Fun with floating point

Introduction

WPF uses double-precision floating point numbers (double in C#) in much of its public API and it uses single-precision floating point for much of its internal rendering. So floating point math is something we deal with constantly. Oddly enough, I actually knew very little about the gory details until I recently tried to write a container that had to use doubles as a key, which required working around the problems with precision in floating point math. I found the whole exercise to be very interesting, and so I’ll present what I learned here.

The Problem

Consider this code:

if (0.8 - 0.7 == 0.1) { Console.WriteLine("Math makes sense."); }

Believe it or not, the comparison will fail. This bothers me, because I don’t know how to write code that will work as expected. (In this simple case, the compiler will actually generate a warning the the code in unreachable.)

Binging around the internet, I found a great article, which I recommend as a good read:

www.cygnus-software.com/papers/comparingfloats/comparingfloats.htm

A common approach is to never compare floating point numbers directly, but instead just check that the absolute value of the difference is small enough. The rub, of course, is that it is very hard to pick the right value for “small enough”. Especially since floating point numbers cover a huge range – from very, very small to very, very large. For example, +/- 0.0001 is probably fine for some values, but is probably not great for very, very large numbers and is certainly a bad choice for very, very small numbers where this tolerance is actually larger than the numbers being worked with.

Another idea is to scale the tolerance with the size of the floating point number. Basically, this technique uses a tolerance that is a percentage of the value. This seems like a reasonable idea to me, though might be difficult to implement efficiently.

Another idea is to consider equal two doubles who only differ in the least-significant bits of their significands, which is the premise of the article above.

No matter what you do, something to keep in mind is the requirements of the .Net Framework around equality and hashcodes. You need to ensure that anything that compares as equal will generate the same hashcode. Failing to do so will lead to subtle errors, such as loosing data in a hashtable.

Before designing a solution, let’s dig into the details of the floating point format.

Background

First, read the wikipedia article on the IEEE 754-2008 standard. The two formats we care most about are binary64 (double in C#) and binary32 (float in C#). Of course, the principles of the IEEE standard can be applied to other sizes, such as the fun Minifloat formats.

Today, we normally represent numbers in decimal positional notation. For example, the number 12.34. Each digit can be understood to be multiplied by some power (indicated by the position of the digit) of the base of the number system. Again, using decimal (base 10), we can expand this shorthand representation to be:

![clip_image002[22] clip_image002[22]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B22%5D_thumb.gif) Exponential notation can be used as a more compact representation of either very large or very small numbers. For instance, the number 1,234,000,000,000 could be written a number of ways using exponential notation:

Exponential notation can be used as a more compact representation of either very large or very small numbers. For instance, the number 1,234,000,000,000 could be written a number of ways using exponential notation:

This last form is known as normalized exponential notation, and there is a unique representation of every number in this notation. Which helps a lot when we try to represent numbers in computers.

The magnitude of the number is determined by the exponent, and the precision of the number is determined by the coefficient, otherwise know as the significand.

Base 10 is easy, how about Base 2

Of interest to us, of course, is base 2, since that is what computers use in their normal binary representation of data. The same principles apply: namely that each digit (0 or 1) is multiplied by some power (indicated by the position of the digit) of the base of the number system (2). So our original example of 12.25 (base 10) can be written as:

A fascinating observation, and one that is exploited in the binary IEEE 754 formats, is that in base 2 normalized exponential notation, the leading digit is always 1. You will see how this comes in handy in the next section.

Binary Representation

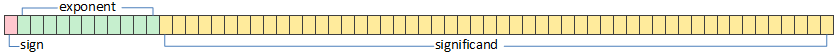

As stated in the introduction, the IEEE 754-2008 standard defines a number of binary formats. For now we will consider binary64 (double in C#). As the name suggests, this binary format is 64-bits wide, and allocates the bits as follows:

Sign: 1 bit

Exponent: 11 bits

Significand: 52 bits

A picture always helps:

The sign bit is simple enough: 0 for positive, 1 for negative. It is important to note that this is different way of encoding negative numbers than the more typical “two’s complement” technique. There are, for example, both a positive and a negative zero.

The exponent is a little more complicated. Being 11 bits, it can encode values between 0 and 2047, inclusive. (Note that 0 and 2047 both have special meanings, and are not used as exponents.) The exponent field needs to store both positive and negative values (for very small and very large numbers). Instead of storing a sign bit, the IEEE 754 standard specifies an exponent bias of 1023. Before storing a desired exponent value, you add 1023 and store the result. When reading the exponent field, you subtract 1023 to get the originally intended value. The result is that the exponent can effectively be between –1022 and 1023, inclusive.

