Transaction locking and row versioning guide

Applies to:

SQL Server

Azure SQL Database

Azure SQL Managed Instance

Azure Synapse Analytics

Analytics Platform System (PDW)

SQL database in Microsoft Fabric

In any database, mismanagement of transactions often leads to contention and performance problems in systems that have many users. As the number of users that access the data increases, it becomes important to have applications that use transactions efficiently. This guide describes locking and row versioning mechanisms the Database Engine uses to ensure the integrity of each transaction and provides information on how applications can control transactions efficiently.

Note

Optimized locking is a Database Engine feature introduced in 2023 that drastically reduces lock memory, and the number of locks required for concurrent writes. This article has been updated to describe the Database Engine behavior with and without optimized locking.

- For more information and to learn where optimized locking is available, see Optimized locking.

- To determine if optimized locking is enabled on your database, see Is optimized locking enabled?

Optimized locking has introduced significant changes to some sections of this article, including:

Transaction basics

A transaction is a sequence of operations performed as a single logical unit of work. A logical unit of work must exhibit four properties, called the atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID) properties, to qualify as a transaction.

Atomicity

A transaction must be an atomic unit of work; either all of its data modifications are performed, or none of them are performed.

Consistency

When completed, a transaction must leave all data in a consistent state. In a relational database, all rules must be applied to the transaction's modifications to maintain all data integrity. All internal data structures, such as B-tree indexes or doubly linked lists, must be correct at the end of the transaction.

Note

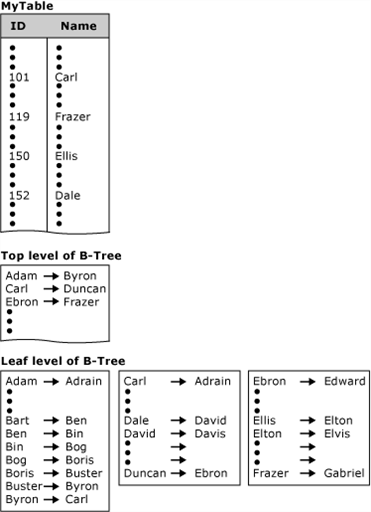

Documentation uses the term B-tree generally in reference to indexes. In rowstore indexes, the Database Engine implements a B+ tree. This does not apply to columnstore indexes or indexes on memory-optimized tables. For more information, see the SQL Server and Azure SQL index architecture and design guide.

Isolation

Modifications made by concurrent transactions must be isolated from the modifications made by any other concurrent transactions. A transaction either recognizes data in the state it was in before another concurrent transaction modified it, or it recognizes the data after the second transaction has completed, but it doesn't recognize an intermediate state. This is referred to as serializability because it results in the ability to reload the starting data and replay a series of transactions to end up with the data in the same state it was in after the original transactions were performed.

Durability

After a fully durable transaction has completed, its effects are permanently in place in the system. The modifications persist even in the event of a system failure. SQL Server 2014 (12.x) and later enable delayed durable transactions. Delayed durable transactions commit before the transaction log record is persisted to disk. For more information on delayed transaction durability, see the article Control Transaction Durability.

Applications are responsible for starting and ending transactions at points that enforce the logical consistency of the data. The application must define the sequence of data modifications that leave the data in a consistent state relative to the organization's business rules. The application performs these modifications in a single transaction so that the Database Engine can enforce the integrity of the transaction.

It is the responsibility of an enterprise database system, such as an instance of the Database Engine, to provide mechanisms ensuring the integrity of each transaction. The Database Engine provides:

Locking facilities that preserve transaction isolation.

Logging facilities to ensure transaction durability. For fully durable transactions the log record is hardened to disk before the transactions commits. Thus, even if the server hardware, operating system, or the instance of the Database Engine itself fails, the instance uses the transaction logs upon restart to automatically roll back any incomplete transactions to the point of the system failure. Delayed durable transactions commit before the transaction log record is hardened to disk. Such transactions may be lost if there is a system failure before the log record is hardened to disk. For more information on delayed transaction durability, see the article Control Transaction Durability.

Transaction management features that enforce transaction atomicity and consistency. After a transaction has started, it must be successfully completed (committed), or the Database Engine undoes all of the data modifications made by the transaction since the transaction started. This operation is referred to as rolling back a transaction because it returns the data to the state it was prior to those changes.

Control transactions

Applications control transactions mainly by specifying when a transaction starts and ends. This can be specified by using either Transact-SQL statements or database application programming interface (API) functions. The system must also be able to correctly handle errors that terminate a transaction before it completes. For more information, see Transactions, Performing Transactions in ODBC, and Transactions in SQL Server Native Client.

By default, transactions are managed at the connection level. When a transaction is started on a connection, all Transact-SQL statements executed on that connection are part of the transaction until the transaction ends. However, under a multiple active result set (MARS) session, a Transact-SQL explicit or implicit transaction becomes a batch-scoped transaction that is managed at the batch level. When the batch completes, if the batch-scoped transaction isn't committed or rolled back, it is automatically rolled back by the Database Engine. For more information, see Using Multiple Active Result Sets (MARS).

Start transactions

Using API functions and Transact-SQL statements, you can start transactions as explicit, autocommit, or implicit transactions.

Explicit transactions

An explicit transaction is one in which you explicitly define both the start and end of the transaction through an API function or by issuing the Transact-SQL BEGIN TRANSACTION, COMMIT TRANSACTION, COMMIT WORK, ROLLBACK TRANSACTION, or ROLLBACK WORK Transact-SQL statements. When the transaction ends, the connection returns to the transaction mode it was in before the explicit transaction was started, which might be the implicit or autocommit mode.

You can use all Transact-SQL statements in an explicit transaction, except for the following statements:

CREATE DATABASEALTER DATABASEDROP DATABASECREATE FULLTEXT CATALOGALTER FULLTEXT CATALOGDROP FULLTEXT CATALOGDROP FULLTEXT INDEXALTER FULLTEXT INDEXCREATE FULLTEXT INDEXBACKUPRESTORERECONFIGURE- Full-text system stored procedures

sp_dboptionto set database options or any system procedure that modifies themasterdatabase inside explicit or implicit transactions.

Note

UPDATE STATISTICS can be used inside an explicit transaction. However, UPDATE STATISTICS commits independently of the enclosing transaction and cannot be rolled back.

Autocommit Transactions

Autocommit mode is the default transaction management mode of the Database Engine. Every Transact-SQL statement is committed or rolled back when it completes. If a statement completes successfully, it is committed; if it encounters any error, it is rolled back. A connection to an instance of the Database Engine operates in autocommit mode whenever this default mode hasn't been overridden by either explicit or implicit transactions. Autocommit mode is also the default mode for SqlClient, ADO, OLE DB, and ODBC.

Implicit Transactions

When a connection is operating in implicit transaction mode, the instance of the Database Engine automatically starts a new transaction after the current transaction is committed or rolled back. You do nothing to delineate the start of a transaction; you only commit or roll back each transaction. Implicit transaction mode generates a continuous chain of transactions. Set implicit transaction mode on through either an API function or the Transact-SQL SET IMPLICIT_TRANSACTIONS ON statement. This mode is also known as Autocommit OFF, see setAutoCommit Method (SQLServerConnection).

After implicit transaction mode has been set on for a connection, the instance of the Database Engine automatically starts a transaction when it first executes any of these statements:

ALTER TABLECREATEDELETEDENYDROPFETCHGRANTINSERTOPENREVOKESELECTTRUNCATEUPDATE

Batch-scoped Transactions

Applicable only to multiple active result sets (MARS), a Transact-SQL explicit or implicit transaction that starts under a MARS session becomes a batch-scoped transaction. A batch-scoped transaction that isn't committed or rolled back when a batch completes is automatically rolled back by the Database Engine.

Distributed transactions

Distributed transactions span two or more servers known as resource managers. The management of the transaction must be coordinated between the resource managers by a server component called a transaction manager. Each instance of the Database Engine can operate as a resource manager in distributed transactions coordinated by transaction managers, such as Microsoft Distributed Transaction Coordinator (MS DTC), or other transaction managers that support the Open Group XA specification for distributed transaction processing. For more information, see the MS DTC documentation.

