Exercício - Estimar recursos para um problema do mundo real

O algoritmo de factoring de Shor é um dos algoritmos quânticos mais conhecidos. Ele oferece uma aceleração exponencial sobre qualquer algoritmo de fatoração clássico conhecido.

A criptografia clássica usa meios físicos ou matemáticos, como dificuldade computacional, para realizar uma tarefa. Um protocolo criptográfico popular é o esquema Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA), que se baseia na suposição da dificuldade de fatoração de números primos usando um computador clássico.

O algoritmo de Shor implica que computadores quânticos suficientemente grandes podem quebrar a criptografia de chave pública. Estimar os recursos necessários para o algoritmo de Shor é importante para avaliar a vulnerabilidade desses tipos de esquemas criptográficos.

No exercício a seguir, você calculará as estimativas de recursos para a fatoração de um inteiro de 2.048 bits. Para este aplicativo, você calculará as estimativas de recursos físicos diretamente a partir de estimativas de recursos lógicos pré-computados. Para o orçamento de erro tolerado, você usará $\epsilon = 1/3$.

Escreva o algoritmo do Shor

No Visual Studio Code, selecione View > Command palette e selecione Create: New Jupyter Notebook.

Salve o bloco de anotações como ShorRE.ipynb.

Na primeira célula, importe o

qsharppacote:import qsharpUse o

Microsoft.Quantum.ResourceEstimationnamespace para definir uma versão otimizada em cache do algoritmo de fatoração de inteiros do Shor. Adicione uma nova célula e copie e cole o seguinte código:%%qsharp open Microsoft.Quantum.Arrays; open Microsoft.Quantum.Canon; open Microsoft.Quantum.Convert; open Microsoft.Quantum.Diagnostics; open Microsoft.Quantum.Intrinsic; open Microsoft.Quantum.Math; open Microsoft.Quantum.Measurement; open Microsoft.Quantum.Unstable.Arithmetic; open Microsoft.Quantum.ResourceEstimation; operation RunProgram() : Unit { let bitsize = 31; // When choosing parameters for `EstimateFrequency`, make sure that // generator and modules are not co-prime let _ = EstimateFrequency(11, 2^bitsize - 1, bitsize); } // In this sample we concentrate on costing the `EstimateFrequency` // operation, which is the core quantum operation in Shors algorithm, and // we omit the classical pre- and post-processing. /// # Summary /// Estimates the frequency of a generator /// in the residue ring Z mod `modulus`. /// /// # Input /// ## generator /// The unsigned integer multiplicative order (period) /// of which is being estimated. Must be co-prime to `modulus`. /// ## modulus /// The modulus which defines the residue ring Z mod `modulus` /// in which the multiplicative order of `generator` is being estimated. /// ## bitsize /// Number of bits needed to represent the modulus. /// /// # Output /// The numerator k of dyadic fraction k/2^bitsPrecision /// approximating s/r. operation EstimateFrequency( generator : Int, modulus : Int, bitsize : Int ) : Int { mutable frequencyEstimate = 0; let bitsPrecision = 2 * bitsize + 1; // Allocate qubits for the superposition of eigenstates of // the oracle that is used in period finding. use eigenstateRegister = Qubit[bitsize]; // Initialize eigenstateRegister to 1, which is a superposition of // the eigenstates we are estimating the phases of. // We first interpret the register as encoding an unsigned integer // in little endian encoding. ApplyXorInPlace(1, eigenstateRegister); let oracle = ApplyOrderFindingOracle(generator, modulus, _, _); // Use phase estimation with a semiclassical Fourier transform to // estimate the frequency. use c = Qubit(); for idx in bitsPrecision - 1..