As mentioned before, both 0 and 2047 (0x7FF) are special values for the exponent field. A value of 0 indicates that the number is subnormal. Previously we noted that a normalized exponential notation required that there be one non-zero digit before the decimal point, and the rest of the digits after the decimal point – and the whole thing multiplied by the base raised to some exponent. We also noted that in binary, the digit before the decimal point would always be 1. There are two cases that break this rule:

- ZeroA pure zero obviously cannot have a non-zero digit!

- Really, really small numbersBecause of the limited range of exponents, numbers even smaller than 1 * 2^-1022 cannot be represented with a leading digit of 1.

For these cases, the exponent field contains 0. The actual exponent value considered to be –1022 (as if the field contained 1), and the number is assumed to have a leading 0 before the decimal, which means that technically the number is no longer in normalized exponential notation. However, the representation is still unique because there is no other way to represent these really, really small numbers given the limits of the exponent field.

The other special value in the exponent field is 2047 (0x7FF). When the exponent field contains this value, the number is either NaN (Not A Number) or Infinity. If the significand is 0, then the number is considered to be Infinity. If the significant is non-zero, then the number is considered to be NaN. A couple of immediate observations: Infinity can be either positive or negative, and is basically one value larger than the maximum non-infinite value (or one value less than the minimum negative non-infinite value). There can be many different NaN values – all of the different possible significand values – and this is sometimes used to carry extra information. The sign bit can be set of cleared for a NaN, it is simply ignored. Supposedly NaNs can be either quiet or signalling, but the actual format is unclear (at least to me).

Representable Values

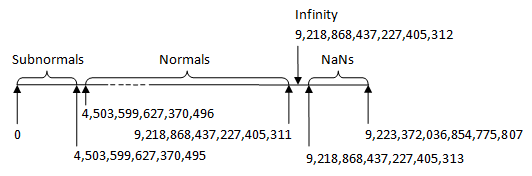

Since a double is 64-bits, we know that there are a finite number of values that can be represented. Counting all representable values – NaNs, Infinities, positive and negative, subnormals, normals, etc – is a simple calculation: 264 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,616.

Now that is a lot of numbers! Visualizing the representation of floating point numbers (not the floating point values) as a signed 64-bit number helps reinforce the intuition behind the format:

Note that the diagram is not to scale. By that I mean that the vast majority of representable numbers are in the range of Normals. The Subnormals and the NaNs account for a very small fraction of the representable values. I try to indicate this with the dashed line.

This diagram only shows the positive half. The negative half is exactly the same, with all of the numerical values being negative. Note that there are both a postitive and a negative 0, and there are both a positive and a negative infinity. While there are technically both positive and negative NaNs, the sign is ignored.

Distribution of floating point values

Now that we’ve seen how the representation are distributed between 0, subnormals, normals, infinity, and NaNs, let’s see how the actual floating point values are distributed. A 64-bit double contains way too many values to reason about, so I will take the liberty of switching to a simplified minifloat format. I’ve chosen a 6-bit format: 1 sign bit, 3 exponent bits, and 2 significand bits (but remember, we also have an implicit significand bit), and an exponent bias of 2. In excel I created the following table:

S |

E2 |

E1 |

E0 |

S0 |

S1 |

S2 |

Exponent |

Significand |

As Integer |

Value |

Classification |

|||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1.75 | -31 | -56.000 | NaN | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1.50 | -30 | -48.000 | NaN | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1.25 | -29 | -40.000 | NaN | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.00 | -28 | -32.000 | -Infinity | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1.75 | -27 | -28.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1.50 | -26 | -24.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1.25 | -25 | -20.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.00 | -24 | -16.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.75 | -23 | -14.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1.50 | -22 | -12.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1.25 | -21 | -10.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.00 | -20 | -8.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.75 | -19 | -7.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.50 | -18 | -6.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.25 | -17 | -5.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.00 | -16 | -4.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.75 | -15 | -3.500 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.50 | -14 | -3.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 | -13 | -2.500 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.00 | -12 | -2.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1.75 | -11 | -1.750 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.50 | -10 | -1.500 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.25 | -9 | -1.250 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | -8 | -1.000 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1.75 | -7 | -.875 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1.50 | -6 | -.750 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 1.25 | -5 | -.625 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 1.00 | -4 | -.500 | -Normal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0.75 | -3 | -.375 | -Subnormal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0.50 | -2 | -.250 | -Subnormal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0.25 | -1 | -.125 | -Subnormal | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0.00 | 0 | .000 | -0 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0.00 | 0 | .000 | +0 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0.25 | 1 | .125 | +Subnormal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0.50 | 2 | .250 | +Subnormal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0.75 | 3 | .375 | +Subnormal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 1.00 | 4 | .500 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 1.25 | 5 | .625 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1.50 | 6 | .750 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1.75 | 7 | .875 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 8 | 1.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.25 | 9 | 1.250 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.50 | 10 | 1.500 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1.75 | 11 | 1.750 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.00 | 12 | 2.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.25 | 13 | 2.500 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.50 | 14 | 3.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.75 | 15 | 3.500 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.00 | 16 | 4.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.25 | 17 | 5.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.50 | 18 | 6.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.75 | 19 | 7.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.00 | 20 | 8.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1.25 | 21 | 10.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1.50 | 22 | 12.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.75 | 23 | 14.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.00 | 24 | 16.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1.25 | 25 | 20.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1.50 | 26 | 24.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1.75 | 27 | 28.000 | +Normal | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.00 | 28 | 32.000 | +Infinity | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1.25 | 29 | 40.000 | NaN | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1.50 | 30 | 48.000 | NaN | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1.75 | 31 | 56.000 | NaN |

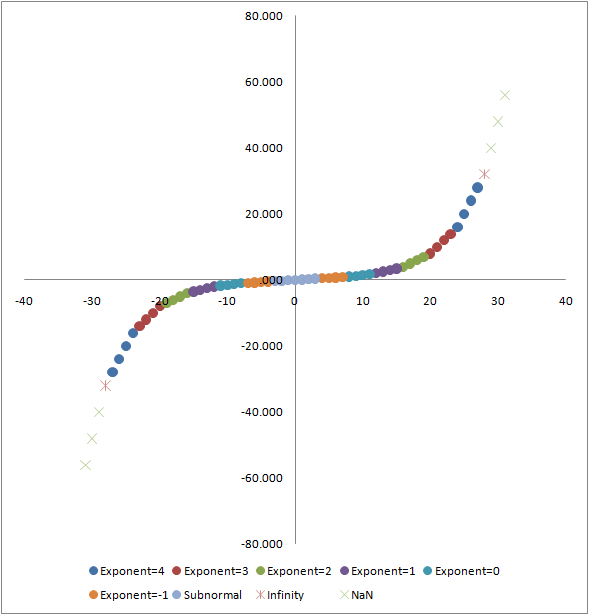

Which is a pretty nice, compact summary of how the IEEE floating point format works. However, if we graph the results, we see that the floating point values follow an interesting curve:

Again, the horizontal axis is the naive interpretation of the 6 bits as an integer (though the sign is kept as a separate bit, rather than using two’s complement). The vertical axis is the actual floating point value represented by those bits, according the the IEEE-ish minifloat format we chose.

As you can see, the distribution is not linear. In fact, and I suppose unsurprisingly, the distribution is exponential.

Actually, within each exponent band, the distribution is linear, which I have color-coded in the graph above. The exponent of each band is basically the slope of the line along which the values are evenly distributed. You can also see that the floating point values close to 0 are densely packed along the vertical axis, while the larger floating point values are spread out along the vertical axis. The spacing along the horizontal axis is fixed.

Which leads us back to our problem: presumably errors in floating point math are accumulated in the least significant bits. But the least significant bits can actually represent quite a range of values, from very small to very large. For instance, in our minifloat format used above, you can see that the least significant bit caused the smallest representation larger than 0 to be 0.125, while the least significant bit caused the next-to-largest value to change by 4.0 to become the largest value.

And that is just in our silly minifloat format. We can do the math for the full 64-bit format. The least-significant bit in the 64-bit double-precision floating point format can range in value from:

In absolute terms, that is a mind-boggling range of possible errors.

