Pushing the Limits of Windows: USER and GDI Objects – Part 1

So far in the Pushing the Limits of Windows series, I’ve focused on resources managed by the Windows operating system kernel, including physical and virtual memory, paged and nonpaged pool, processes, threads and handles. In this and the next post, however, I will explore two resources managed by the Windows window manager, USER and GDI objects, that represent window elements (like windows and menus) and graphics constructs (like pens, brushes and drawing surfaces). Just like for the other resources I’ve discussed in previous posts, exhausting the various USER and GDI resource limits can lead to unpredictable behavior, including application failures and an unusable system.

As always, I recommend you read the previous posts before this one, because some of the limits related to USER and GDI resources are based on limits I’ve covered. Here’s a full index of my other Pushing the Limits of Windows posts:

Pushing the Limits of Windows: Physical Memory

Pushing the Limits of Windows: Virtual Memory

Pushing the Limits of Windows: Paged and Nonpaged Pool

Sessions, Window Stations and Desktops

There are a few concepts that make the relationship between USER objects, GDI objects, and the system more clear. The first is the session. A session represents an interactive user logon that has its own keyboard, mouse and display and represents both a security and resource boundary.

The session concept was first introduced with Terminal Services (now called Remote Desktop Services) in Windows NT 4 Terminal Server Edition, where the physical display, keyboard and mouse concepts were virtualized for each user interactively logging on to a system remotely, and core Terminal Services functionality was built into Windows 2000 Server. In Windows XP, sessions were leveraged to create the Fast User Switching (FUS) feature that allows you to switch between multiple interactive logins on the same physical display, keyboard and mouse.

Thus, a session can be connected with the physical display and input devices attached to the system, connected with a logical display and input devices like ones presented by a Remote Desktop client application, or be in a disconnected state like exists when you switch away from a session with Fast User Switching or terminate a Remote Desktop Client connection without logging off the session.

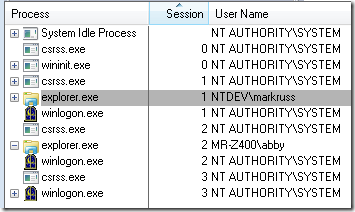

Every process is uniquely associated with a specific session, which you can see when you add the Session column to Sysinternals Process Explorer. This screenshot, in which I’ve collapsed the process tree to show only processes that have no parent, is from a Remote Desktop Services (RDS – formerly Terminal Server Services) system that has four active sessions: session 0 is the dedicated session in which system processes execute on Windows Vista and higher; session 1 is the session in which I’m writing this post; Session 2 is the session of another user account that I’m concurrently logged into from another system; and finally, session 3 is one that Remote Desktop Services proactively created to be ready for the next interactive logon:

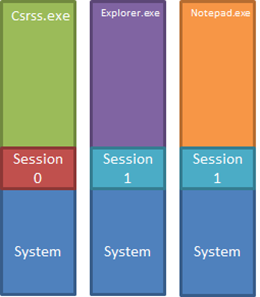

Since every process is associated with a specific session and the operating system usually only needs access to the session-specific data of the current process’s session, Windows defines a view into a process’s session data in the process’s virtual address space. Thus, when the system switches between threads of different processes, it also switches address spaces, switching the current session view. When the Csrss.exe process of Session 0 is the current process, for example, the address space mappings include the system address space (which is included in every process’s address space), Csrss’s address space, and the Session 0 address space. The region of memory mapping a session’s data is known as Session View Space or Session Space. When the system switches to a thread from Session 1’s Explorer process, the mappings change accordingly, and when it switches to a thread from Notepad, the Session 1 Session Space remains mapped:

Note that the figure isn’t exactly correct for 32-bit Windows Vista and higher, since dynamic system address space means that the Session Space isn’t necessarily contiguous and can grow and shrink as required on those systems.

The next concept is the desktop, an object defined by the window manager to represent a virtual display that includes the windows associated with the desktop (note that this is different than Explorer’s definition of a desktop, which is the user’s directory with shortcuts and other objects the user places there). The default desktop is named “Default”, but applications can create additional desktops and switch the connection to the logical display, something the Sysinternals Desktops utility uses to create up to four virtual desktops a user can switch between.