A transaction within a single instance of the Database Engine that spans two or more databases is a distributed transaction. The instance manages the distributed transaction internally; to the user, it operates as a local transaction.

In the application, a distributed transaction is managed much the same as a local transaction. At the end of the transaction, the application requests the transaction to be either committed or rolled back. A distributed commit must be managed differently by the transaction manager to minimize the risk that a network failure may result in some resource managers successfully committing while others roll back the transaction. This is achieved by managing the commit process in two phases (the prepare phase and the commit phase), which is known as a two-phase commit.

Prepare phase

When the transaction manager receives a commit request, it sends a prepare command to all of the resource managers involved in the transaction. Each resource manager then does everything required to make the transaction durable, and all transaction log buffers for the transaction are flushed to disk. As each resource manager completes the prepare phase, it returns success or failure of the prepare to the transaction manager. SQL Server 2014 (12.x) introduced delayed transaction durability. Delayed durable transactions commit before the transaction log buffers on each resource manager are flushed to disk. For more information on delayed transaction durability, see the article Control Transaction Durability.

Commit phase

If the transaction manager receives successful prepares from all of the resource managers, it sends commit commands to each resource manager. The resource managers can then complete the commit. If all of the resource managers report a successful commit, the transaction manager then sends a success notification to the application. If any resource manager reported a failure to prepare, the transaction manager sends a rollback command to each resource manager and indicates the failure of the commit to the application.

Database Engine applications can manage distributed transactions either through Transact-SQL or through the database API. For more information, see BEGIN DISTRIBUTED TRANSACTION (Transact-SQL).

End transactions

You can end transactions with either a COMMIT or ROLLBACK statement, or through a corresponding API function.

Commit

If a transaction is successful, commit it. A

COMMITstatement guarantees all of the transaction's modifications are made a permanent part of the database. A commit also frees resources, such as locks, used by the transaction.Roll back

If an error occurs in a transaction, or if the user decides to cancel the transaction, roll back the transaction. A

ROLLBACKstatement backs out all modifications made in the transaction by returning the data to the state it was in at the start of the transaction. Roll back also frees resources held by the transaction.

Note

On multiple active result sets (MARS) sessions, an explicit transaction started through an API function cannot be committed while there are pending execution requests. Any attempt to commit this type of transaction while there are executing requests will result in an error.

Errors during transaction processing

If an error prevents the successful completion of a transaction, the Database Engine automatically rolls back the transaction and frees all resources held by the transaction. If the client network connection to an instance of the Database Engine is broken, any outstanding transactions for the connection are rolled back when the network notifies the instance of the connection break. If the client application fails or if the client computer goes down or is restarted, this also breaks the connection, and the instance of the Database Engine rolls back any outstanding transactions when the network notifies it of the connection break. If the client disconnects from the Database Engine, any outstanding transactions are rolled back.

If a run-time statement error (such as a constraint violation) occurs in a batch, the default behavior in the Database Engine is to roll back only the statement that generated the error. You can change this behavior using the SET XACT_ABORT ON statement. After SET XACT_ABORT ON is executed, any run-time statement error causes an automatic rollback of the current transaction. Compile errors, such as syntax errors, are not affected by SET XACT_ABORT. For more information, see SET XACT_ABORT (Transact-SQL).

When errors occur, the appropriate action (COMMIT or ROLLBACK) should be included in application code. One effective tool for handling errors, including those in transactions, is the Transact-SQL TRY...CATCH construct. For more information with examples that include transactions, see TRY...CATCH (Transact-SQL). Beginning with SQL Server 2012 (11.x), you can use the THROW statement to raise an exception and transfers execution to a CATCH block of a TRY...CATCH construct. For more information, see THROW (Transact-SQL).

Compile and run-time errors in autocommit mode

In autocommit mode, it sometimes appears as if an instance of the Database Engine has rolled back an entire batch instead of just one SQL statement. This happens if the error encountered is a compile error, not a run-time error. A compile error prevents the Database Engine from building an execution plan, hence nothing in the batch can be executed. Although it appears that all of the statements before the one generating the error were rolled back, the error prevented anything in the batch from being executed. In the following example, none of the INSERT statements in the third batch are executed because of a compile error. It appears that the first two INSERT statements are rolled back when they are never executed.

CREATE TABLE TestBatch (ColA INT PRIMARY KEY, ColB CHAR(3));

GO

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (1, 'aaa');

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (2, 'bbb');

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUSE (3, 'ccc'); -- Syntax error.

GO

SELECT * FROM TestBatch; -- Returns no rows.

GO

In the following example, the third INSERT statement generates a run-time duplicate primary key error. The first two INSERT statements are successful and committed, so they remain after the run-time error.

CREATE TABLE TestBatch (ColA INT PRIMARY KEY, ColB CHAR(3));

GO

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (1, 'aaa');

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (2, 'bbb');

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (1, 'ccc'); -- Duplicate key error.

GO

SELECT * FROM TestBatch; -- Returns rows 1 and 2.

GO

The Database Engine uses deferred name resolution, where object names are resolved at execution time, not at compilation time. In the following example, the first two INSERT statements are executed and committed, and those two rows remain in the TestBatch table after the third INSERT statement generates a run-time error by referring to a table that doesn't exist.

CREATE TABLE TestBatch (ColA INT PRIMARY KEY, ColB CHAR(3));

GO

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (1, 'aaa');

INSERT INTO TestBatch VALUES (2, 'bbb');

INSERT INTO TestBch VALUES (3, 'ccc'); -- Table name error.

GO

SELECT * FROM TestBatch; -- Returns rows 1 and 2.

GO

Locking and row versioning basics

The Database Engine uses the following mechanisms to ensure the integrity of transactions and maintain the consistency of databases when multiple users are accessing data at the same time:

Locking

Each transaction requests locks of different types on the resources, such as rows, pages, or tables, on which the transaction is dependent. The locks block other transactions from modifying the resources in a way that would cause problems for the transaction requesting the lock. Each transaction frees its locks when it no longer has a dependency on the locked resources.

Row versioning

When a row versioning based isolation level is used, the Database Engine maintains versions of each row that is modified. Applications can specify that a transaction use the row versions to view data as it existed at the start of the transaction or statement, instead of protecting all reads with locks. By using row versioning, the chance that a read operation will block other transactions is greatly reduced.

Locking and row versioning prevent users from reading uncommitted data and prevent multiple users from attempting to change the same data at the same time. Without locking or row versioning, queries executed against that data could produce unexpected results by returning data that hasn't yet been committed in the database.

Applications can choose transaction isolation levels, which define the level of protection for the transaction from modifications made by other transactions. Table-level hints can be specified for individual Transact-SQL statements to further tailor the behavior to fit the requirements of the application.

Manage concurrent data access

Users who access a resource at the same time are said to be accessing the resource concurrently. Concurrent data access requires mechanisms to prevent adverse effects when multiple users try to modify resources that other users are actively using.

Concurrency effects

Users modifying data can affect other users who are reading or modifying the same data at the same time. These users are said to be accessing the data concurrently. If a database has no concurrency control, users could see the following side effects:

Lost updates

Lost updates occur when two or more transactions select the same row and then update the row based on the value originally selected. Each transaction is unaware of the other transactions. The last update overwrites updates made by the other transactions, which results in lost data.

For example, two editors make an electronic copy of the same document. Each editor changes the copy independently and then saves the changed copy thereby overwriting the original document. The editor who saves the changed copy last overwrites the changes made by the other editor. This problem could be avoided if one editor could not access the file until the other editor had finished and committed the transaction.

Uncommitted dependency (dirty read)

Uncommitted dependency occurs when a second transaction reads a row that is being updated by another transaction. The second transaction is reading data that hasn't been committed yet and may be changed by the transaction updating the row.

For example, an editor is making changes to an electronic document. During the changes, a second editor takes a copy of the document that includes all the changes made so far, and distributes the document to the intended audience. The first editor then decides the changes made so far are wrong and removes the edits and saves the document. The distributed document contains edits that no longer exist and should be treated as if they never existed. This problem could be avoided if no one could read the changed document until the first editor does the final save of modifications and commits the transaction.

