RAG chunking phase

After you gather your test documents and queries and perform a document analysis during the preparation phase, the next phase is chunking. Breaking down documents into appropriately sized chunks that each contain semantically relevant content is crucial for the success of your Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) implementation. Passing entire documents or oversized chunks is expensive, might overwhelm the token limits of the model, and doesn't produce the best results. Passing information to a language model that's irrelevant to the query can result in inaccurate or unrelated responses. You need to optimize the process of passing relevant information and removing irrelevant information by using effective chunking and searching strategies. This approach minimizes false positives and false negatives, and maximizes true positives and true negatives.

Chunks that are too small and don't contain sufficient context to address the query can result in poor outcomes. Relevant context that exists across multiple chunks might not be captured. The key is to implement effective chunking approaches for your specific document types and their specific structures and content. There are various chunking approaches to consider, each with their own cost implications and effectiveness, depending on the type and structure of document that they're applied to.

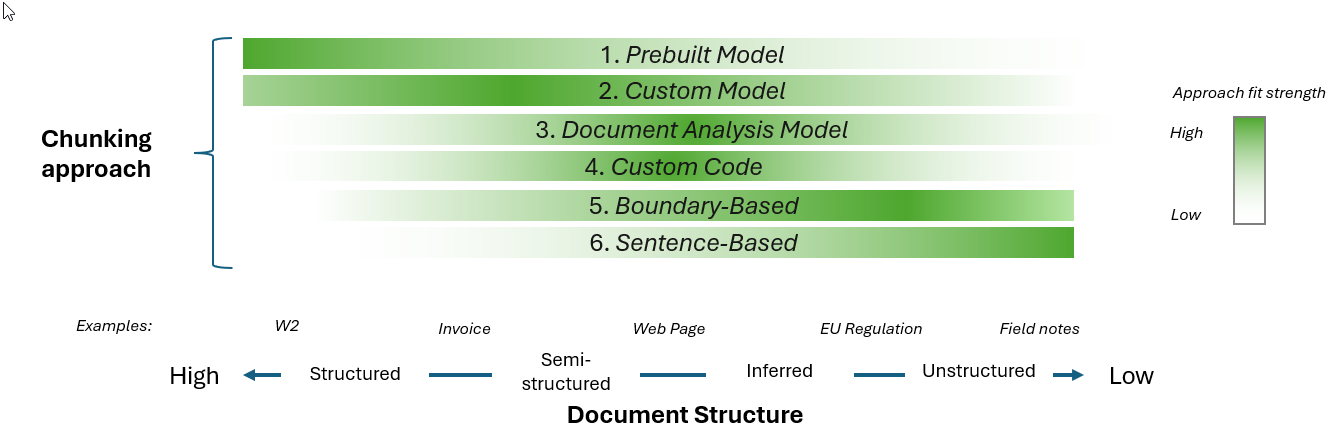

This article describes various chunking approaches and examines how the structure of your documents can influence the chunking approach that you choose.

This article is part of a series. Read the introduction before you continue.

Chunking economics

When you determine your overall chunking strategy, you must consider your budget and your quality and throughput requirements for your document collection. There are engineering costs for the design and implementation of each unique chunking implementation and per-document processing costs that differ depending on the approach. If your documents have embedded or linked media, you must consider the economics of processing those elements. For chunking, this processing generally uses language models to generate descriptions of the media. Those descriptions are then chunked. An alternative approach for some media is to pass them as-is to a multi-modal model at inferencing time. However, this approach doesn't affect the chunking economics.

The following sections examine the economics of chunking images and the overall solution.

Image chunking economics

There's a cost to use a language model to generate a description of an image that you chunk. For example, cloud-based services such as Azure OpenAI Service either charge on a per-transaction basis or on a prepaid provisioning basis. Larger images incur a larger cost. Through your document analysis, you should determine which images are valuable to chunk and which images you should ignore. From there, you need to understand the number and sizes of the images in your solution. Then you should weigh the value of chunking the image descriptions against the cost to generate those descriptions.

