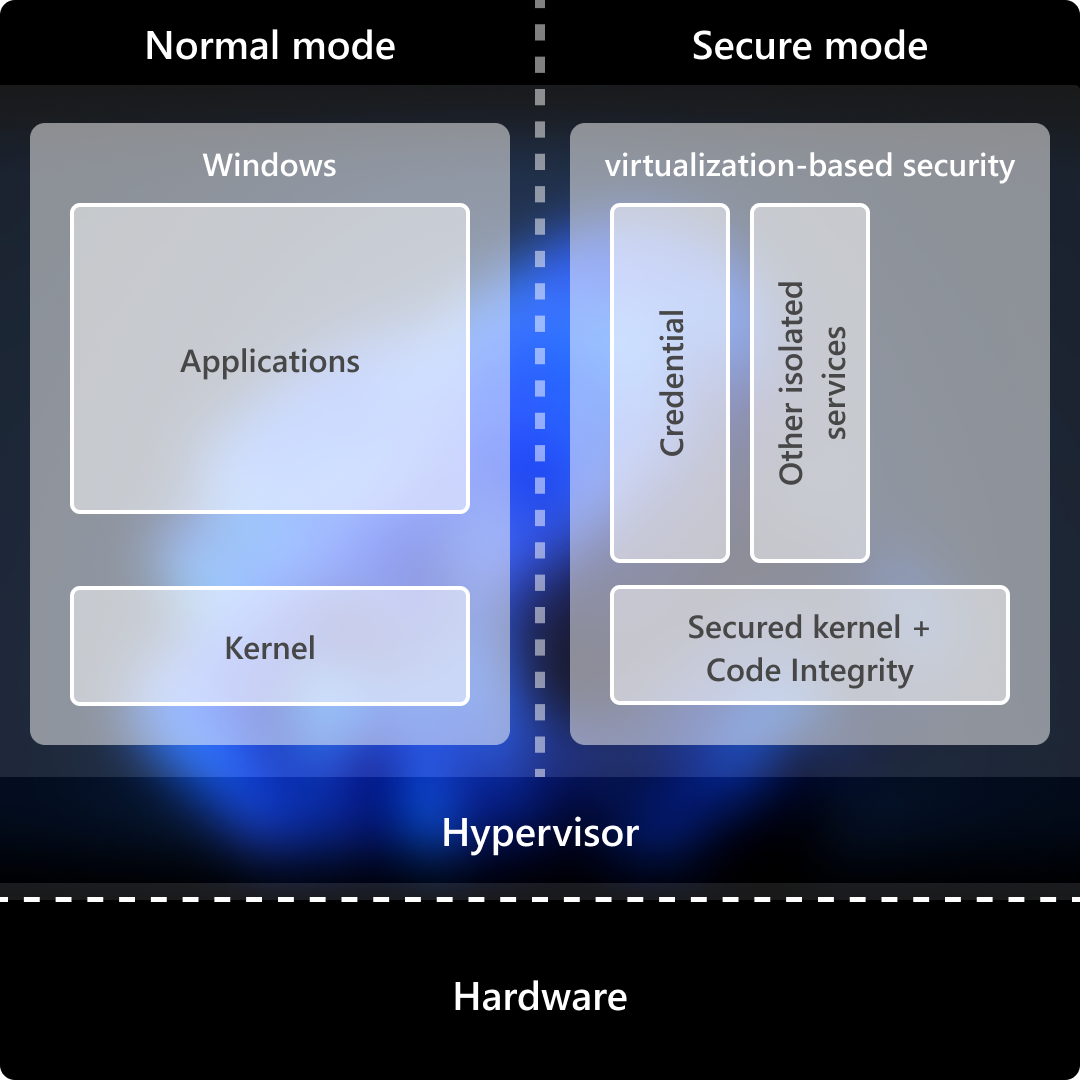

Virtualization-based security (VBS)

Virtualization-based security (VBS), also known as core isolation, is a critical building block in a secure system. VBS uses hardware virtualization features to host a secure kernel separated from the operating system. This means that even if the operating system is compromised, the secure kernel is still protected. The isolated VBS environment protects processes, such as security solutions and credential managers, from other processes running in memory. Even if malware gains access to the main OS kernel, the hypervisor and virtualization hardware help prevent the malware from executing unauthorized code or accessing platform secrets in the VBS environment. VBS implements virtual trust level 1 (VTL1), which has higher privilege than the virtual trust level 0 (VTL0) implemented in the main kernel.