-1..0 { within { H(c); } apply { // `BeginEstimateCaching` and `EndEstimateCaching` are the operations // exposed by Azure Quantum Resource Estimator. These will instruct // resource counting such that the if-block will be executed // only once, its resources will be cached, and appended in // every other iteration. if BeginEstimateCaching("ControlledOracle", SingleVariant()) { Controlled oracle([c], (1 <<< idx, eigenstateRegister)); EndEstimateCaching(); } R1Frac(frequencyEstimate, bitsPrecision - 1 - idx, c); } if MResetZ(c) == One { set frequencyEstimate += 1 <<< (bitsPrecision - 1 - idx); } } // Return all the qubits used for oracles eigenstate back to 0 state // using Microsoft.Quantum.Intrinsic.ResetAll. ResetAll(eigenstateRegister); return frequencyEstimate; } /// # Summary /// Interprets `target` as encoding unsigned little-endian integer k /// and performs transformation |k⟩ ↦ |gᵖ⋅k mod N ⟩ where /// p is `power`, g is `generator` and N is `modulus`. /// /// # Input /// ## generator /// The unsigned integer multiplicative order ( period ) /// of which is being estimated. Must be co-prime to `modulus`. /// ## modulus /// The modulus which defines the residue ring Z mod `modulus` /// in which the multiplicative order of `generator` is being estimated. /// ## power /// Power of `generator` by which `target` is multiplied. /// ## target /// Register interpreted as LittleEndian which is multiplied by /// given power of the generator. The multiplication is performed modulo /// `modulus`. internal operation ApplyOrderFindingOracle( generator : Int, modulus : Int, power : Int, target : Qubit[] ) : Unit is Adj + Ctl { // The oracle we use for order finding implements |x⟩ ↦ |x⋅a mod N⟩. We // also use `ExpModI` to compute a by which x must be multiplied. Also // note that we interpret target as unsigned integer in little-endian // encoding by using the `LittleEndian` type. ModularMultiplyByConstant(modulus, ExpModI(generator, power, modulus), target); } /// # Summary /// Performs modular in-place multiplication by a classical constant. /// /// # Description /// Given the classical constants `c` and `modulus`, and an input /// quantum register (as LittleEndian) |𝑦⟩, this operation /// computes `(c*x) % modulus` into |𝑦⟩. /// /// # Input /// ## modulus /// Modulus to use for modular multiplication /// ## c /// Constant by which to multiply |𝑦⟩ /// ## y /// Quantum register of target internal operation ModularMultiplyByConstant(modulus : Int, c : Int, y : Qubit[]) : Unit is Adj + Ctl { use qs = Qubit[Length(y)]; for (idx, yq) in Enumerated(y) { let shiftedC = (c <<< idx) % modulus; Controlled ModularAddConstant([yq], (modulus, shiftedC, qs)); } ApplyToEachCA(SWAP, Zipped(y, qs)); let invC = InverseModI(c, modulus); for (idx, yq) in Enumerated(y) { let shiftedC = (invC <<< idx) % modulus; Controlled ModularAddConstant([yq], (modulus, modulus - shiftedC, qs)); } } /// # Summary /// Performs modular in-place addition of a classical constant into a /// quantum register. /// /// # Description /// Given the classical constants `c` and `modulus`, and an input /// quantum register (as LittleEndian) |𝑦⟩, this operation /// computes `(x+c) % modulus` into |𝑦⟩. /// /// # Input /// ## modulus /// Modulus to use for modular addition /// ## c /// Constant to add to |𝑦⟩ /// ## y /// Quantum register of target internal operation ModularAddConstant(modulus : Int, c : Int, y : Qubit[]) : Unit is Adj + Ctl { body (...) { Controlled ModularAddConstant([], (modulus, c, y)); } controlled (ctrls, ...) { // We apply a custom strategy to control this operation instead of // letting the compiler create the controlled variant for us in which // the `Controlled` functor would be distributed over each operation // in the body. // // Here we can use some scratch memory to save ensure that at most one // control qubit is used for costly operations such as `AddConstant` // and `CompareGreaterThenOrEqualConstant`. if Length(ctrls) >= 2 { use control = Qubit(); within { Controlled X(ctrls, control); } apply { Controlled ModularAddConstant([control], (modulus, c, y)); } } else { use carry = Qubit(); Controlled AddConstant(ctrls, (c, y + [carry])); Controlled Adjoint AddConstant(ctrls, (modulus, y + [carry])); Controlled AddConstant([carry], (modulus, y)); Controlled