One way to determine which images to process is to use a service such as Azure AI Vision to classify images, tag images, or do logo detection. You can then use the results and confidence indicators to determine whether the image adds meaningful, contextual value and should be processed. Calls to Vision might be less expensive than calls to language models, so this approach could result in cost savings. Experiment to determine what confidence levels and what classifications or tags provide the best results for your data. Another option is to build your own classifier model. If you take this approach, make sure to consider the costs to build, host, and maintain your own model.

Another cost optimization strategy is to cache by using the Cache-Aside pattern. You can generate a key that's based on the hash of the image. As a first step, check to see if you have a cached result from a prior run or previously processed document. If you do, you can use that result. This approach eliminates the costs of calling a classifier or a language model. If there's no cache, when you call to the classifier or language model, you cache the result. Future calls for this image use the cache.

The following simple workflow integrates all of these cost optimization processes:

Check to see if the image processing is cached. If so, use the cached results.

Run your classifier to determine whether you should process the image. Cache the classification result. If your classification logic determines that the image adds value, proceed to the next step.

Generate the description for your image. Cache the result.

Economics of the overall solution

Consider the following factors when you assess the cost of your overall solution:

Number of unique chunking implementations: Each unique implementation has engineering and maintenance costs. Make sure to consider the number of unique document types in your collection and the cost versus quality trade-offs of unique implementations for each.

Per-document cost of each implementation: Some chunking approaches might result in better quality chunks but have a higher financial and temporal cost to generate those chunks. For example, using a prebuilt model in Azure AI Document Intelligence likely has a higher per-document cost than a pure text parsing implementation, but might result in better chunks.

Number of initial documents: The number of initial documents that you need to process to launch your solution.

Number of incremental documents: The number and rate of new documents that you must process for ongoing maintenance of the system.

Loading and chunking

During chunking, you must first load the document into memory in some format. The chunking code then operates against the in-memory representation of the document. You can combine the loading code with chunking, or separate loading into its own phase. The approach that you choose should mostly be based on architectural constraints and your preferences. The following sections briefly explore both options and provide general recommendations.

Separate loading and chunking

There are several reasons why you might choose to separate the loading and chunking phases. You might want to encapsulate logic in the loading code. You might want to persist the result of the loading code before chunking, especially when you experiment with various chunking permutations to save on processing time or cost. Lastly, you might want to run the loading and chunking code in separate processes for architectural reasons such as process bulkheading or security segmentation that involves removing personal data.

Encapsulate logic in the loading code

You might choose to encapsulate preprocessing logic in the loading phase. This approach simplifies the chunking code because it doesn't require any preprocessing. Preprocessing can be as simple as removing or annotating parts of the document that you want to ignore in document analysis, such as watermarks, headers, and footers, to more complex tasks such as reformatting the document. For example, you can include the following preprocessing tasks in the loading phase:

Remove or annotate items that you want to ignore.

Replace image references with image descriptions. During this phase, you use a large language model to generate a description for the image and update the document with that description. If you determine in the document analysis phase that there's surrounding text that provides valuable context to the image, then pass that text, along with the image, to the large language model.

Download or copy images to file storage like Azure Data Lake Storage to be processed separately from the document text. If you determine in the document analysis that there's surrounding text that provides valuable context to the image, store this text along with the image in file storage.

Reformat tables so that they're more easily processed.

Persist the result of the loading code

There are multiple reasons that you might choose to persist the result of the loading code. One reason is if you want the ability to inspect the documents after they're loaded and preprocessed, but before the chunking logic is run. Another reason is that you might want to run different chunking logic against the same preprocessed code while it's in development or in production. Persisting the loaded code speeds up this process.

Run loading and chunking code in separate processes

Separate the loading and chunking code into separate processes to help run multiple chunking implementations against the same preprocessed code. This separation also allows you to run loading and chunking code in different compute environments and on different hardware. You can use this design to independently scale the compute that's used for loading and chunking.