Inconsistent analysis (nonrepeatable read)

Inconsistent analysis occurs when a second transaction accesses the same row several times and reads different data each time. Inconsistent analysis is similar to uncommitted dependency in that another transaction is changing the data that a second transaction is reading. However, in inconsistent analysis, the data read by the second transaction was committed by the transaction that made the change. Also, inconsistent analysis involves multiple reads (two or more) of the same row, and each time the information is changed by another transaction; thus, the term nonrepeatable read.

For example, an editor reads the same document twice, but between each reading the writer rewrites the document. When the editor reads the document for the second time, it has changed. The original read was not repeatable. This problem could be avoided if the writer could not change the document until the editor has finished reading it for the last time.

Phantom reads

A phantom read is a situation that occurs when two identical queries are executed and the set of rows returned by the second query is different. The example below shows how this may occur. Assume the two transactions below are executing at the same time. The two

SELECTstatements in the first transaction may return different results because theINSERTstatement in the second transaction changes the data used by both.--Transaction 1 BEGIN TRAN; SELECT ID FROM dbo.employee WHERE ID > 5 AND ID < 10; --The INSERT statement from the second transaction occurs here. SELECT ID FROM dbo.employee WHERE ID > 5 and ID < 10; COMMIT;--Transaction 2 BEGIN TRAN; INSERT INTO dbo.employee (Id, Name) VALUES(6 ,'New'); COMMIT;Missing and double reads caused by row updates

Missing an updated row or seeing an updated row multiple times

Transactions that are running at the

READ UNCOMMITTEDlevel (or statements using theNOLOCKtable hint) do not issue shared locks to prevent other transactions from modifying data read by the current transaction. Transactions that are running at theREAD COMMITTEDlevel do issue shared locks, but the row or page locks are released after the row is read. In either case, when you are scanning an index, if another user changes the index key column of the row during your read, the row might appear again if the key change moved the row to a position ahead of your scan. Similarly, the row might not be read at all if the key change moved the row to a position in the index that you had already read. To avoid this, use theSERIALIZABLEorHOLDLOCKhint, or row versioning. For more information, see Table Hints (Transact-SQL).Missing one or more rows that were not the target of update

When you are using

READ UNCOMMITTED, if your query reads rows using an allocation order scan (using IAM pages), you might miss rows if another transaction is causing a page split. This does not occur when you are using theREAD COMMITTEDisolation level.

Types of concurrency

When multiple transactions attempt to modify data in a database at the same time, a system of controls must be implemented so that modifications made by one transaction do not adversely affect those of another transaction. This is called concurrency control.

Concurrency control theory has two classifications for the methods of instituting concurrency control:

Pessimistic concurrency control

A system of locks prevents transactions from modifying data in a way that affects other transactions. After a transactions performs an action that causes a lock to be applied, other transactions cannot perform actions that would conflict with the lock until the owner releases it. This is called pessimistic control because it is mainly used in environments where there is high contention for data, where the cost of protecting data with locks is less than the cost of rolling back transactions if concurrency conflicts occur.

Optimistic concurrency control

In optimistic concurrency control, transactions do not lock data when they read it. However, when a transaction updates data, the system checks to see if another transaction changed the data after it was read. If another transaction updated the data, an error is raised. Typically, the transaction receiving the error rolls back and starts over. This is called optimistic because it is mainly used in environments where there is low contention for data, and where the cost of occasionally rolling back a transaction is lower than the cost of locking data when read.

The Database Engine supports both concurrency control methods. Users specify the type of concurrency control by selecting transaction isolation levels for connections or concurrency options on cursors. These attributes can be defined using Transact-SQL statements, or through the properties and attributes of database application programming interfaces (APIs) such as ADO, ADO.NET, OLE DB, and ODBC.

Isolation levels in the Database Engine

Transactions specify an isolation level that defines the degree to which one transaction must be isolated from the resource or data modifications made by other transactions. Isolation levels are described in terms of which concurrency side-effects, such as dirty reads or phantom reads, are allowed.

Transaction isolation levels control:

- Whether locks are acquired when data is read, and what type of locks are requested.

- How long the read locks are held.

- Whether a read operation referencing rows modified by another transaction:

- Blocks until the exclusive lock on the row is freed.

- Retrieves the committed version of the row that existed at the time the statement or transaction started.

- Reads the uncommitted data modification.

Important

Choosing a transaction isolation level does not affect the locks acquired to protect data modifications. A transaction always holds an exclusive lock to perform data modification, and holds that lock until the transaction completes, regardless of the isolation level set for that transaction. For read operations, transaction isolation levels primarily define the level of protection from the effects of modifications made by other transactions.

A lower isolation level increases the ability of many transactions to access data at the same time, but also increases the number of concurrency effects (such as dirty reads or lost updates) transactions might encounter. Conversely, a higher isolation level reduces the types of concurrency effects that transactions may encounter, but requires more system resources and increases the chances that one transaction will block another. Choosing the appropriate isolation level depends on balancing the data integrity requirements of the application against the overhead of each isolation level. The highest isolation level, SERIALIZABLE, guarantees that a transaction will retrieve exactly the same data every time it repeats a read operation, but it does this by performing a level of locking that is likely to impact other transactions in multi-user systems. The lowest isolation level, READ UNCOMMITTED, may retrieve data that has been modified but not committed by other transactions. All of the concurrency side effects can happen in READ UNCOMMITTED, but there is no read locking or versioning, so overhead is minimized.

Database Engine isolation levels

The ISO standard defines the following isolation levels, all of which are supported by the Database Engine:

| Isolation Level | Definition |

|---|---|

READ UNCOMMITTED |

The lowest isolation level where transactions are isolated only enough to ensure that physically inconsistent data isn't read. In this level, dirty reads are allowed, so one transaction may see not-yet-committed changes made by other transactions. |

READ COMMITTED |

Allows a transaction to read data previously read (not modified) by another transaction without waiting for the first transaction to complete. The Database Engine keeps write locks (acquired on selected data) until the end of the transaction, but read locks are released as soon as the read operation is performed. This is the Database Engine default level. |

REPEATABLE READ |

The Database Engine keeps read and write locks that are acquired on selected data until the end of the transaction. However, because range-locks are not managed, phantom reads can occur. |

SERIALIZABLE |

The highest level where transactions are completely isolated from one another. The Database Engine keeps read and write locks acquired on selected data until the end of the transaction. Range-locks are acquired when a SELECT operation uses a range WHERE clause to avoid phantom reads. Note: DDL operations and transactions on replicated tables may fail when the SERIALIZABLE isolation level is requested. This is because replication queries use hints that may be incompatible with the SERIALIZABLE isolation level. |

The Database Engine also supports two additional transaction isolation levels that use row versioning. One is an implementation of READ COMMITTED isolation level, and one is the SNAPSHOT transaction isolation level.

| Row Versioning Isolation Level | Definition |

|---|---|

Read Committed Snapshot (RCSI) |

When the READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT database option is set ON, which is the default setting in Azure SQL Database, the READ COMMITTED isolation level uses row versioning to provide statement-level read consistency. Read operations require only the schema stability (Sch-S) table level locks and no page or row locks. That is, the Database Engine uses row versioning to present each statement with a transactionally consistent snapshot of the data as it existed at the start of the statement. Locks are not used to protect the data from updates by other transactions. A user-defined function can return data that was committed after the time the statement containing the UDF began.When the READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT database option is set OFF, which is the default setting in SQL Server and Azure SQL Managed Instance, READ COMMITTED isolation uses shared locks to prevent other transactions from modifying rows while the current transaction is running a read operation. The shared locks also block the statement from reading rows modified by other transactions until the other transaction is completed. Both implementations meet the ISO definition of READ COMMITTED isolation. |