Since more privileged virtual trust levels (VTLs) can enforce their own memory protections, higher VTLs can effectively protect areas of memory from lower VTLs. In practice, this allows a lower VTL to protect isolated memory regions by securing them with a higher VTL. For example, VTL0 could store a secret in VTL1, at which point only VTL1 could access it. Even if VTL0 is compromised, the secret would be safe.

Learn more

Hypervisor-protected code integrity (HVCI)

Hypervisor-protected code integrity (HVCI), also called memory integrity, uses VBS to run Kernel Mode Code Integrity (KMCI) inside the secure VBS environment instead of the main Windows kernel. This helps prevent attacks that attempt to modify kernel-mode code for things like drivers. The KMCI checks that all kernel code is properly signed and hasn't been tampered with before it's allowed to run. HVCI ensures that only validated code can be executed in kernel mode. The hypervisor uses processor virtualization extensions to enforce memory protections that prevent kernel-mode software from executing code that hasn't been first validated by the code integrity subsystem. HVCI protects against common attacks like WannaCry that rely on the ability to inject malicious code into the kernel. HVCI can prevent injection of malicious kernel-mode code even when drivers and other kernel-mode software have bugs.

With new installs of Windows 11, OS support for VBS and HVCI is turned on by default for all devices that meet prerequisites.

Learn more

Hypervisor-enforced Paging Translation (HVPT)

Hypervisor-enforced Paging Translation (HVPT)

Hypervisor-enforced Paging Translation (HVPT) is a security enhancement to enforce the integrity of guest virtual address to guest physical address translations. HVPT helps protect critical system data from write-what-where attacks where the attacker can write an arbitrary value to an arbitrary location often as the result of a buffer overflow. HVPT helps to protect page tables that configure critical system data structures.

Hardware-enforced stack protection

Hardware-enforced stack protection integrates software and hardware for a modern defense against cyberthreats like memory corruption and zero-day exploits. Based on Control-flow Enforcement Technology (CET) from Intel and AMD Shadow Stacks, hardware-enforced stack protection is designed to protect against exploit techniques that try to hijack return addresses on the stack.

Application code includes a program processing stack that hackers seek to corrupt or disrupt in a type of attack called stack smashing. When defenses like executable space protection began thwarting such attacks, hackers turned to new methods like return-oriented programming. Return-oriented programming, a form of advanced stack smashing, can bypass defenses, hijack the data stack, and ultimately force a device to perform harmful operations. To guard against these control-flow hijacking attacks, the Windows kernel creates a separate shadow stack for return addresses. Windows 11 extends stack protection capabilities to provide both user mode and kernel mode support.

Learn more

- Understanding Hardware-enforced Stack Protection

- Developer Guidance for hardware-enforced stack protection

Kernel direct memory access (DMA) protection

Windows 11 protects against physical threats such as drive-by direct memory access (DMA) attacks. Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) hot-pluggable devices, including Thunderbolt, USB4, and CFexpress, enable users to connect a wide variety of external peripherals to their PCs with the same plug-and-play convenience as USB. These devices encompass graphics cards and other PCI components. Since PCI hot-plug ports are external and easily accessible, PCs are susceptible to drive-by DMA attacks. Memory access protection (also known as Kernel DMA Protection) protects against these attacks by preventing external peripherals from gaining unauthorized access to memory. Drive-by DMA attacks typically happen quickly while the system owner isn't present. The attacks are performed using simple to moderate attacking tools created with affordable, off-the-shelf hardware and software that don't require the disassembly of the PC. For example, a PC owner might leave a device for a quick coffee break. Meanwhile, an attacker plugs an external tool into a port to steal information or inject code that gives the attacker remote control over the PCs, including the ability to bypass the lock screen. With memory access protection built in and enabled, Windows 11 is protected against physical attack wherever people work.