Combine loading and chunking

Combining the loading and chunking code is a simpler implementation in most cases. Many of the operations that you might consider doing in preprocessing in a separate loading phase can be accomplished in the chunking phase. For example, instead of replacing image URLs with a description in the loading phase, the chunking logic can make calls to the large language model to get a text description and chunk the description.

When you have document formats like HTML that have tags with references to images, ensure that the reader or parser that the chunking code is using doesn't strip out the tags. The chunking code needs to be able to identify image references.

Recommendations

Consider the following recommendations when you determine whether you should combine or separate your chunking logic.

Start by combining loading and chunking logic. Separate them when your solution requires it.

Avoid converting documents to an intermediate format if you choose to separate the processes. This type of operation can result in data loss.

Chunking approaches

This section provides an overview of common chunking approaches. You can use multiple approaches in implementation, such as combining the use of a language model to get a text representation of an image with many of the listed approaches.

Each approach is accompanied by a summarized decision-making matrix that highlights the tools, associated costs, and more. The engineering effort and processing costs are subjective and are included for relative comparison.

Sentence-based parsing

This straightforward approach breaks down text documents into chunks that are composed of complete sentences. The advantages of this approach include its low implementation cost, low processing cost, and its applicability to any text-based document that's written in prose or full sentences. One drawback of this approach is that each chunk might not capture the full context of an idea or meaning. Multiple sentences must often be taken together to capture the semantic meaning.

Tools: spaCy sentence tokenizer, LangChain recursive text splitter, NLTK sentence tokenizer

Engineering effort: Low

Processing cost: Low

Use cases: Unstructured documents written in prose or full sentences, and your collection of documents contains a prohibitive number of different document types that require individual chunking strategies

Examples: User-generated content like open-ended feedback from surveys, forum posts, reviews, email messages, a novel, or an essay

Fixed-size parsing, with overlap

This approach breaks down a document into chunks based on a fixed number of characters or tokens and allows for some overlap of characters between chunks. This approach has many of the same advantages and disadvantages as sentence-based parsing. One advantage of this approach over sentence-based parsing is the ability to obtain chunks with semantic meanings that span multiple sentences.

You must choose the fixed size of the chunks and the amount of overlap. Because the results vary for different document types, it's best to use a tool like the Hugging Face chunk visualizer to do exploratory analysis. You can use tools like this to visualize how your documents are chunked based on your decisions. You should use BERT tokens instead of character counts when you use fixed-sized parsing. BERT tokens are based on meaningful units of language, so they preserve more semantic information than character counts.

Tools: LangChain recursive text splitter, Hugging Face chunk visualizer

Engineering effort: Low

Processing cost: Low

Use cases: Unstructured documents written in prose or non-prose with complete or incomplete sentences. Your collection of documents contains a prohibitive number of different document types that require individual chunking strategies

Examples: User-generated content like open-ended feedback from surveys, forum posts, reviews, email messages, personal notes, research notes, lists

Custom code

This approach parses documents by using custom code to create chunks. This approach is most successful for text-based documents where the structure is known or can be inferred and a high degree of control over chunk creation is required. You can use text parsing techniques like regular expressions to create chunks based on patterns within the document's structure. The goal is to create chunks that have similar size in length and chunks that have distinct content. Many programming languages provide support for regular expressions, and some have libraries or packages that provide more elegant string manipulation features.

Tools: Python (re, regex, BeautifulSoup, lxml, html5lib, marko), R (stringr, xml2), Julia (Gumbo.jl)

Engineering effort: Medium

Processing cost: Low

Use cases: Semi-structured documents where structure can be inferred

Examples: Patent filings, research papers, insurance policies, scripts, and screenplays

Language model augmentation

You can use language models to create chunks. For example, you can use a large language model, such as GPT-4, to generate textual representations of images or summaries of tables that can be used as chunks. Language model augmentation is used with other chunking approaches such as custom code.