SNAPSHOT |

The snapshot isolation level uses row versioning to provide transaction-level read consistency. Read operations acquire no page or row locks; only the schema stability (Sch-S) table locks are acquired. When reading rows modified by another transaction, read operations retrieve the version of the row that existed when the transaction started. You can only use SNAPSHOT isolation when the ALLOW_SNAPSHOT_ISOLATION database option is set to ON. By default, this option is set to OFF for user databases in SQL Server and Azure SQL Managed Instance, and set to ON for databases in Azure SQL Database.Note: The Database Engine doesn't support versioning of metadata. For this reason, there are restrictions on what DDL operations can be performed in an explicit transaction that is running under snapshot isolation. The following DDL statements are not permitted under snapshot isolation after a BEGIN TRANSACTION statement: ALTER TABLE, CREATE INDEX, CREATE XML INDEX, ALTER INDEX, DROP INDEX, DBCC REINDEX, ALTER PARTITION FUNCTION, ALTER PARTITION SCHEME, or any common language runtime (CLR) DDL statement. These statements are permitted when you are using snapshot isolation within implicit transactions. An implicit transaction, by definition, is a single statement that makes it possible to enforce the semantics of snapshot isolation, even with DDL statements. Violations of this principle can cause error 3961: Snapshot isolation transaction failed in database '%.*ls' because the object accessed by the statement has been modified by a DDL statement in another concurrent transaction since the start of this transaction. It is not allowed because the metadata is not versioned. A concurrent update to metadata could lead to inconsistency if mixed with snapshot isolation. |

The following table shows the concurrency side effects enabled by the different isolation levels.

| Isolation level | Dirty read | Nonrepeatable read | Phantom |

|---|---|---|---|

READ UNCOMMITTED |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

READ COMMITTED |

No | Yes | Yes |

REPEATABLE READ |

No | No | Yes |

SNAPSHOT |

No | No | No |

SERIALIZABLE |

No | No | No |

For more information about the specific types of locking or row versioning controlled by each transaction isolation level, see SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL (Transact-SQL).

Transaction isolation levels can be set using Transact-SQL or through a database API.

Transact-SQL

Transact-SQL scripts use the SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL statement.

ADO

ADO applications set the IsolationLevel property of the Connection object to adXactReadUncommitted, adXactReadCommitted, adXactRepeatableRead, or adXactReadSerializable.

ADO.NET

ADO.NET applications using the System.Data.SqlClient managed namespace can call the SqlConnection.BeginTransaction method and set the IsolationLevel option to Unspecified, Chaos, ReadUncommitted, ReadCommitted, RepeatableRead, Serializable, or Snapshot.

OLE DB

When starting a transaction, applications using OLE DB call ITransactionLocal::StartTransaction with isoLevel set to ISOLATIONLEVEL_READUNCOMMITTED, ISOLATIONLEVEL_READCOMMITTED, ISOLATIONLEVEL_REPEATABLEREAD, ISOLATIONLEVEL_SNAPSHOT, or ISOLATIONLEVEL_SERIALIZABLE.

When specifying the transaction isolation level in autocommit mode, OLE DB applications can set the DBPROPSET_SESSION property DBPROP_SESS_AUTOCOMMITISOLEVELS to DBPROPVAL_TI_CHAOS, DBPROPVAL_TI_READUNCOMMITTED, DBPROPVAL_TI_BROWSE, DBPROPVAL_TI_CURSORSTABILITY, DBPROPVAL_TI_READCOMMITTED, DBPROPVAL_TI_REPEATABLEREAD, DBPROPVAL_TI_SERIALIZABLE, DBPROPVAL_TI_ISOLATED, or DBPROPVAL_TI_SNAPSHOT.

ODBC

ODBC applications call SQLSetConnectAttr with Attribute set to SQL_ATTR_TXN_ISOLATION and ValuePtr set to SQL_TXN_READ_UNCOMMITTED, SQL_TXN_READ_COMMITTED, SQL_TXN_REPEATABLE_READ, or SQL_TXN_SERIALIZABLE.

For snapshot transactions, applications call SQLSetConnectAttr with Attribute set to SQL_COPT_SS_TXN_ISOLATION and ValuePtr set to SQL_TXN_SS_SNAPSHOT. A snapshot transaction can be retrieved using either SQL_COPT_SS_TXN_ISOLATION or SQL_ATTR_TXN_ISOLATION.

Locking in the Database Engine

Locking is a mechanism used by the Database Engine to synchronize access by multiple users to the same piece of data at the same time.

Before a transaction acquires a dependency on the current state of a piece of data, such as by reading or modifying the data, it must protect itself from the effects of another transaction modifying the same data. The transaction does this by requesting a lock on the piece of data. Locks have different modes, such as shared (S) or exclusive (X). The lock mode defines the level of dependency the transaction has on the data. No transaction can be granted a lock that would conflict with the mode of a lock already granted on that data to another transaction. If a transaction requests a lock mode that conflicts with a lock that has already been granted on the same data, the Database Engine will pause the requesting transaction until the first lock is released.

When a transaction modifies a piece of data, it holds certain locks protecting the modification until the end of the transaction. How long a transaction holds the locks acquired to protect read operations depends on the transaction isolation level setting and whether or not optimized locking is enabled.

When optimized locking isn't enabled, row and page locks necessary for writes are held until the end of the transaction.

When optimized locking is enabled, only a Transaction ID (TID) lock is held until the end of the transaction. Under the default

READ COMMITTEDisolation level, transactions will not hold row and page locks necessary for writes until the end of the transaction. This reduces lock memory required and reduces the need for lock escalation. Further, when optimized locking is enabled, the lock after qualification (LAQ) optimization evaluates predicates of a query on the latest committed version of the row without acquiring a lock, improving concurrency.

All locks held by a transaction are released when the transaction completes (either commits or rolls back).

Applications do not typically request locks directly. Locks are managed internally by a part of the Database Engine called the lock manager. When an instance of the Database Engine processes a Transact-SQL statement, the Database Engine query processor determines which resources are to be accessed. The query processor determines what types of locks are required to protect each resource based on the type of access and the transaction isolation level setting. The query processor then requests the appropriate locks from the lock manager. The lock manager grants the locks if there are no conflicting locks held by other transactions.

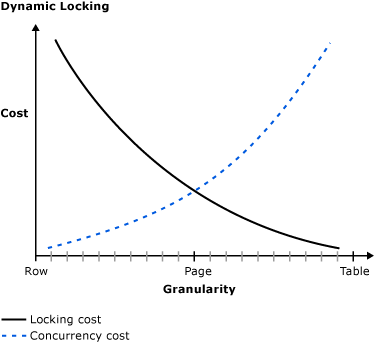

Lock granularity and hierarchies

The Database Engine has multigranular locking that allows different types of resources to be locked by a transaction. To minimize the cost of locking, the Database Engine locks resources automatically at a level appropriate to the task. Locking at a smaller granularity, such as rows, increases concurrency but has a higher overhead because more locks must be held if many rows are locked. Locking at a larger granularity, such as tables, are expensive in terms of concurrency because locking an entire table restricts access to any part of the table by other transactions. However, it has a lower overhead because fewer locks are being maintained.

The Database Engine often has to acquire locks at multiple levels of granularity to fully protect a resource. This group of locks at multiple levels of granularity is called a lock hierarchy. For example, to fully protect a read of an index, an instance of the Database Engine may have to acquire shared locks on rows and intent shared locks on the pages and table.

The following table shows the resources that the Database Engine can lock.

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

RID |

A row identifier used to lock a single row within a heap. |

KEY |

A row lock to lock a single row in a B-tree index. |

PAGE |

An 8 kilobyte (KB) page in a database, such as data or index pages. |

EXTENT |

A contiguous group of eight pages, such as data or index pages. |

HoBT 1 |

A heap or B-tree. A lock protecting a B-tree (index) or the heap data pages in a table that doesn't have a clustered index. |

TABLE 1 |

The entire table, including all data and indexes. |

FILE |

A database file. |

APPLICATION |

An application-specified resource. |

METADATA |

Metadata locks. |

ALLOCATION_UNIT |

An allocation unit. |

DATABASE |

The entire database. |

XACT 2 |

Transaction ID (TID) lock used in Optimized locking. For more information, see Transaction ID (TID) locking. |

1 HoBT and TABLE locks can be affected by the LOCK_ESCALATION option of ALTER TABLE.

2 Additional locking resources are available for XACT lock resources, see Diagnostic additions for optimized locking.

Lock modes

The Database Engine locks resources using different lock modes that determine how the resources can be accessed by concurrent transactions.