Learn more

Secured-core PC and Edge Secured-Core

The March 2021 Security Signals report found that more than 80% of enterprises have experienced at least one firmware attack in the past two years. For customers in data-sensitive industries like financial services, government, and healthcare, Microsoft has worked with OEM partners to offer a special category of devices called Secured-core PCs (SCPCs), and an equivalent category of embedded IoT devices called Edge Secured-Core (ESc). The devices ship with more security measures enabled at the firmware layer, or device core, that underpins Windows.

Secured-core PCs and edge devices help prevent malware attacks and minimize firmware vulnerabilities by launching into a clean and trusted state at startup with a hardware-enforced root-of-trust. Virtualization-based security comes enabled by default. Built-in hypervisor-protected code integrity (HVCI) shield system memory, ensuring that all kernel executable code is signed only by known and approved authorities. Secured-core PCs and edge devices also protect against physical threats such as drive-by direct memory access (DMA) attacks with kernel DMA protection.

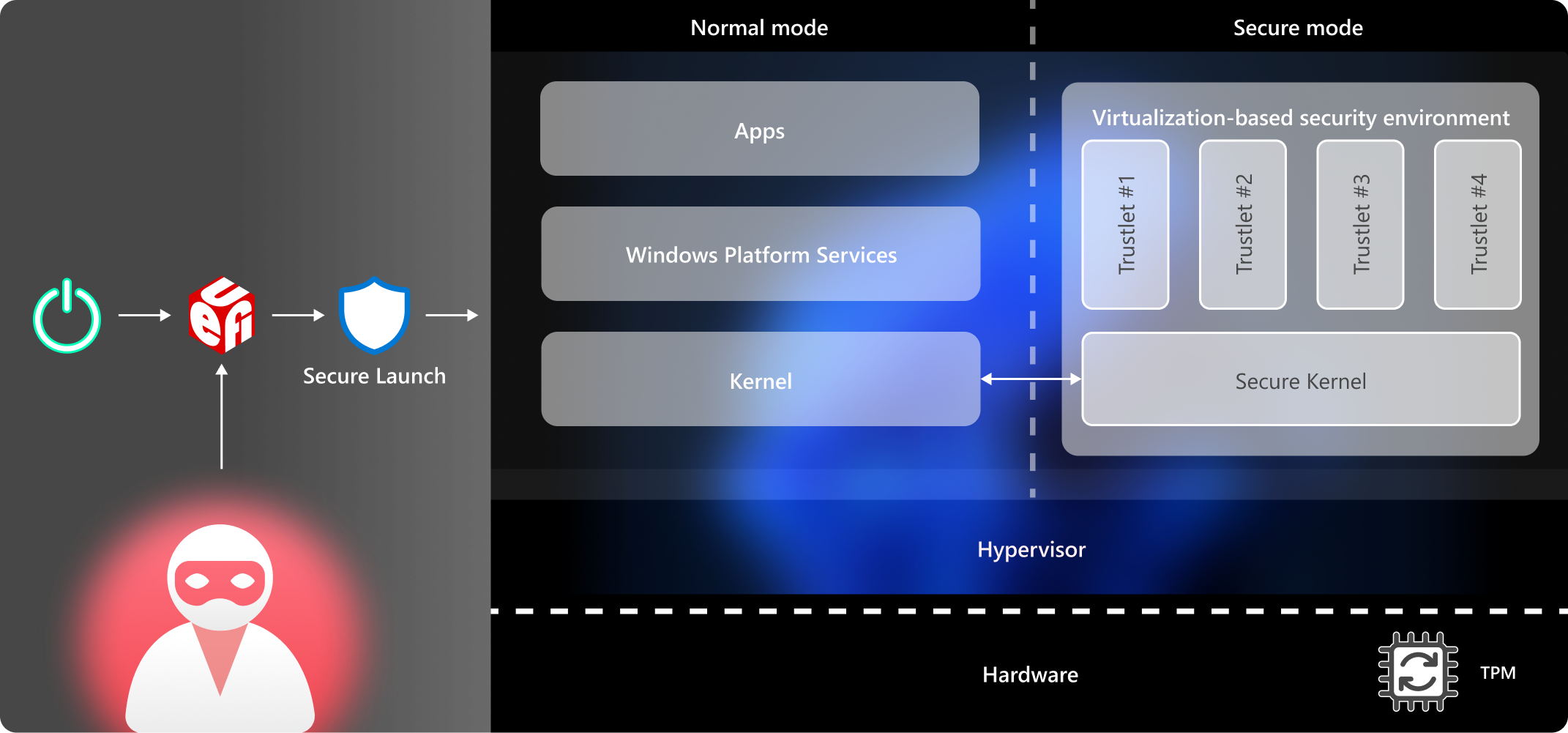

Secured-core PCs and edge devices provide multiple layers of robust protection against hardware and firmware attacks. Sophisticated malware attacks commonly attempt to install bootkits or rootkits on the system to evade detection and achieve persistence. This malicious software may run at the firmware level prior to Windows being loaded or during the Windows boot process itself, enabling the system to start with the highest level of privilege. Because critical subsystems in Windows use Virtualization-based security, protecting the hypervisor becomes increasingly important. To ensure that no unauthorized firmware or software can start before the Windows bootloader, Windows PCs rely on the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Secure Boot standard, a baseline security feature of all Windows 11 PCs. Secure Boot helps ensure that only authorized firmware and software with trusted digital signatures can execute. In addition, measurements of all boot components are securely stored in the TPM to help establish a nonrepudiable audit log of the boot called the Static Root of Trust for Measurement (SRTM).