CompareGreaterThanOrEqualConstant(ctrls, (c, y, carry)); } } } /// # Summary /// Performs in-place addition of a constant into a quantum register. /// /// # Description /// Given a non-empty quantum register |𝑦⟩ of length 𝑛+1 and a positive /// constant 𝑐 < 2ⁿ, computes |𝑦 + c⟩ into |𝑦⟩. /// /// # Input /// ## c /// Constant number to add to |𝑦⟩. /// ## y /// Quantum register of second summand and target; must not be empty. internal operation AddConstant(c : Int, y : Qubit[]) : Unit is Adj + Ctl { // We are using this version instead of the library version that is based // on Fourier angles to show an advantage of sparse simulation in this sample. let n = Length(y); Fact(n > 0, "Bit width must be at least 1"); Fact(c >= 0, "constant must not be negative"); Fact(c < 2 ^ n, $"constant must be smaller than {2L ^ n}"); if c != 0 { // If c has j trailing zeroes than the j least significant bits // of y will not be affected by the addition and can therefore be // ignored by applying the addition only to the other qubits and // shifting c accordingly. let j = NTrailingZeroes(c); use x = Qubit[n - j]; within { ApplyXorInPlace(c >>> j, x); } apply { IncByLE(x, y[j...]); } } } /// # Summary /// Performs greater-than-or-equals comparison to a constant. /// /// # Description /// Toggles output qubit `target` if and only if input register `x` /// is greater than or equal to `c`. /// /// # Input /// ## c /// Constant value for comparison. /// ## x /// Quantum register to compare against. /// ## target /// Target qubit for comparison result. /// /// # Reference /// This construction is described in [Lemma 3, arXiv:2201.10200] internal operation CompareGreaterThanOrEqualConstant(c : Int, x : Qubit[], target : Qubit) : Unit is Adj+Ctl { let bitWidth = Length(x); if c == 0 { X(target); } elif c >= 2 ^ bitWidth { // do nothing } elif c == 2 ^ (bitWidth - 1) { ApplyLowTCNOT(Tail(x), target); } else { // normalize constant let l = NTrailingZeroes(c); let cNormalized = c >>> l; let xNormalized = x[l...]; let bitWidthNormalized = Length(xNormalized); let gates = Rest(IntAsBoolArray(cNormalized, bitWidthNormalized)); use qs = Qubit[bitWidthNormalized - 1]; let cs1 = [Head(xNormalized)] + Most(qs); let cs2 = Rest(xNormalized); within { for i in IndexRange(gates) { (gates[i] ? ApplyAnd | ApplyOr)(cs1[i], cs2[i], qs[i]); } } apply { ApplyLowTCNOT(Tail(qs), target); } } } /// # Summary /// Internal operation used in the implementation of GreaterThanOrEqualConstant. internal operation ApplyOr(control1 : Qubit, control2 : Qubit, target : Qubit) : Unit is Adj { within { ApplyToEachA(X, [control1, control2]); } apply { ApplyAnd(control1, control2, target); X(target); } } internal operation ApplyAnd(control1 : Qubit, control2 : Qubit, target : Qubit) : Unit is Adj { body (...) { CCNOT(control1, control2, target); } adjoint (...) { H(target); if (M(target) == One) { X(target); CZ(control1, control2); } } } /// # Summary /// Returns the number of trailing zeroes of a number /// /// ## Example /// ```qsharp /// let zeroes = NTrailingZeroes(21); // = NTrailingZeroes(0b1101) = 0 /// let zeroes = NTrailingZeroes(20); // = NTrailingZeroes(0b1100) = 2 /// ``` internal function NTrailingZeroes(number : Int) : Int { mutable nZeroes = 0; mutable copy = number; while (copy % 2 == 0) { set nZeroes += 1; set copy /= 2; } return nZeroes; } /// # Summary /// An implementation for `CNOT` that when controlled using a single control uses /// a helper qubit and uses `ApplyAnd` to reduce the T-count to 4 instead of 7. internal operation ApplyLowTCNOT(a : Qubit, b : Qubit) : Unit is Adj+Ctl { body (...) { CNOT(a, b); } adjoint self; controlled (ctls, ...) { // In this application this operation is used in a way that // it is controlled by at most one qubit. Fact(Length(ctls) <= 1, "At most one control line allowed"); if IsEmpty(ctls) { CNOT(a, b); } else { use q = Qubit(); within { ApplyAnd(Head(ctls), a, q); } apply { CNOT(q, b); } } } controlled adjoint self; }

