AI-Based Virtual Tutors – The Future of Education?

This post is co-authored by Chun Ming Chin, Technical Program Manager, and Max Kaznady, Senior Data Scientist, of Microsoft, with Luyi Huang, Nicholas Kao and James Tayali, students at University of California at Berkeley.

This blog post is about the UC Berkeley Virtual Tutor project and the speech recognition technologies that were tested as part of that effort. We share best practices for machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques in selecting models and engineering training data for speech and image recognition. These speech recognition models, which are integrated with immersive games, are currently being tested at middle schools in California.

Context

The University of California, Berkeley has a new program founded by alum and philanthropist Coleman Fung called the Fung Fellowship. In this program, students develop technology solutions to address education challenges such as enabling underserved children to help themselves in their learning. The solution involves building a Virtual Tutor that listens to what children say and interacts with them when playing educational games. The games were developed by a technology company founded by Coleman named Blue Goji. This work is being done in collaboration with the Partnership for a Healthier America, a nonprofit organization chaired by Michelle Obama.

[embed]https://youtu.be/4gag8mrLyUM[/embed]

GoWings Safari, a safari-themed educational game, enabled with a Virtual Tutor that interacts with the user.

One of the students working on the project is a first-generation UC Berkeley graduate from Malawi named James Tayali. James said: "This safari game is important for kids who grow up in environments that expose them to childhood trauma and other negative experiences. Such kids struggle to pay attention and excel academically. Combining the educational experience with interactive, immersive games can improve their learning focus."

As an orphan from Malawi who struggled to focus in school, this is an area that James can relate to. James had to juggle family issues and work on part-time jobs to support himself. Despite humble beginnings, James worked hard and attended UC Berkeley with scholarship support from the MasterCard Foundation. He is now paying it forward to the next generation of children. "This project can help children who share similar stories as me by helping them to let go of their past traumatic experiences, focus on their present education and give them hope for their future," James added.

James Tayali (left), UC Berkeley Public Health major class of 2017 alum and Coleman

Fung (right), posing with the safari game shown on the monitor screen.

The fellowship program was taught by a Microsoft Search and Artificial Intelligence program manager, Chun Ming, who is also a UC Berkeley alum. He also advised the team that built the Virtual Tutor, which includes James Tayali, who majored in Public Health and served as team's product designer; Luyi Huang, an Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (EECS) student who led the programming tasks; and Nicholas Kao, an Applied Math and Data Science student, who drove the data collection and analysis. Much of this work was done remotely across three locations – Redmond, WA, Berkeley, CA, and Austin, TX.

UC Berkeley Fung Fellowship students Luyi Huang (left) and Nicholas Kao (right).

Chun Ming teaching speech recognition and artificial intelligence lectures to UC Berkeley students.

Insights from the Virtual Tutor Project

This article shares technical insights from the team in a couple of areas:

- Model selection strategy and engineering considerations for eventual real-world deployment, so others who are doing something similar have more confidence investing in a model upfront that fits their scenario right from the start.

- Training data engineering techniques that are useful references not only for speech recognition, but also for other scenarios such as image recognition.

Model Selection – Selecting the Speech Recognition Model

We explored speech recognition technologies from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Google, Amazon, and Microsoft, and eventually zoomed into the following options:

1. Bing Speech Recognition Service

Microsoft Bing's paid speech recognition service showed an accuracy of 100% although there was a 4-second wait to get results back from Bing's remote servers. While the accuracy is impressive, we did not have the flexibility to adapt this black box model to other speech accents and background noise. One potential workaround is to process the output from the black box (i.e. post-processing).

2. CMU Open Source Statistical Model

We also explored other free, faster speech recognition models that are accessed locally rather than over a remote server. Eventually, we chose an open source statistical model, Sphinx, which had an initial accuracy of 85% and improved the latency from Bing Speech API's 4 seconds down to 3 seconds. Unlike Bing's black box solution, we can look inside the model to improve accuracy. For instance, we can reduce the search space of words needed for lookup in the dictionary or adapt the model with more speech training data. Sphinx has a 30-year-old legacy, originally developed by CMU researchers who are coincidentally now at Microsoft Research (MSR) – they include Xuedong Huang, Microsoft Technical Fellow, Fil Alleva, Partner Research Manager, and Hsiao-Wuen Hon, Corporate Vice President for MSR Asia.

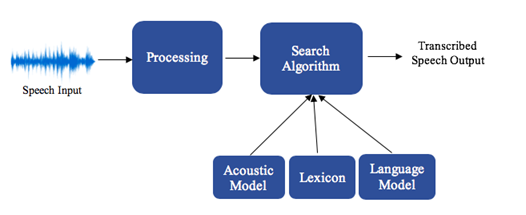

Pre-defined, human features and linguistic structure in CMU's open source speech recognition model.