If your document analysis determines that the text before or after the image helps answer some requirement questions, pass this extra context to the language model. It's important to experiment to determine whether this extra context improves the performance of your solution.

If your chunking logic splits the image description into multiple chunks, make sure that you include the image URL in each chunk. Include the image URL in each chunk to ensure that metadata is returned for all queries that the image serves. This step is crucial for scenarios where the end user needs to access the source image through that URL or use raw images during inferencing time.

Tools: Azure OpenAI, OpenAI

Engineering effort: Medium

Processing cost: High

Use cases: Images, tables

Examples: Generate text representations of tables and images, summarize transcripts from meetings, speeches, interviews, or podcasts

Document layout analysis

Document layout analysis libraries and services combine optical character recognition capabilities with deep learning models to extract both the structure and text of documents. Structural elements can include headers, footers, titles, section headings, tables, and figures. The goal is to provide better semantic meaning to content that's contained in documents.

Document layout analysis libraries and services expose a model that represents the structural and textual content of the document. You still have to write code that interacts with the model.

Note

Document Intelligence is a cloud-based service that requires you to upload your document. You need to ensure that your security and compliance regulations allow you to upload documents to such services.

Tools: Document Intelligence document analysis models, Donut, Layout Parser

Engineering effort: Medium

Processing cost: Medium

Use cases: Semi-structured documents

Examples: News articles, web pages, resumes

Prebuilt model

Services such as Document Intelligence provide prebuilt models that you can take advantage of for various document types. Some models are trained for specific document types, such as the U.S. W-2 tax form, while others target a broader genre of document types such as invoices.

Tools: Document Intelligence prebuilt models, Power Automate intelligent document processing, LayoutLMv3

Engineering effort: Low

Processing cost: Medium/High

Use cases: Structured documents where a prebuilt model exists

Specific examples: Invoices, receipts, health insurance cards, W-2 forms

Custom model

For highly structured documents where no prebuilt model exists, you might have to build a custom model. This approach can be effective for images or documents that are highly structured, which makes using text parsing techniques difficult.

Tools: Document Intelligence custom models, Tesseract

Engineering effort: High

Processing cost: Medium/High

Use cases: Structured documents where a prebuilt model doesn't exist

Examples: Automotive repair and maintenance schedules, academic transcripts, records, technical manuals, operational procedures, maintenance guidelines

Document structure

Documents vary in the amount of structure that they have. Some documents, like government forms, have a complex and well-known structure, such as a U.S. W-2 tax form. At the other end of the spectrum are unstructured documents like free-form notes. The degree of structure to a document type is a good starting point to determine an effective chunking approach. While there are no specific rules, this section provides you with some guidelines to follow.

Structured documents

Structured documents, sometimes referred to as fixed-format documents, have defined layouts. The data in these documents is located at fixed locations. For example, the date, or customer family name, is found in the same location in every document of the same fixed format. An example of a fixed-format document is the U.S. W-2 tax document.

Fixed-format documents might be scanned images of original documents that were hand-filled or have complex layout structures. This format makes them difficult to process by using a basic text parsing approach. A typical approach to processing complex document structures is to use machine learning models to extract data and apply semantic meaning to that data, when possible.

Examples: W-2 form, insurance card

Typical approaches: Prebuilt models, custom models

Semi-structured documents

Semi-structured documents don't have a fixed format or schema, like the W-2 form, but they do provide consistency regarding format or schema. For example, all invoices aren't laid out the same. However, they generally have a consistent schema. You can expect an invoice to have an invoice number and some form of bill to and ship to name and address, among other data. A web page might not have schema consistencies, but they do have similar structural or layout elements, such as body, title, H1, and p that can add semantic meaning to the surrounding text.

Like structured documents, semi-structured documents that have complex layout structures are difficult to process by using text parsing. For these document types, machine learning models are a good approach. There are prebuilt models for certain domains that have consistent schemas like invoices, contracts, or health insurance documents. Consider building custom models for complex structures where no prebuilt model exists.