Introducing the Binary64 type

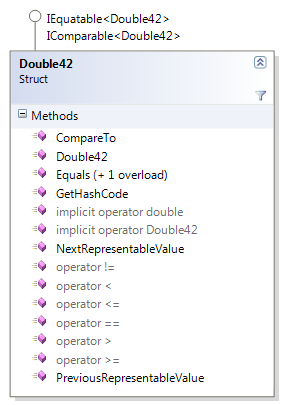

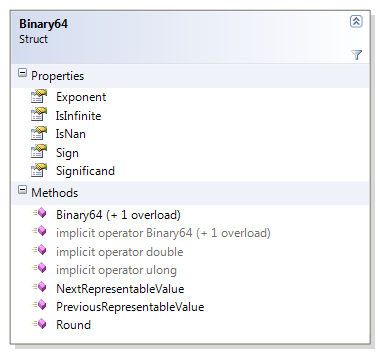

For experimentation and investigation into the structure of the binary64 format (double in C#) I’ve built the Binary64 class which you can find on my codeplex site.

The Binary64 struct uses explicit field offsets to overlap a 64-bit double with a 64-bit ulong – the managed equivalent of a union. The size of this struct is still 64-bits, so is as efficient to pass around as either a double or a uint.

A Binary64 can be constructed from either a double or a ulong, and it can be implicitly casted to and from either one. There are also methods to get the next and previous representable values. Knowing what we know now, it is clear that these just increment and decrement the ulong – except for handling a few cases, such as positive and negative 0.

The Binary64 struct also exposes the interesting pieces of a floating point number: the sign, the exponent, and the significand. I exposed these carefully through types, such as a Binary64Exponent for the exponent, and a Binary64Significand for the significand.

As a side-note, I also provide extension methods via the DoubleExtensions class to add most of this functionality to the double class.

And finally, I provide a Round method , which we will discuss next.

Investigating the error

What exactly was wrong with the 0.8 – 0.7 == 0.1 condition at the start of this article? Using the Binary64 class, it is easy to investigate.

| Literal Value | 0.8 |

| Binary64 Bits | 0x3FE999999999999A |

| Sign | Positive |

| Unbiased Exponent | 0x3FE |

| Biased Exponent | -1 |

| Significand | 0x000999999999999A |

| Implicit leading digit? | Yes |

| Significand Numerator | 7,205,759,403,792,794 |

| Significand Denominator | 4,503,599,627,370,496 |

| Significand Fraction | 1.6000000000000000888178419700125 |

So, the actual value is a little more than 0.8 due to the difficulty of encoding this exact value in base 2. Note that the previous representable value is a little less than 0.8.

| Literal Value | 0.7 |

| Binary64 Bits | 0x3FE6666666666666 |

| Sign | Positive |

| Unbiased Exponent | 0x3FE |

| Biased Exponent | -1 |

| Significand | 0x0006666666666666 |

| Implicit leading digit? | Yes |

| Significand Numerator | 6,305,039,478,318,694 |

| Significand Denominator | 4,503,599,627,370,496 |

| Significand Fraction | 1.3999999999999999111821580299875 |

So the actual value is a little less than 0.7 due to the same difficulty of representing this exact number in base 2. Note that the next representable value is a little more than 0.7.

Obviously, since we are dealing with two inexact representations, there is an error accumulating in each. The result of any math operation will likely still contain the error. Indeed, we can see:

| Literal Value | 0.8 - 0.7 |

| Binary64 Bits | 0x3fb99999999999A0 |

| Sign | Positive |

| Unbiased Exponent | 0x3FB |

| Biased Exponent | -4 |

| Significand | 0x00099999999999A0 |

| Implicit leading digit? | Yes |

| Significand Numerator | 7,205,759,403,792,800 |

| Significand Denominator | 4,503,599,627,370,496 |

| Significand Fraction | 1.6000000000000014210854715202004 |

Obviously this is not exactly right either. But more interestingly, there are 6 representable binary64 values between the result of calculating 0.8-0.7 and the literal 0.1. Looking at the binary64 representation for each we see that the error has accumulated in the least significant 6 bits:

| 0.8 - 0.7 | 0x3FB99999999999A0

11111110111001100110011001100110011001100110011001100110100000 |

| 0.1 | 0x3FB999999999999A

11111110111001100110011001100110011001100110011001100110011010 |

Proposal: Rounding by reducing precision

As we have seen, floating point math is imprecise, and rounding strategies are challenging due to the huge range in the magnitude of error introduced by a single change in the least significant bit.

I propose performing calculations in higher precision than comparisons. This is not really a novel idea. Graphics cards, for instance, have been able to perform calculations in the pipeline at higher precision than available programmatically in pixel shaders. When reducing precision for comparison, we would obviously discard the least-significant bits first.

To implement rounding, not just truncation, I use the trick of adding half before truncating. The Binary64.Round method takes as a parameter the number of insignificant digits. Based on this it can easily calculate the number of representable floating-point numbers in those insignificant digits, and it adds half of them before clearing those insignificant digits.

Remember – this kind of rounding is about rounding to the nearest nth-representable value, it isn’t about rounding in any absolute sense. Just think of it as reducing precision.

For floating point numbers, the precision of comparison is so important I think it should be part of the type signature. C++ could use int values in a template signature, but sadly C# cannot do the same with generics. If it could we could have a sweet template like Binary64Compare<42> to represent a 42-bit significand instead of the standard 52 (ignoring the implicit leading digit). Such a type would clearly indicate that the 10 least-significant bits are considered to accumulate error and will be rounded away.

Introducing the Double42 type

Since I want to encode the precision information in the type, and given the limitations of .Net generics, the next best thing we can do is declare concrete types. For my purposes, I made the assumption that 10 bits of error was a reasonable amount to tolerate. You can make your own domain-specific choice and implement your own class.

The Double42 struct just containts a double, so it should be as efficient to pass around as a double. It does not change the value of the double, but performs rounding as needed internally.

A Double42 can be constructed from a double , and it can be implicitly casted to and from a double.

This type is only intended for comparison, in support of the principal of doing calculations in higher precision than comparisons, so it does not offer any mathematical operations. It implements both IEquatable and IComparable.

As mentioned in the beginning of this article, Double42 also implements GetHashcode and Equals correctly, so that any two numbers that are “equal” also produce the same hashcode.

Finally, we get to write the code we wanted in the first place:

double a = 0.8 - 0.7;

if ((Double42)a == 0.1)

{

Console.WriteLine("Math makes sense.");

}

The supporting code for this blog entry can be found on my codeplex site: <microsoftdwayneneed.codeplex.com>

Comments

Anonymous

January 05, 2012

This is pretty cool. I'm going to use this idea in a project I'm working on right now. Thanks!Anonymous

October 13, 2013

Double42.CompareTo() does not work with negative numbers. The buts of the double values are compared directly as ulong and this works only for positive numbers. It can be fixed by adding this code before the if-statement: long a_long = (long)a.Bits; long b_long = (long)b.Bits; unchecked { // Make the longs lexicographically ordered as a twos-complement longs if (a_long < 0) a_long = (long)Binary64.BITS_SIGN - a_long; if (b_long < 0) b_long = (long)Binary64.BITS_SIGN - b_long; }Anonymous

October 13, 2013

Forgot, the comparison must then be done on the casted long values instead of the ulong values. So the full replacement for Double42.CompareTo to work with negative values, or mixed positive and negative values is this: public int CompareTo(Double42 other) { Binary64 a = new Binary64(_value); Binary64 b = new Binary64(other._value); if (a.IsNan || b.IsNan) { throw new ArithmeticException("CompareTo cannot accept Nans."); } // Round away the insignificant bits of both. a = a.Round(INSIGNIFICANT_BITS); b = b.Round(INSIGNIFICANT_BITS); // Need to take care when comparing negative and positive numbers: // en.wikipedia.org/.../IEEE_754-1985: // "The binary representation has the special property that, excluding NaNs, any two numbers can be // compared like sign and magnitude integers (although with modern computer processors this is no // longer directly applicable): if the sign bit is different, the negative number precedes the // positive number (except that negative zero and positive zero should be considered equal), otherwise, // relative order is the same as lexicographical order but inverted for two negative numbers; endianness issues apply." long a_long = (long)a.Bits; long b_long = (long)b.Bits; unchecked { // Make the longs lexicographically ordered as a twos-complement longs if (a_long < 0) a_long = (long)Binary64.BITS_SIGN - a_long; if (b_long < 0) b_long = (long)Binary64.BITS_SIGN - b_long; } if (a_long < b_long) return -1; else if (a_long > b_long) return 1; else return 0; }

![clip_image002[10] clip_image002[10]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B10%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[12] clip_image002[12]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B12%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[14] clip_image002[14]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B14%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[16] clip_image002[16]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B16%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[26] clip_image002[26]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B26%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B1%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[3] clip_image002[3]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B3%5D_thumb.gif)

![clip_image002[5] clip_image002[5]](https://msdntnarchive.z22.web.core.windows.net/media/TNBlogsFS/BlogFileStorage/blogs_msdn/dwayneneed/WindowsLiveWriter/Funwithfloatingpoint_14F06/clip_image002%5B5%5D_thumb.gif)