3. Azure Deep Learning Model

The students were also connected to the Boston-based Microsoft Azure team at the New England Research & Development (NERD) center. With access to NERD's work on an Azure AI product known as the Data Science Virtual Machine notebook, the Fellowship students achieved a Virtual Tutor speech recognition accuracy of 91.9%. Moreover, the average model execution time is the same at 0.5 seconds per input speech file between NERD's and CMU's model. An additional prototype deep learning model was developed by NERD based on a winning solution of the Detection and Classification of Acoustic Scenes and Events (DCASE) 2017 challenge. This model can push classification accuracy up even further and scales to larger training datasets.

Machine learned features with Azure's deep learning model.

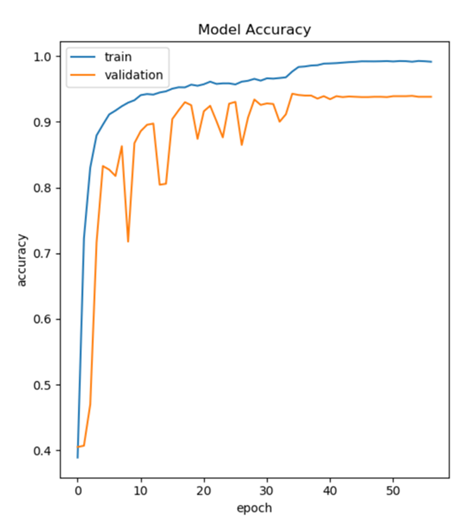

Plot of NERD's model accuracy on the y-axis against the number of passes through the full

training data (i.e. epochs) on the x-axis. The final accuracy evaluated on a measurement set is 91.9%.

Training Data Engineering

The lack of audio training data was a hurdle in maximizing the potential of the deep learning model. More training data can always improve CMU's speech recognition model.

1. Solve Training and Testing Data Mismatch Problems

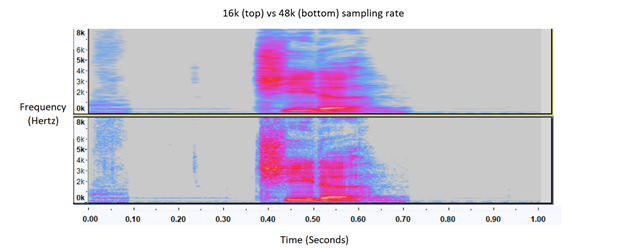

We downloaded synthetic speaker audio files from the public web and collected audio files from UC Berkeley volunteers at sampling rate of 16kHz. Initially, we observed that more training data did not increase test accuracy on Oculus microphone. This problem was due to sampling rate mismatch between the training data (16kHz) and the Oculus microphone input (48kHz). Once the input was down sampled, the improved Sphinx mode had better accuracy.

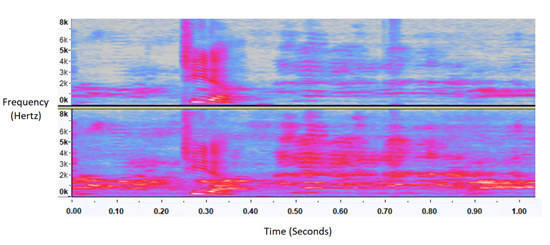

Visual representation of the spectrum of the frequencies of sound varying with time (i.e. Spectrogram) comparison between 16kHz sampling (top) and 48kHz (bottom). Note bottom 48kHz sampled spectrogram has finer resolution.

2. Synthetic Speaker Audio

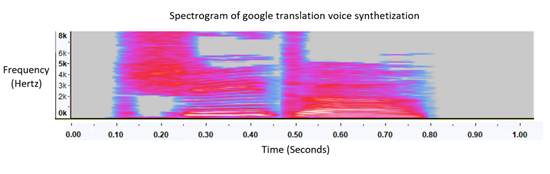

Data biases due to speaker's gender and accents must be balanced out by increasing the quality and quantity of training data. To address this, we imported synthesized male/female audio samples from translators such as Bing. We could train our model using these new synthesized audio samples in conjunction with our current data. However, we found that synthesized audio lacked the naturally occurring zig zag feature variations in human voice. It was "too clean" to represent natural human voice accurately in live setting.