Estimar o algoritmo de Shor

Agora, estime os recursos físicos para a RunProgram operação usando as suposições padrão. Adicione uma nova célula e copie e cole o seguinte código:

result = qsharp.estimate("RunProgram()")

result

A qsharp.estimate função cria um objeto de resultado que você pode usar para exibir uma tabela com as contagens gerais de recursos físicos. Você pode inspecionar os detalhes de custo recolhendo os grupos, que têm mais informações.

Por exemplo, feche o grupo de parâmetros de qubit lógico para ver se a distância do código é 21 e o número de qubits físicos é 882.

| Parâmetro qubit lógico | Value |

|---|---|

| Regime QEC | surface_code |

| Distância do código | 21 |

| Qubits físicos | 882 |

| Tempo de ciclo lógico | 8 milisegundos |

| Taxa de erro de qubit lógico | 3,00E-13 |

| Pré-fator de cruzamento | 0.03 |

| Limite de correção de erros | 0,01 |

| Fórmula de tempo de ciclo lógico | (4 * twoQubitGateTime + 2 * oneQubitMeasurementTime) * codeDistance |

| Fórmula de qubits físicos | 2 * codeDistance * codeDistance |

Gorjeta

Para uma versão mais compacta da tabela de saída, você pode usar result.summaryo .

Diagrama de espaços

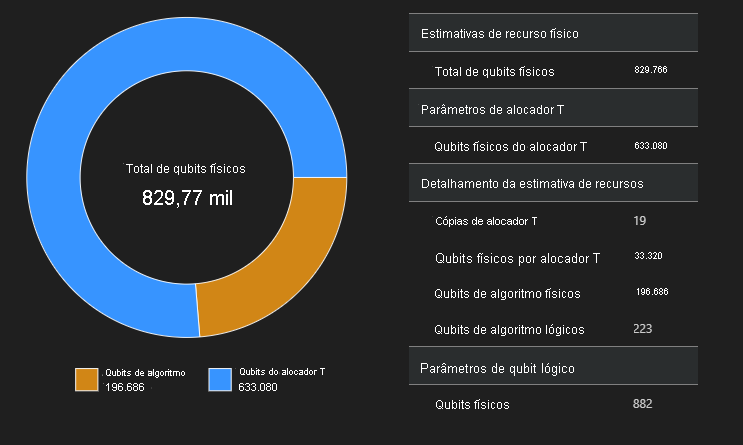

A distribuição de qubits físicos usados para o algoritmo e as fábricas T é um fator que pode afetar o design do seu algoritmo. Você pode usar o qsharp-widgets pacote para visualizar essa distribuição para entender melhor os requisitos de espaço estimados do algoritmo.

from qsharp_widgets import SpaceChart

SpaceChart(result)

Neste exemplo, o número de qubits físicos necessários para executar o algoritmo é 829766, 196686 dos quais são qubits de algoritmo e 633080 dos quais são qubits de fábrica T.

Compare as estimativas de recursos para diferentes tecnologias de qubit

O Azure Quantum Resource Estimator permite executar várias configurações de parâmetros de destino e comparar os resultados. Isso é útil quando você deseja comparar o custo de diferentes modelos de qubit, esquemas QEC ou orçamentos de erro.

Você também pode construir uma lista de parâmetros de estimativa usando o EstimatorParams objeto.

from qsharp.estimator import EstimatorParams, QubitParams, QECScheme, LogicalCounts

labels = ["Gate-based µs, 10⁻³", "Gate-based µs, 10⁻⁴", "Gate-based ns, 10⁻³", "Gate-based ns, 10⁻⁴", "Majorana ns, 10⁻⁴", "Majorana ns, 10⁻⁶"]

params = EstimatorParams(6)

params.error_budget = 0.333

params.items[0].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.GATE_US_E3

params.items[1].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.GATE_US_E4

params.items[2].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.GATE_NS_E3

params.items[3].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.GATE_NS_E4

params.items[4].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.MAJ_NS_E4

params.items[4].qec_scheme.name = QECScheme.FLOQUET_CODE

params.items[5].qubit_params.name = QubitParams.MAJ_NS_E6

params.items[5].qec_scheme.name = QECScheme.FLOQUET_CODE

qsharp.estimate("RunProgram()", params=params).summary_data_frame(labels=labels)