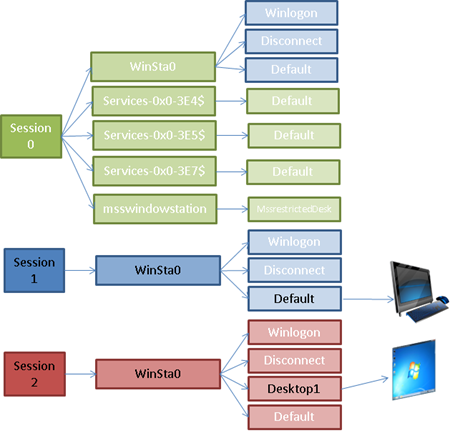

Finally, to support multiple virtual displays that are associated with the same window manager instance, the window manager defines the window station object. A window station is associated with a particular session and a session can have multiple window stations, but each session has only one interactive window station, called Winsta0, that can connect with a physical or logical display, keyboard and mouse; the other window stations are essentially “headless” and support for them exists solely to isolate processes that expect window manager services, but that shouldn’t. For example, the system creates non-interactive window stations for each service account with which it associates processes running in the account, since Windows services should not display user-interfaces.

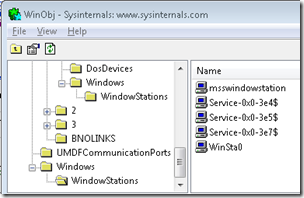

You can see the window stations associated with Session 0 by looking in the Object Manager namespace under the \Windows directory using the Sysinternals Winobj tool (viewing the directory requires running elevated with administrative privileges). Here you can see that a window station the Microsoft Windows Search Service creates to run search filters in, window stations for each of the three built-in service accounts (System, Network Service and Local Service), and Session 0’s interactive window station:

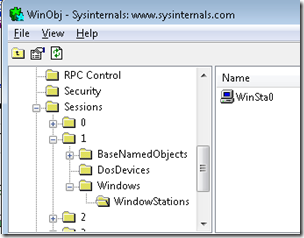

You can see the window stations associated with other sessions in the Sessions directory in the Object Manager namespace. Here’s the only window station, the interactive WinSta0 window station, associated with my logon session:

This diagram shows the relationship between sessions, window stations, and desktops for a system that has one user logged into Session1 on the physical console and another logged on to Session 2 via a remote desktop connection where the user has run a virtual desktops utility and switched the display to Desktop1.

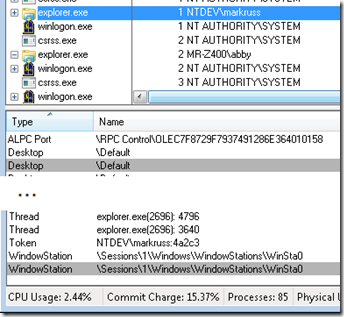

Besides having an association with a particular session, processes are associated with a specific window station and desktop, though processes can switch between both and threads can switch between desktops. Thus, every process’s association can be represented with a hierarchical path like this: “Session 1\WinSta0\Default”. You can in most cases indirectly determine what window station and desktop a process is connected to by looking at its handle table in Process Explorer’s handle view to see the names of the objects it has open. This screen shots of the handle table of an Explorer process show that it is connected to the Default desktop on WinSta0 of Session 1:

User Objects

With the fundamental concepts in hand, let’s turn our attention first to USER objects. USER objects get their name from the fact that they represent user interface elements like desktops, windows, menus, cursors, icons, and accelerator tables (menu keyboard shortcuts). Despite the fact that USER objects are associated with a specific desktop, they must be accessible from all the desktops of a session, for example to allow a process on one desktop to register for a hotkey that can be entered on any of them. For that reason, the window manager assigns USER object identifiers that are scoped to a window station.

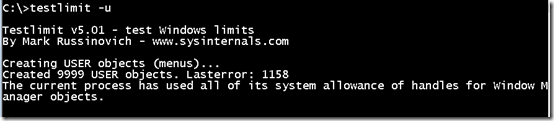

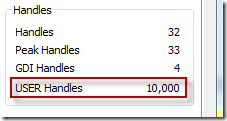

A basic limitation imposed by the window manager is that no process can create more than 10,000 USER objects. That limitation attempts to prevent a single process from exhausting the resources associated with USER objects, either because it’s programmed with algorithms that can create excessive number of objects or because it leaks objects by allocating them and not deleting them when it’s through using them. You can easily verify this limit by running the Sysinternals Testlimit utility with the –u switch, which directs Testlimit to create as many USER objects as it can:

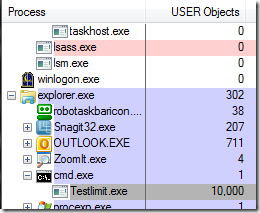

The window manager keeps track of how many USER objects a process allocates, which you can see when you add the USER Objects column to Process Explorer’s display, so that you can keep tabs on the number of objects processes allocate. This screenshot shows that, as expected, Windows system processes, including Lsass.exe (the Local Security Authority Subsystem) and service processes like Svchost, don’t allocate USER objects because they have no user interface:

Process Explorer shows the number of USER objects a process has allocated on the Performance page of a process’s process properties dialog:

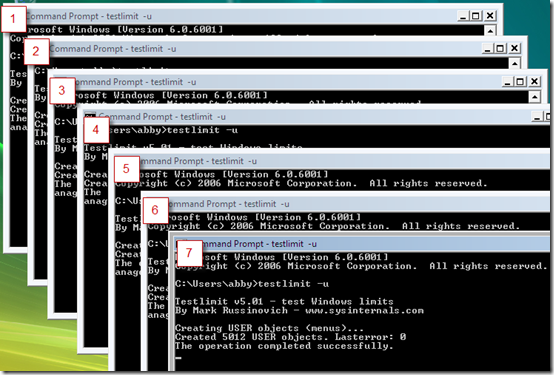

One fundamental limitation on the number of USER objects comes from the fact that their identifiers were 16-bit values in the first versions of Windows, which were 16-bit. When 32-bit support was added in later versions, USER identifiers had to remain restricted to 16-bit values so that 16-bit processes could interact with windows and other USER objects created by 32-bit processes. Thus, 65,535 (2^16) is the limit on the total number of USER objects that can be created on a session (and for historical reasons, windows must have even-numbered identifiers, so there can be a maximum of 32,768 windows per session). You can verify this limit by running multiple copies of Testlimit with the –u switch until you can’t create any more. Assuming the processes you already have running aren’t using an excessive number of objects, you should be able to run 7 copies, where the first 6 allocate 10,000 objects and the last allocates the difference between the number of already allocated objects and 65,535:

Be sure that you’re prepared to hard power-off your system when you do this because the desktop may become unusable. Many operations, like even opening the start menu’s shutdown menu, require USER objects, and when no more can be allocated the system will behave in bizarre ways. I wasn’t even able to terminate a Notepad process I had running by clicking on its close menu button after USER objects had been exhausted.

So far I’ve talked only about the limits associated with absolute number of USER objects a process or window station can allocate, but there are other limits caused by the storage used for the USER objects themselves. Each desktop has its own region of memory, called the desktop heap, from which most USER objects created on the desktop are allocated. Because desktop heaps are stored in Session Space and 32-bit address spaces limit the amount of kernel-mode address space, the sizes of desktop heaps are capped at a relatively modest amount. They also vary in size depending on the type of desktop they are for and whether the system is a 32-bit or 64-bit system.

Matthew Justice’s Desktop Heap Overview and Desktop Heap, Part 2 articles from the NT Debugging Blog do an excellent job of documenting desktop heap sizes up through Windows Vista SP1. This table summarizes the sizes across Windows versions up through Windows Server 2008 R2:

| Interactive Desktop | Non-Interactive Desktop | Winlogon Desktop | Disconnect Desktop | |

| Windows XP 32-bit | 3 MB | 512 KB | 128 KB | 64 KB |

| Windows Server 2003 32-bit | 3 MB | 512 KB | 128 KB | 64 KB |

| Windows Server 2003 64-bit | 20 MB | 768 KB | 192 KB | 96 KB |

| Windows Vista/Windows Server 2008 32-bit | 12 MB | 512 KB | 128 KB | 64 KB |

| Windows Vista/Windows Server 2008 64-bit | 20 MB | 768 KB | 192 KB | 96 KB |

| Windows 7 32-bit | 12 MB | 512 KB | 128 KB | 64 KB |

| Windows 7/Windows Server 2008 R2 64-bit | 20 MB | 768 KB | 192 KB | 96 KB |

It’s worth noting that the original release of Windows Vista 32-bit had the 3 MB Interactive Heap size that previous 32-bit versions of Windows had. After the release our telemetry showed us that some users occasionally ran out of heap, presumably because they were running more applications on systems that had more memory, so SP1 raised the size to 12 MB. It’s also possible to override the default desktop heap sizes with registry settings described in Matthew’s article.

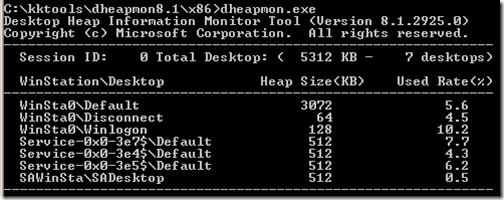

On versions of Windows prior to Windows Vista, you can use the Microsoft Desktop Heap Monitor tool to view the sizes of the Desktop Heaps and how much of each is in use. Here’s the output of the tool on a 32-bit Windows XP system showing that only 5.6% of heap (172 KB) on the interactive desktop, Default, has been consumed:

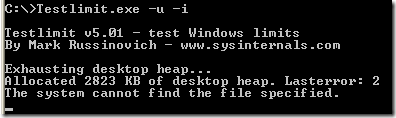

The tool hasn’t been updated for Windows Vista because the larger desktop heap sizes on newer versions of Windows mean that desktop heap is rarely exhausted before other USER object limits are hit. However, you can use Testlimit with the –u and –i switches to see how the system behaves when interactive desktop heap exhaustion occurs. The switch combination has Testlimit create window class data structures that have 4 KB of extra class storage until it fails. Here’s the output of Testlimit when run immediately after I captured the above Desktop Heap Monitor output. 2823 KB plus the 172 KB that Desktop Heap Monitor said was already allocated equals about 3 MB:

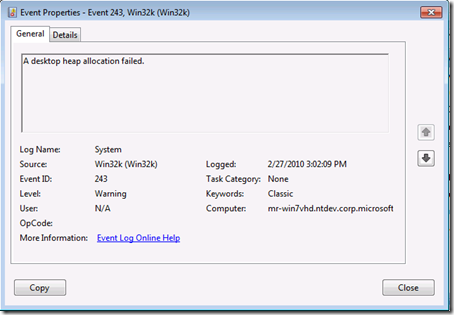

Though there’s no way to determine how much heap is in use on newer systems, the window manager writes an event to the system event log when there’s heap exhaustion that can help troubleshoot window manager issues:

That covers USER object limits. Stay tuned for Part 2, where I’ll discuss the limits related to window manager GDI objects.

Comments

Anonymous

January 01, 2003

Hi everybody, Marc, thanks for a great article. I did some tests on my Vista SP2 32-bit First I increased the second parameter of the SharedSection registry value from 12288 KB to 122880 KB. I read that Vista is using dynamic Session Space so that I left that value untouched. Then I ran testlimit -u -i and it used 65MB, so I guess that is the limit for a desktop? Why didn't it use the limit defined by the sharedsection i.e. 122MB? Thanks, DanielAnonymous

January 01, 2003

@tobi There are many ways an unprivileged user can perform a denial of service attack on their own session or even on a full windows system. This isn't considered a security issue. @Blake Coverett Yes, I'm positive. My Desktops uses the SwitchDesktop function to do exactly this on it's main window thread.Anonymous

January 01, 2003

@Blake Sorry, I misunderstood you. You're right that a thread cannot switch desktops after it has created a window or hook on a desktop, as documented here: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms686250(VS.85).aspx. That does not prevent them from switching desktops otherwise, however, which Desktops also depends on.Anonymous

January 01, 2003

Good catch, I've fixed the table.Anonymous

January 01, 2003

@katayamma 16-bit apps still run on 32-bit Windows. Further, usage typically doesn't come anywhere close to the limit so there's been no need to raise it.Anonymous

January 01, 2003

I'm unclear about something. The 64K object limit is something for 32bit OSs or does it also apply to 64bit versions? Why are we limited to 16bit object count when Windows has been using 32/64 bit for sometime now? Just curious. ThxAnonymous

March 03, 2010

according to wikipedia, there is no 32-bit version of 2008 r2, but your heap size table mentions it.Anonymous

March 04, 2010

Awesome article, Mark! This is the kind of stuff those of us who push Windows to its limits, really live for. Interestingly, in Windows 2000 with a custom set 8192KB Desktop Heap size, Windows chokes (serious window malfunctions, app crashes, can't create new Windows/dialogs) around 38-41% Used Rate via dheapmon. I've experienced this same boundary for the past 2-3 years since the Desktop Heap article from NTDebugging first enlightened me to the custom Desktop Heap settings (which were crucial in allowing me to run more apps simultaneously.) Why doesn't exhaustion happen at "100%"? I run into the limits pretty often (every few weeks) due to the large amount of apps I leave open, and I'd love to find more headroom.Anonymous

March 04, 2010

You might want to make a statement about the security implications of exhausting resources. As far as I understood it, you can only exhaust resources inside your own session, therefore no security bug is present.Anonymous

March 10, 2010

"Besides having an association with a particular session, processes are associated with a specific window station and desktop, though processes can switch between both and threads can switch between desktops." Are you positive about this? Perhaps things have changed, but my recollection from the NT 3.x days are that processes are associated with windowstations, threads are associated with desktops, and that once any call has been made into the window manager those associations are fixed. In particular, that you want to use them, you have to call SetProcessWindowStation or SetThreadDesktop before touching anything else in USER32. WindowStations, in keeping their own global atoms and clipboards were a bit of a vestigle attempt at what sessions became.Anonymous