Thousands of OEM vendors produce numerous device models with diverse UEFI firmware components, which in turn creates an incredibly large number of SRTM signatures and measurements at bootup. Because these signatures and measurements are inherently trusted by Secure Boot, it can be challenging to constrain trust to only what is needed to boot on any specific device. Traditionally, blocklists and allowlists were the two main techniques used to constrain trust, and they continue to expand if devices rely only on SRTM measurements.

Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM)

In secured-core PCs and edge devices, System Guard Secure Launch protects bootup with a technology known as the Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM). With DRTM, the system initially follows the normal UEFI Secure Boot process. However, before launching, the system enters a hardware-controlled trusted state that forces the CPU down a hardware-secured code path. If a malware rootkit or bootkit bypasses UEFI Secure Boot and resides in memory, DRTM prevents it from accessing secrets and critical code protected by the Virtualization-based security environment. Firmware Attack Surface Reduction (FASR) technology can be used instead of DRTM on supported devices, such as Microsoft Surface.

System Management Mode (SMM) isolation is an execution mode in x86-based processors that runs at a higher effective privilege than the hypervisor. SMM complements the protections provided by DRTM by helping to reduce the attack surface. Relying on capabilities provided by silicon providers like Intel and AMD, SMM isolation enforces policies that implement restrictions such as preventing SMM code from accessing OS memory. The SMM isolation policy is included as part of the DRTM measurements that can be sent to a verifier like Microsoft Azure Remote Attestation.

Learn more

- System Guard Secure Launch

- Firmware Attack Surface Reduction

- Windows 11 secured-core PCs

- Edge Secured-Core

Configuration lock

In many organizations, IT administrators enforce policies on their corporate devices to protect the OS and keep devices in a compliant state by preventing users from changing configurations and creating configuration drift. Configuration drift occurs when users with local admin rights change settings and put the device out of sync with security policies. Devices in a noncompliant state can be vulnerable until the next sync, when configuration is reset with the device management solution.

Configuration lock is a secured-core PC and edge device feature that prevents users from making unwanted changes to security settings. With configuration lock, Windows monitors supported registry keys and reverts to the IT-desired state in seconds after detecting a drift.

Learn more