Examples: Invoices, receipts, web pages, markdown files

Typical approaches: Document analysis models

Inferred structure

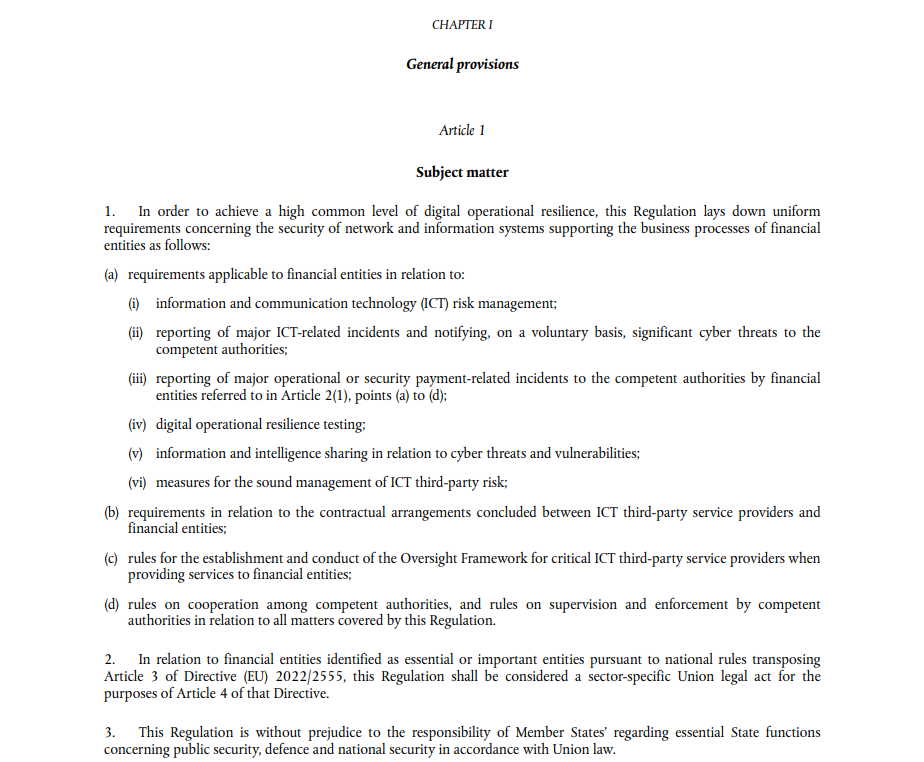

Some documents have a structure but aren't written in markup. For these documents, the structure must be inferred. A good example is the following EU regulation document.

Because you can clearly understand the structure of the document, and there are no known models for it, you can determine that you can write custom code. A document format such as this might not warrant the effort to create a custom model, depending on the number of different documents of this type that you're working with. For example, if your collection contains all EU regulations or U.S. state laws, a custom model might be a good approach. If you're working with a single document, like the EU regulation in the example, custom code might be more cost effective.

Examples: Law documents, scripts, manufacturing specifications

Typical approaches: Custom code, custom models

Unstructured documents

A good approach for documents that have little to no structure are sentence-based or fixed-size with overlap approaches.

Examples: User-generated content like open-ended feedback from surveys, forum posts, reviews, email messages, personal notes, research notes

Typical approaches: Sentence-based or boundary-based with overlap

Experimentation

This article describes the most suitable chunking approaches for each document type, but in practice, any of the approaches might be appropriate for any document type. For example, sentence-based parsing might be appropriate for highly structured documents, or a custom model might be appropriate for unstructured documents. Part of optimizing your RAG solution is to experiment with various chunking approaches. Consider the number of resources that you have, the technical skill of your resources, and the volume of documents that you have to process. To achieve an optimal chunking strategy, observe the advantages and trade-offs of each approach that you test to ensure that you choose the appropriate approach for your use case.