The following table shows the resource lock modes that the Database Engine uses.

| Lock mode | Description |

|---|---|

Shared (S) |

Used for read operations that do not change or update data, such as a SELECT statement. |

Update (U) |

Used on resources that can be updated. Prevents a common form of deadlock that occurs when multiple sessions are reading, locking, and potentially updating resources later. |

Exclusive (X) |

Used for data-modification operations, such as INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE. Ensures that multiple updates cannot be made to the same resource at the same time. |

| Intent | Used to establish a lock hierarchy. The types of intent locks are: intent shared (IS), intent exclusive (IX), and shared with intent exclusive (SIX). |

| Schema | Used when an operation dependent on the schema of a table is executing. The types of schema locks are: schema modification (Sch-M) and schema stability (Sch-S). |

Bulk Update (BU) |

Used when bulk copying data into a table with the TABLOCK hint. |

| Key-range | Protects the range of rows read by a query when using the SERIALIZABLE transaction isolation level. Ensures that other transactions cannot insert rows that would qualify for the queries of the SERIALIZABLE transaction if the queries were run again. |

Shared locks

Shared (S) locks allow concurrent transactions to read a resource under pessimistic concurrency control. No other transactions can modify the data while shared (S) locks exist on the resource. Shared (S) locks on a resource are released as soon as the read operation completes, unless the transaction isolation level is set to REPEATABLE READ or higher, or a locking hint is used to retain the shared (S) locks for the duration of the transaction.

Update locks

The Database Engine places update (U) locks as it prepares to execute an update. U locks are compatible with S locks, but only one transaction can hold a U lock at a time on a given resource. This is key - many concurrent transactions can hold S locks, but only one transaction can hold a U lock on a resource. Update (U) locks are eventually upgraded to exclusive (X) locks to update a row.

Update (U) locks can also be taken by statements other than UPDATE, when the UPDLOCK table hint is specified in the statement.

Some applications use the "select a row, then update the row" pattern, where the read and write are explicitly separated within the transaction. In this case, if the isolation level is

REPEATABLE READorSERIALIZABLE, concurrent updates might cause a deadlock, as follows:A transaction reads data, acquiring a shared (

S) lock on the resource, and then modifies the data, which requires lock conversion to an exclusive (X) lock. If two transactions acquire shared (S) locks on a resource and then attempt to update data concurrently, one transaction attempts the lock conversion to an exclusive (X) lock. The shared-to-exclusive lock conversion must wait because the exclusive (X) lock for one transaction isn't compatible with the shared (S) lock of the other transaction; a lock wait occurs. The second transaction attempts to acquire an exclusive (X) lock for its update. Because both transactions are converting to exclusive (X) locks, and they are each waiting for the other transaction to release its shared (S) lock, a deadlock occurs.In the default

READ COMMITTEDisolation level,Slocks are short duration, released as soon as they are used. While the deadlock described above is still possible, it is much less likely with short duration locks.To avoid this type of deadlock, applications can follow a "select a row with

UPDLOCKhint, then update the row" pattern.If the

UPDLOCKhint is used in a write whenSNAPSHOTisolation is in use, the transaction must have access to the latest version of the row. If the latest version is no longer visible, it is possible to receiveMsg 3960, Level 16, State 2 Snapshot isolation transaction aborted due to update conflict. For an example, see Work with snapshot isolation.

Exclusive locks

Exclusive (X) locks prevent access to a resource by concurrent transactions. With an exclusive (X) lock, no other transactions can modify the data protected by the lock; read operations can take place only with the use of the NOLOCK hint or the READ UNCOMMITTED isolation level.

Data modification statements, such as INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE combine both read and modification operations. The statement first performs read operations to acquire data before performing the required modification operations. Data modification statements, therefore, typically request both shared locks and exclusive locks. For example, an UPDATE statement might modify rows in one table based on a join with another table. In this case, the UPDATE statement requests shared locks on the rows read in the join table in addition to requesting exclusive locks on the updated rows.

Intent locks

The Database Engine uses intent locks to protect placing a shared (S) lock or exclusive (X) lock on a resource lower in the lock hierarchy. Intent locks are named "intent locks" because they're acquired before a lock at the lower level and, therefore, signal intent to place locks at a lower level.

Intent locks serve two purposes:

- To prevent other transactions from modifying the higher-level resource in a way that would invalidate the lock at the lower level.

- To improve the efficiency of the Database Engine in detecting lock conflicts at the higher level of granularity.

For example, a shared intent lock is requested at the table level before shared (S) locks are requested on pages or rows within that table. Setting an intent lock at the table level prevents another transaction from subsequently acquiring an exclusive (X) lock on the table containing that page. Intent locks improve performance because the Database Engine examines intent locks only at the table level to determine if a transaction can safely acquire a lock on that table. This removes the requirement to examine every row or page lock on the table to determine if a transaction can lock the entire table.

Intent locks include intent shared (IS), intent exclusive (IX), and shared with intent exclusive (SIX).

| Lock mode | Description |

|---|---|

Intent shared (IS) |

Protects requested or acquired shared locks on some (but not all) resources lower in the hierarchy. |

Intent exclusive (IX) |

Protects requested or acquired exclusive locks on some (but not all) resources lower in the hierarchy. IX is a superset of IS, and it also protects requesting shared locks on lower level resources. |

Shared with intent exclusive (SIX) |

Protects requested or acquired shared locks on all resources lower in the hierarchy and intent exclusive locks on some (but not all) of the lower level resources. Concurrent IS locks at the top-level resource are allowed. For example, acquiring a SIX lock on a table also acquires intent exclusive locks on the pages being modified and exclusive locks on the modified rows. There can be only one SIX lock per resource at one time, preventing updates to the resource made by other transactions, although other transactions can read resources lower in the hierarchy by obtaining IS locks at the table level. |

Intent update (IU) |

Protects requested or acquired update locks on all resources lower in the hierarchy. IU locks are used only on page resources. IU locks are converted to IX locks if an update operation takes place. |

Shared intent update (SIU) |

A combination of S and IU locks, as a result of acquiring these locks separately and simultaneously holding both locks. For example, a transaction executes a query with the PAGLOCK hint and then executes an update operation. The query with the PAGLOCK hint acquires the S lock, and the update operation acquires the IU lock. |

Update intent exclusive (UIX) |

A combination of U and IX locks, as a result of acquiring these locks separately and simultaneously holding both locks. |

Schema locks

The Database Engine uses schema modification (Sch-M) locks during a table data definition language (DDL) operation, such as adding a column or dropping a table. During the time that it is held, the Sch-M lock prevents concurrent access to the table. This means the Sch-M lock blocks all outside operations until the lock is released.

Some data manipulation language (DML) operations, such as table truncation, use Sch-M locks to prevent access to affected tables by concurrent operations.

The Database Engine uses schema stability (Sch-S) locks when compiling and executing queries. Sch-S locks do not block any transactional locks, including exclusive (X) locks. Therefore, other transactions, including those with X locks on a table, continue to run while a query is being compiled. However, concurrent DDL operations, and concurrent DML operations that acquire Sch-M locks, are blocked by the Sch-S locks.

Bulk update locks

Bulk update (BU) locks allow multiple threads to bulk load data concurrently into the same table while preventing other processes that are not bulk loading data from accessing the table. The Database Engine uses bulk update (BU) locks when both of the following conditions are true.

- You use the Transact-SQL

BULK INSERTstatement, or theOPENROWSET(BULK)function, or you use one of the Bulk Insert API commands such as .NETSqlBulkCopy, OLEDB Fast Load APIs, or the ODBC Bulk Copy APIs to bulk copy data into a table. - The

TABLOCKhint is specified or thetable lock on bulk loadtable option is set using sp_tableoption.

Tip

Unlike the BULK INSERT statement, which holds a less restrictive Bulk Update (BU) lock, INSERT INTO...SELECT with the TABLOCK hint holds an intent exclusive (IX) lock on the table. This means that you cannot insert rows using parallel insert operations.