Spectrogram comparison between synthesized voice (top) and human speaker voice (bottom)

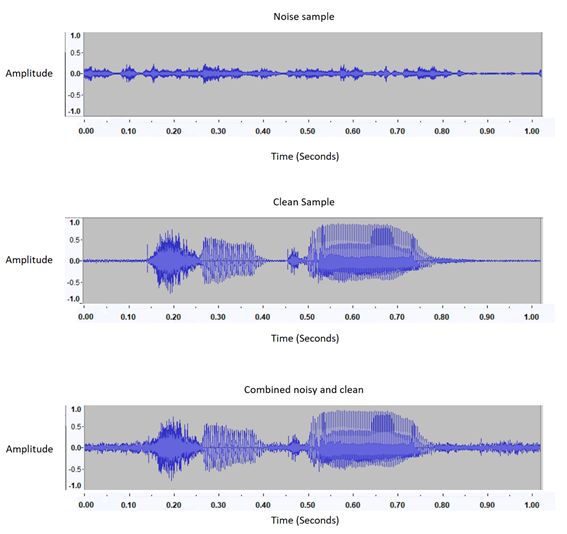

3. Background Noise and Speaker Signal Combination

Another problem is there are varying loud background noises that the Oculus microphone is unable to denoise automatically. This interferes with the model's ability to differentiate background noise from the speaker's signal. To solve this, we combined an audio sample with multiple background noises.

The y axis "Amplitude" is the normalized dB scale (where -1 is no signal

and +1 is the strongest signal) representing the loudness in the audio.

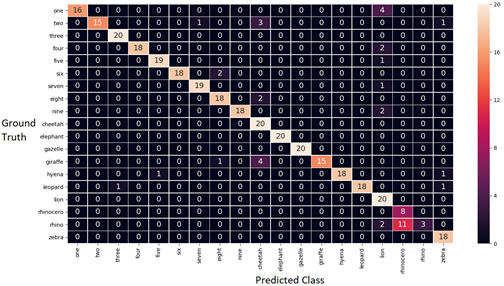

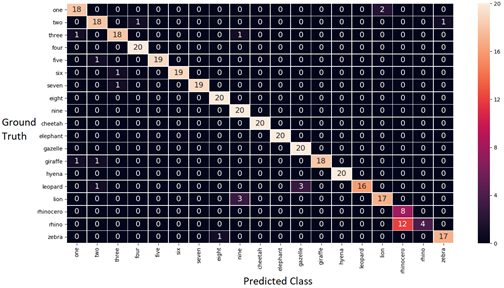

This provided a large amount of audio samples and allowed us to customize the model towards the Virtual Tutor's live environment. With the additional synthesized samples, we trained a more accurate model as shown in the Confusion Matrix below. This matrix shows test examples where the model is confused due to mismatch between the predicted class column and ground truth row. Correct predictions are shown along the diagonal line of the matrix. The confusion matrix is a good way to visualize what classes require targeted training data improvements.

Confusion matrix before combining background noise and speaker signal as new training data for CMU's Sphinx model. Model accuracy is 93%.

Confusion matrix after combining background noise and speaker signal as new training data for CMU's Sphinx model. Model accuracy is 96%.

The synthesized noise had some problems. We discovered a few outliers when we overlaid (on time scale) the clean signal and synthesized noise without any signal adjustments. These outliers occurred because the noise was more prominent than the speaker's signal.

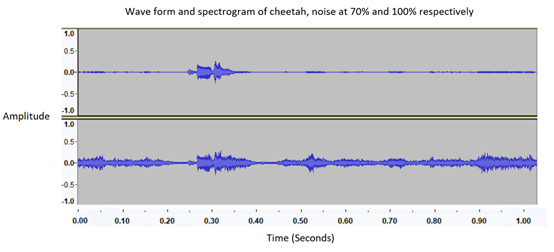

4. Signal-to-Noise Ratio Optimization

To compensate for the above issue, we adjusted the relative decibel (dB) level ratios between the two overlaid audio files. Using Root Mean Square (RMS) to estimate the dB levels of each audio file, we were able suppress the noisy audio allowing the speakers voice to take precedence when training and predicting. Through a series of testing we determined that the average dB level of noise is about 70% of the average of our clean audio dB level. This allows us to keep up a 95% accuracy when tested on a redundant training and testing set. Anything higher than 80% decreases accuracy at an increasing rate.

Waveform plot showing noise at 70% (top) and 100% (bottom). The y axis "Amplitude" is the normalized

dB scale (where -1 is no signal and +1 is the strongest signal) representing the loudness in the audio.

Spectrogram plot showing noise at 70% (top) and 100% (bottom).

Note the bottom noise at 100% has more blue and pink regions.

Summary

The story of the UC Berkeley Virtual Tutor project began in the Fall of 2016. We first tested a variety of speech recognition technologies and then explored a range of training data engineering techniques. Currently, our speech recognition models have been integrated with the game and are being tested at middle schools in California.

For those of you looking to add speech recognition capabilities to your projects, you should consider the following options based on our findings:

- For ease of integration and high accuracy, try the Bing Speech API. It lets you use 5000 free transactions per month.

- For faster end to end response times and model customizability to improve accuracy for specific environments, try CMU's statistical model Sphinx.

- For scenarios where you have access to a lot of training data (e.g. over 100,000 rows of training examples), Azure's deep learning model can be a better option, for both speed and accuracy.

Chun Ming, Max, Luyi, Nick & James