March 14, 2010

SwitchDesktop is an entirely different matter, it changes the system's current input desktop, not the thread's desktop. I agree any thread can call SwitchDesktop, assuming the HDESK was opened with the the right attributes. The question was whether a thread could call SetThreadDesktop after it had already been assigned to a desktop by the window manager. I wrote some test code just now and it confirmed my recollection. If a thread has ever created a window on one desktop, even if that window has since been destroyed, it will never be allowed to SetThreadDesktop() to a different desktop and create windows there. I believe the same pattern also occurs with a process trying to change its windowstation, i.e. once any thread has been assigned a desktop, the process is locked to that desktop's windowstation. (But I haven't written that test code.) The test code can be found at http://www.bcdev.com/files/DesktopTest.cppAnonymous

March 14, 2010

So in cases where the XP registry cannot be modified to increase the desktop heap size (for whatever reason), can the Wininternals Desktop utility be used to get around the default 3 MB limit, IOW does each interactive desktop have its own 3 MB limit? Also a piece of feedback I would provide is that while the Event Log entry that newer versions of Windows provide in the case of heap exhaustion is useful, it would be even more useful if it contained more details on the problem, ie the process that tried the allocation, the size of the heap, etc.Anonymous

March 16, 2010

The MSDN docs assert a thread can't change its desktop while it has a current window or hook. The doc-bug/gotcha is that it can't change its desktop if it previously had a windows or hook either. Clearly there's a bad overload of the term 'switch' here, since SwitchDesktop does something completely unrelated to SetThreadDesktop.Anonymous

March 26, 2010

Thanks Mark - I am looking forward to the next article in this series. As a sysadmin I have run into desktop heap issues and the occasional USER objects shortage, and the fix has always been 'follow this arcane recipe without understanding the foundational concepts.' So I'm glad you're building reference articles like this!Anonymous

April 03, 2010

You might want to make a statement about the security implications of exhausting resources. As far as I understood it, you can only exhaust resources inside your own session, therefore no security bug is present.Anonymous

April 17, 2010

"Microsoft Desktop Heap Monitor... hasn’t been updated for Windows Vista" I wrote an updated driver so it could work on Vista, 2k8 and 7 last year. Its usefulness may have diminished with the larger heaps but if nothing else, it lets those who like numbers put some figures on usage. http://aw.comyr.com/2009/10/desktop-heap-monitor-vista-7/Anonymous

July 05, 2010

I appreciate you technical knowledge. One statement you made seemed a little too "public relations" oriented. You said "... After the release our telemetry showed us that some users occasionally ran out of heap..." The running out of heap had been a widely documented occurrence since the release of Windows XP, and the fix of increasing the Desktop Heap Limit in the SharedSection part of the SubSystems key had been documented on the internet for a long time, both on Microsoft sites and third-party sites. I'm not a Microsoft basher in any way, but I do believe in representing things fairly, and I think a much fairer statement might be something along the lines of: "Given that the problems of exhaustion of a 3 MB Interactive heap were widely know at the time, its hard to explain why Windows Vista 32-bit still had the 3 MB Interactive Heap limitation set when it was first released." I don't know if heap exhaustion was worse in Windows Vista, but it certainly impacted enough people in Windows XP that it should have been fixed prior to Vista's release.Anonymous

July 19, 2010

I am still waiting to hear about GDI objects. I see user handles but nothing on GDI's what gives?Anonymous

July 22, 2010

Hi Mark, I have some questions:

- Do you have the source for the TestLimit app? I'm curious how you're creating the USER Objects.

- I'm surprised to see that the Handle Count in TaskMgr was only 22 but the USER Objects was 10,000. I thought that the Handles included USER Objects along with Kernel objects. I have found the defn of the USER Objects on MSDN but I can't find any decent description on what "Handles" are.

- How would the "out of handle" error manifest itself in a .NET app? I can create one for testing if I know how you're creating the USER Objects. Dave

Anonymous

September 04, 2010

Hi Mark, thanks for writing this up. By the way, a direct link to the second part would have been really convenient! Blog series are too often only linked in the backward direction: only the last of the series has the entire contents...Anonymous

October 05, 2010

Hi Marks, thanks a lot for the explanations. A remark that the limit for the User objects can be relaxed by a registry key would have been helpful. We ran into a symptom with Windows 2008, that some of your classes now require twice as much user objects as it were the case with Windows 2003. We didn't notice that until we migrated a huge customer installation were we hit the limit. We now temporarily fixed it by raising the limit until we implement a better solution.