Key-range locks

Key-range locks protect a range of rows implicitly included in a record set being read by a Transact-SQL statement while using the SERIALIZABLE transaction isolation level. Key-range locking prevents phantom reads. By protecting the ranges of keys between rows, it also prevents phantom insertions or deletions into a record set accessed by a transaction.

Lock compatibility

Lock compatibility controls whether multiple transactions can acquire locks on the same resource at the same time. If a resource is already locked by another transaction, a new lock request can be granted only if the mode of the requested lock is compatible with the mode of the existing lock. If the mode of the requested lock isn't compatible with the existing lock, the transaction requesting the new lock waits for the existing lock to be released or for the lock timeout interval to expire. For example, no lock modes are compatible with exclusive locks. While an exclusive (X) lock is held, no other transaction can acquire a lock of any kind (shared, update, or exclusive) on that resource until the exclusive (X) lock is released. Conversely, if a shared (S) lock has been applied to a resource, other transactions can also acquire a shared lock or an update (U) lock on that resource even if the first transaction hasn't completed. However, other transactions cannot acquire an exclusive lock until the shared lock has been released.

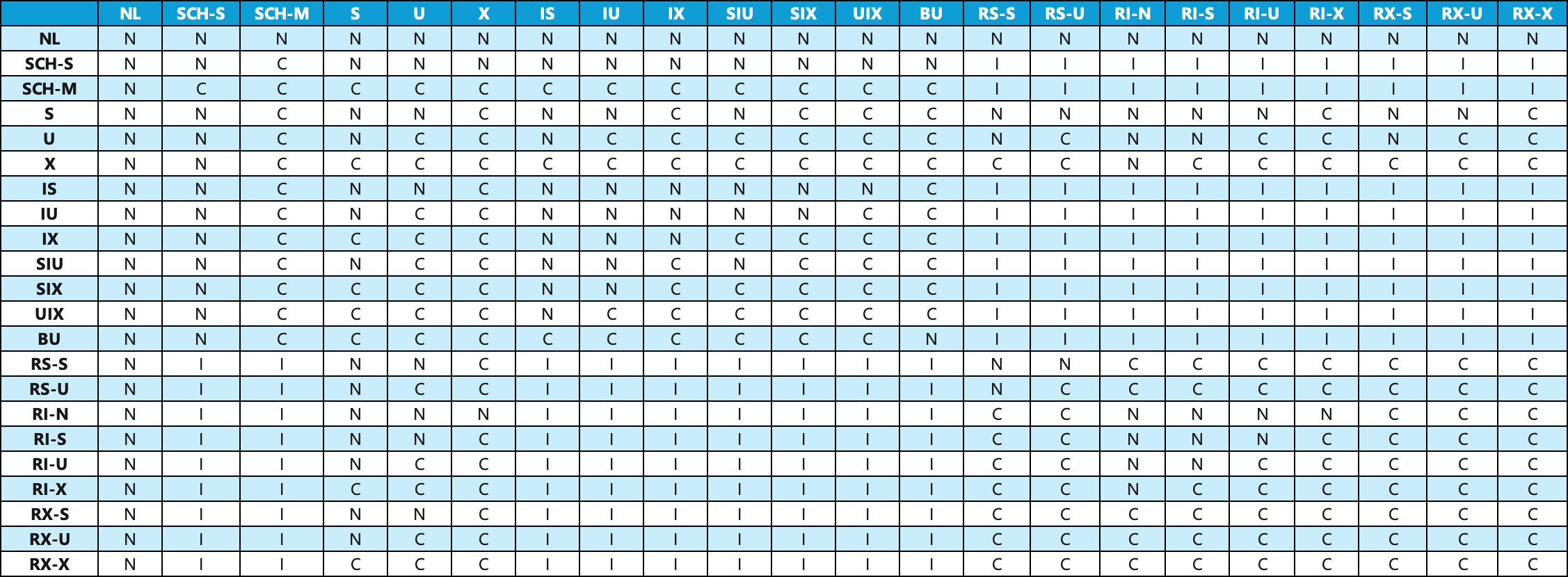

The following table shows the compatibility of the most commonly encountered lock modes.

| Existing granted mode | IS |

S |

U |

IX |

SIX |

X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requested mode | ||||||

Intent shared (IS) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Shared (S) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

Update (U) |

Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

Intent exclusive (IX) |

Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

Shared with intent exclusive (SIX) |

Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

Exclusive (X) |

No | No | No | No | No | No |

Note

An intent exclusive (IX) lock is compatible with an IX lock mode because IX means the intention is to update only some of the rows rather than all of them. Other transactions that attempt to read or update some of the rows are also permitted as long as they are not the same rows being updated by other transactions. Further, if two transactions attempt to update the same row, both transactions will be granted an IX lock at table and page level. However, one transaction will be granted an X lock at row level. The other transaction must wait until the row-level lock is removed.

Use the following table to determine the compatibility of all the lock modes available in the Database Engine.

| Key | Description |

|---|---|

| N | No conflict |

| I | Illegal |

| C | Conflict |

| NL | No lock |

| SCH-S | Schema stability lock |

| SCH-M | Schema modification lock |

| S | Shared |

| U | Update |

| X | Exclusive |

| IS | Intent shared |

| IU | Intent update |

| IX | Intent exclusive |

| SIU | Share with intent update |

| SIX | Share with intent exclusive |

| UIX | Update with intent exclusive |

| BU | Bulk update |

| RS-S | Shared range-shared |

| RS-U | Shared range-update |

| RI-N | Insert range-null |

| RI-S | Insert range-shared |

| RI-U | Insert range-update |

| RI-X | Insert range-exclusive |

| RX-S | Exclusive range-shared |

| RX-U | Exclusive range-update |

| RX-X | Exclusive range-exclusive |

Key-range locking

Key-range locks protect a range of rows implicitly included in a record set being read by a Transact-SQL statement while using the SERIALIZABLE transaction isolation level. The SERIALIZABLE isolation level requires that any query executed during a transaction must obtain the same set of rows every time it is executed during the transaction. A key range lock satisfies this requirement by preventing other transactions from inserting new rows whose keys would fall in the range of keys read by the SERIALIZABLE transaction.

Key-range locking prevents phantom reads. By protecting the ranges of keys between rows, it also prevents phantom insertions into a set of records accessed by a transaction.

A key-range lock is placed on an index, specifying a beginning and ending key value. This lock blocks any attempt to insert, update, or delete any row with a key value that falls in the range because those operations would first have to acquire a lock on the index. For example, a SERIALIZABLE transaction could issue a SELECT statement that reads all rows whose key values match the condition BETWEEN 'AAA' AND 'CZZ'. A key-range lock on the key values in the range from 'AAA' to 'CZZ' prevents other transactions from inserting rows with key values anywhere in that range, such as 'ADG', 'BBD', or 'CAL'.

Key-range lock modes

Key-range locks include both a range and a row component specified in range-row format:

- Range represents the lock mode protecting the range between two consecutive index entries.

- Row represents the lock mode protecting the index entry.

- Mode represents the combined lock mode used. Key-range lock modes consist of two parts. The first represents the type of lock used to lock the index range (RangeT) and the second represents the lock type used to lock a specific key (K). The two parts are connected with a hyphen (-), such as RangeT-K.

| Range | Row | Mode | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

RangeS |

S |

RangeS-S |

Shared range, shared resource lock; SERIALIZABLE range scan. |

RangeS |

U |

RangeS-U |

Shared range, update resource lock; SERIALIZABLE update scan. |

RangeI |

Null |

RangeI-N |

Insert range, null resource lock; used to test ranges before inserting a new key into an index. |

RangeX |

X |

RangeX-X |

Exclusive range, exclusive resource lock; used when updating a key in a range. |

Note

The internal Null lock mode is compatible with all other lock modes.

Key-range lock modes have a compatibility matrix that shows which locks are compatible with other locks obtained on overlapping keys and ranges.

| Existing granted mode | S |

U |

X |

RangeS-S |

RangeS-U |

RangeI-N |

RangeX-X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requested mode | |||||||

Shared (S) |

Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Update (U) |

Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Exclusive (X) |

No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

RangeS-S |

Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

RangeS-U |

Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

RangeI-N |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

RangeX-X |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Conversion locks

Conversion locks are created when a key-range lock overlaps another lock.

| Lock 1 | Lock 2 | Conversion lock |

|---|---|---|

S |

RangeI-N |

RangeI-S |

U |

RangeI-N |

RangeI-U |

X |

RangeI-N |

RangeI-X |

RangeI-N |

RangeS-S |

RangeX-S |

RangeI-N |

RangeS-U |

RangeX-U |

Conversion locks can be observed for a short period of time under different complex circumstances, sometimes while running concurrent processes.