| Modelo Qubit | Qubits lógicos | Profundidade lógica | Estados T | Distância do código | Fábricas T | Fração de fábrica T | Qubits físicos | rQOPS | Tempo de execução físico |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μs baseados em portão, 10⁻³ | 223 3,64 milhões | 4.70 milh | 17 | 13 | 40.54 % | 216,77 Milhares | 21,86 K | 10 horas | |

| μs baseados em portão, 10⁻⁴ | 223 | 3.64 milh | 4.70 milh | 9 | 14 | 43.17 % | 63,57 Milhares | 41,30 K | 5 horas |

| Baseado em portão, 10⁻³ | 223 3,64 milhões | 4.70 milh | 17 | 16 | 69.08 % | 416,89 Milhares | 32.79 milh | 25 segundos | |

| NS baseado em portão, 10⁻⁴ | 223 3,64 milhões | 4.70 milh | 9 | 14 | 43.17 % | 63,57 Milhares | 61,94 milh | 13 segundos | |

| Majorana ns, 10⁻⁴ | 223 3,64 milhões | 4.70 milh | 9 | 19 | 82.75 % | 501,48 K | 82.59 milh | 10 segundos | |

| Majorana ns, 10⁻⁶ | 223 3,64 milhões | 4.70 milh | 5 | 13 | 31.47 % | 42,96 Milhares | 148.67 milh | 5 segundos |

Extrair estimativas de recursos de contagens de recursos lógicos

Se você já conhece algumas estimativas para uma operação, o Resource Estimator permite incorporar as estimativas conhecidas no custo geral do programa para reduzir o tempo de execução. Você pode usar a LogicalCounts classe para extrair as estimativas de recursos lógicos de valores de estimativa de recursos precalculados.

Selecione Código para adicionar uma nova célula e, em seguida, insira e execute o seguinte código:

logical_counts = LogicalCounts({

'numQubits': 12581,

'tCount': 12,

'rotationCount': 12,

'rotationDepth': 12,

'cczCount': 3731607428,

'measurementCount': 1078154040})

logical_counts.estimate(params).summary_data_frame(labels=labels)

| Modelo Qubit | Qubits lógicos | Profundidade lógica | Estados T | Distância do código | Fábricas T | Fração de fábrica T | Qubits físicos | Tempo de execução físico |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μs baseados em portão, 10⁻³ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 27 | 13 | 0,6% | 37.38 milh | 6 anos |

| μs baseados em portão, 10⁻⁴ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 13 | 14 | 0,8% | 8.68 milh | 3 anos |

| Baseado em portão, 10⁻³ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 27 | 15 | 1.3% | 37,65 milh | 2 dias |

| NS baseado em portão, 10⁻⁴ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 13 | 18 | 1.2% | 8.72 milhões | 18 horas |

| Majorana ns, 10⁻⁴ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 15 | 15 | 1.3% | 26.11 milh | 15 horas |

| Majorana ns, 10⁻⁶ | 25481 | 1,2e+10 | 1,5E+10 | 7 | 13 | 0,5% | 6,25 milh | 7 horas |

Conclusão

No pior cenário, um computador quântico usando qubits μs baseados em porta (qubits que têm tempos de operação no regime de nanossegundos, como qubits supercondutores) e um código QEC de superfície precisaria de seis anos e 37,38 milhões de qubits para fatorar um inteiro de 2.048 bits usando o algoritmo de Shor.

Se você usar uma tecnologia de qubit diferente — por exemplo, qubits de íon ns baseados em porta — e o mesmo código de superfície, o número de qubits não muda muito, mas o tempo de execução se torna dois dias na pior das hipóteses e 18 horas no caso otimista. Se você alterar a tecnologia de qubit e o código QEC — por exemplo, usando qubits baseados em Majorana — a fatoração de um inteiro de 2.048 bits usando o algoritmo de Shor pode ser feita em horas com uma matriz de 6,25 milhões de qubits no melhor cenário.

A partir do seu experimento, você pode concluir que usar qubits Majorana e um código QEC Floquet é a melhor escolha para executar o algoritmo de Shor e fatorar um inteiro de 2.048 bits.