Serializable range scan, singleton fetch, delete, and insert

Key-range locking ensures that the following operations are serializable:

- Range scan query

- Singleton fetch of nonexistent row

- Delete operation

- Insert operation

Before key-range locking can occur, the following conditions must be satisfied:

- The transaction-isolation level must be set to

SERIALIZABLE. - The query processor must use an index to implement the range filter predicate. For example, the

WHEREclause in aSELECTstatement could establish a range condition with this predicate:ColumnX BETWEEN N'AAA' AND N'CZZ'. A key-range lock can only be acquired ifColumnXis covered by an index key.

Examples

The following table and index are used as a basis for the key-range locking examples that follow.

Range scan query

To ensure a range scan query is serializable, the same query should return the same results each time it is executed within the same transaction. New rows must not be inserted within the range scan query by other transactions; otherwise, these become phantom inserts. For example, the following query uses the table and index in the previous illustration:

SELECT name

FROM mytable

WHERE name BETWEEN 'A' AND 'C';

Key-range locks are placed on the index entries corresponding to the range of rows where the name is between the values Adam and Dale, preventing new rows qualifying in the previous query from being added or deleted. Although the first name in this range is Adam, the RangeS-S mode key-range lock on this index entry ensures that no new names beginning with the letter A can be added before Adam, such as Abigail. Similarly, the RangeS-S key-range lock on the index entry for Dale ensures that no new names beginning with the letter C can be added after Carlos, such as Clive.

Note

The number of RangeS-S locks held is n+1, where n is the number of rows that satisfy the query.

Singleton fetch of nonexistent data

If a query within a transaction attempts to select a row that doesn't exist, issuing the query at a later point within the same transaction has to return the same result. No other transaction can be allowed to insert that nonexistent row. For example, given this query:

SELECT name

FROM mytable

WHERE name = 'Bill';

A key-range lock is placed on the index entry corresponding to the name range from Ben to Bing because the name Bill would be inserted between these two adjacent index entries. The RangeS-S mode key-range lock is placed on the index entry Bing. This prevents any other transaction from inserting values, such as Bill, between the index entries Ben and Bing.

Delete operation without optimized locking

When deleting a row within a transaction, the range the row falls into doesn't have to be locked for the duration of the transaction performing the delete operation. Locking the deleted key value until the end of the transaction is sufficient to maintain serializability. For example, given this DELETE statement:

DELETE mytable

WHERE name = 'Bob';

An exclusive (X) lock is placed on the index entry corresponding to the name Bob. Other transactions can insert or delete values before or after the row with the value Bob that is being deleted. However, any transaction that attempts to read, insert, or delete rows matching the value Bob will be blocked until the deleting transaction either commits or rolls back. (The READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT database option and the SNAPSHOT isolation level also allow reads from a row-version of the previously committed state.)

Range delete can be executed using three basic lock modes: row, page, or table lock. The row, page, or table locking strategy is decided by Query Optimizer or can be specified by the user through Query Optimizer hints such as ROWLOCK, PAGLOCK, or TABLOCK. When PAGLOCK or TABLOCK is used, the Database Engine immediately deallocates an index page if all rows are deleted from this page. In contrast, when ROWLOCK is used, all deleted rows are marked only as deleted; they are removed from the index page later using a background task.

Delete operation with optimized locking

When deleting a row within a transaction, the row and page locks are acquired and released incrementally, and not held for the duration of the transaction. For example, given this DELETE statement:

DELETE mytable

WHERE name = 'Bob';

A TID lock is placed on all the modified rows for the duration of the transaction. A lock is acquired on the TID of the index rows corresponding to the value Bob. With optimized locking, page and row locks continue to be acquired for updates, but each page and row lock is released as soon as each row is updated. The TID lock protects the rows from being updated until the transaction is complete. Any transaction that attempts to read, insert, or delete rows with the value Bob will be blocked until the deleting transaction either commits or rolls back. (The READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT database option and the SNAPSHOT isolation level also allow reads from a row-version of the previously committed state.)

Otherwise, the locking mechanics of a delete operation are the same as without optimized locking.

Insert operation without optimized locking

When inserting a row within a transaction, the range the row falls into doesn't have to be locked for the duration of the transaction performing the insert operation. Locking the inserted key value until the end of the transaction is sufficient to maintain serializability. For example, given this INSERT statement:

INSERT mytable VALUES ('Dan');

The RangeI-N mode key-range lock is placed on the index row corresponding to the name David to test the range. If the lock is granted, a row with the value Dan is inserted and an exclusive (X) lock is placed on the inserted row. The RangeI-N mode key-range lock is necessary only to test the range and isn't held for the duration of the transaction performing the insert operation. Other transactions can insert or delete values before or after the inserted row with the value Dan. However, any transaction attempting to read, insert, or delete the row with the value Dan will be blocked until the inserting transaction either commits or rolls back.

Insert operation with optimized locking

When inserting a row within a transaction, the range the row falls into doesn't have to be locked for the duration of the transaction performing the insert operation. Row and page locks are rarely acquired, only when there is an online index rebuild in progress, or when there are concurrent SERIALIZABLE transactions. If row and page locks are acquired, they are released quickly and not held for the duration of the transaction. Placing an exclusive TID lock on the inserted key value until the end of the transaction is sufficient to maintain serializability. For example, given this INSERT statement:

INSERT mytable VALUES ('Dan');

With optimized locking, a RangeI-N lock is only acquired if there at least one transaction that is using the SERIALIZABLE isolation level in the instance. The RangeI-N mode key-range lock is placed on the index row corresponding to the name David to test the range. If the lock is granted, a row with the value Dan is inserted and an exclusive (X) lock is placed on the inserted row. The RangeI-N mode key-range lock is necessary only to test the range and isn't held for the duration of the transaction performing the insert operation. Other transactions can insert or delete values before or after the inserted row with the value Dan. However, any transaction attempting to read, insert, or delete the row with the value Dan will be blocked until the inserting transaction either commits or rolls back.

Lock escalation

Lock escalation is the process of converting many fine-grained locks into fewer coarse-grain locks, reducing system overhead while increasing the probability of concurrency contention.

Lock escalation behaves differently depending on whether optimized locking is enabled.

Lock escalation without optimized locking

As the Database Engine acquires low-level locks, it also places intent locks on the objects that contain the lower-level objects:

- When locking rows or index key ranges, the Database Engine places an intent lock on the pages that contain the rows or keys.

- When locking pages, the Database Engine places an intent lock on the higher level objects that contain the pages. In addition to intent lock on the object, intent page locks are requested on the following objects:

- Leaf-level pages of nonclustered indexes

- Data pages of clustered indexes

- Heap data pages

The Database Engine might do both row and page locking for the same statement to minimize the number of locks and reduce the likelihood that lock escalation will be necessary. For example, the Database Engine could place page locks on a nonclustered index (if enough contiguous keys in the index node are selected to satisfy the query) and row locks on the clustered index or heap.

To escalate locks, the Database Engine attempts to change the intent lock on the table to the corresponding full lock, for example, changing an intent exclusive (IX) lock to an exclusive (X) lock, or an intent shared (IS) lock to a shared (S) lock. If the lock escalation attempt succeeds and the full table lock is acquired, then all HoBT, page (PAGE), or row-level (RID, KEY) locks held by the transaction on the heap or index are released. If the full lock cannot be acquired, no lock escalation happens at that time and the Database Engine will continue to acquire row, key, or page locks.

The Database Engine doesn't escalate row or key-range locks to page locks, but escalates them directly to table locks. Similarly, page locks are always escalated to table locks. Locking of partitioned tables can escalate to the HoBT level for the associated partition instead of to the table lock. A HoBT-level lock doesn't necessarily lock the aligned HoBTs for the partition.

Note

HoBT-level locks usually increase concurrency, but introduce the potential for deadlocks when transactions that are locking different partitions each want to expand their exclusive locks to the other partitions. In rare instances, TABLE locking granularity might perform better.

If a lock escalation attempt fails because of conflicting locks held by concurrent transactions, the Database Engine retries the lock escalation for each additional 1,250 locks acquired by the transaction.

Each escalation event operates primarily at the level of a single Transact-SQL statement. When the event starts, the Database Engine attempts to escalate all the locks owned by the current transaction in any of the tables that have been referenced by the active statement provided it meets the escalation threshold requirements. If the escalation event starts before the statement has accessed a table, no attempt is made to escalate the locks on that table. If lock escalation succeeds, any locks acquired by the transaction in a previous statement and still held at the time the event starts will be escalated if the table is referenced by the current statement and is included in the escalation event.

For example, assume that a session performs these operations:

- Begins a transaction.

- Updates

TableA. This generates exclusive row locks inTableAthat are held until the transaction completes. - Updates

TableB. This generates exclusive row locks inTableBthat are held until the transaction completes. - Performs a

SELECTthat joinsTableAwithTableC. The query execution plan calls for the rows to be retrieved fromTableAbefore the rows are retrieved fromTableC. - The

SELECTstatement triggers lock escalation while it is retrieving rows fromTableAand before it has accessedTableC.

If lock escalation succeeds, only the locks held by the session on TableA are escalated. This includes both the shared locks from the SELECT statement and the exclusive locks from the previous UPDATE statement. While only the locks the session acquired in TableA for the SELECT statement are counted to determine if lock escalation should be done, once escalation is successful all locks held by the session in TableA are escalated to an exclusive lock on the table, and all other lower-granularity locks, including intent locks, on TableA are released.

No attempt is made to escalate locks on TableB because there was no active reference to TableB in the SELECT statement. Similarly no attempt is made to escalate the locks on TableC, which are not escalated because it had not yet been accessed when the escalation occurred.

Lock escalation with optimized locking

Optimized locking helps to reduce lock memory as very few locks are held for the duration of the transaction. As the Database Engine acquires row and page locks, lock escalation can occur similarly, but far less frequently. Optimized locking typically succeeds in avoiding lock escalations, lowering the number of locks and amount of lock memory necessary.

When optimized locking is enabled, and in the default READ COMMITTED isolation level, the Database Engine releases row and page locks as soon as the row is modified. No row and page locks are held for the duration of the transaction, except for a single Transaction ID (TID) lock. This reduces the likelihood of lock escalation.

Lock escalation thresholds

Lock escalation is triggered when lock escalation isn't disabled on the table by using the ALTER TABLE SET LOCK_ESCALATION option, and when either of the following conditions exists:

- A single Transact-SQL statement acquires at least 5,000 locks on a single nonpartitioned table or index.

- A single Transact-SQL statement acquires at least 5,000 locks on a single partition of a partitioned table and the

ALTER TABLE SET LOCK_ESCALATIONoption is set to AUTO. - The number of locks in an instance of the Database Engine exceeds memory or configuration thresholds.

If locks cannot be escalated because of lock conflicts, the Database Engine periodically triggers lock escalation at every 1,250 new locks acquired.

Escalation threshold for a Transact-SQL statement

When the Database Engine checks for possible escalations at every 1,250 newly acquired locks, a lock escalation will occur if and only if a Transact-SQL statement has acquired at least 5,000 locks on a single reference of a table. Lock escalation is triggered when a Transact-SQL statement acquires at least 5,000 locks on a single reference of a table. For example, lock escalation isn't triggered if a statement acquires 3,000 locks in one index and 3,000 locks in another index of the same table. Similarly, lock escalation isn't triggered if a statement has a self join on a table, and each reference to the table only acquires 3,000 locks in the table.

Lock escalation only occurs for tables that have been accessed at the time the escalation is triggered. Assume that a single SELECT statement is a join that accesses three tables in this sequence: TableA, TableB, and TableC. The statement acquires 3,000 row locks in the clustered index for TableA and at least 5,000 row locks in the clustered index for TableB, but hasn't yet accessed TableC. When the Database Engine detects that the statement has acquired at least 5,000 row locks in TableB, it attempts to escalate all locks held by the current transaction on TableB. It also attempts to escalate all locks held by the current transaction on TableA, but since the number of locks on TableA is less than 5,000, the escalation will not succeed. No lock escalation is attempted for TableC because it had not yet been accessed when the escalation occurred.

Escalation threshold for an instance of the Database Engine

Whenever the number of locks is greater than the memory threshold for lock escalation, the Database Engine triggers lock escalation. The memory threshold depends on the setting of the locks configuration option:

If the

locksoption is set to its default setting of 0, then the lock escalation threshold is reached when the memory used by lock objects is 24 percent of the memory used by the Database Engine, excluding AWE memory. The data structure used to represent a lock is approximately 100 bytes long. This threshold is dynamic because the Database Engine dynamically acquires and frees memory to adjust for varying workloads.If the

locksoption is a value other than 0, then the lock escalation threshold is 40 percent (or less if there is a memory pressure) of the value of the locks option.

The Database Engine can choose any active statement from any session for escalation, and for every 1,250 new locks it will choose statements for escalation as long as the lock memory used in the instance remains above the threshold.

Lock escalation with mixed lock types

When lock escalation occurs, the lock selected for the heap or index is strong enough to meet the requirements of the most restrictive lower level lock.

For example, assume a session:

- Begins a transaction.

- Updates a table containing a clustered index.

- Issues a

SELECTstatement that references the same table.

The UPDATE statement acquires these locks:

- Exclusive (

X) locks on the updated data rows. - Intent exclusive (

IX) locks on the clustered index pages containing those rows. - An

IXlock on the clustered index and another on the table.

The SELECT statement acquires these locks:

- Shared (

S) locks on all data rows it reads, unless the row is already protected by anXlock from theUPDATEstatement. - Intent Shared (

IS) locks on all clustered index pages containing those rows, unless the page is already protected by anIXlock. - No lock on the clustered index or table because they are already protected by

IXlocks.

If the SELECT statement acquires enough locks to trigger lock escalation and the escalation succeeds, the IX lock on the table is converted to an X lock, and all the row, page, and index locks are released. Both the updates and reads are protected by the X lock on the table.

Reduce locking and lock escalation

In most cases, the Database Engine delivers the best performance when operating with its default settings for locking and lock escalation.

Take advantage of optimized locking.

- Optimized locking offers an improved transaction locking mechanism that reduces lock memory consumption and blocking for concurrent transactions. Lock escalation is far less likely to ever occur when optimized locking is enabled.

- Avoid using table hints with optimized locking. Table hints may reduce the effectiveness of optimized locking.

- Enable the READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT option for the database for the most benefit from optimized locking. This is the default in Azure SQL Database.

- Optimized locking requires accelerated database recovery (ADR) to be enabled on the database.

If an instance of the Database Engine generates a lot of locks and is seeing frequent lock escalations, consider reducing the amount of locking with the following strategies:

Use an isolation level that doesn't generate shared locks for read operations:

READ COMMITTEDisolation level when theREAD_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOTdatabase option isON.SNAPSHOTisolation level.READ UNCOMMITTEDisolation level. This can only be used for systems that can operate with dirty reads.

Use the

PAGLOCKorTABLOCKtable hints to have the Database Engine use page, heap, or index locks instead of low-level locks. Using this option, however, increases the problems of users blocking other users attempting to access the same data and should not be used in systems with more than a few concurrent users.If optimized locking isn't available, for partitioned tables, use the

LOCK_ESCALATIONoption of ALTER TABLE to escalate locks to the partition instead of the table, or to disable lock escalation for a table.Break up large batch operations into several smaller operations. For example, suppose you ran the following query to remove several hundred thousand old rows from an audit table, and then you found that it caused a lock escalation that blocked other users:

DELETE FROM LogMessages WHERE LogDate < '2024-09-26'By removing these rows a few hundred at a time, you can dramatically reduce the number of locks that accumulate per transaction and prevent lock escalation. For example: