The CFF 2 Charstring Format (OpenType 1.8)

1 Introduction

The CFF 2 CharString format provides a method for compact encoding of glyph procedures in an outline font program. CFF 2 charstrings are intended for use only with a CFF 2 font table in an OpenType font file.

The CFF 2 CharString format is closely descended from the Type 2 CharString format. Type 2 CharStrings are documented in Adobe Technical Note #5177, “The Type 2 Charstring Format #5177”, which is available at Adobe Font Technical Notes.

The motivation for developing the CFF 2 CharString format was twofold:

- Reduce the size of CFF fonts by removing all the data which is duplicated eslewhere in the OpenType font, or is not used in the context of OpenType font files.

- Add support for OpenType Font Variations. (See the chapter, OpenType Font Variations Overview for a general overview of OpenType Font Variations and a complete list of the tables required to support a variable font.)

Accordingly, the CFF 2 CharString format has added some new operators, and has removed many more operators. However, the encoding of operators and operands is the same between Type 2 and CFF 2 CharStrings; interpreters will need relatively little change to process both formats. See Appendix D Changes From Type 2 CharStrings for a complete list of the differences between Type 2 and CFF 2 CharString formats.

This document only describes how CFF 2 charstrings are encoded, and does not attempt to explain the reasons for choosing various options. CFF 2 charstrings are based on Type 1 font concepts, and this document assumes familiarity with the Type 1 font format specification. For more information, please see “Adobe Type 1 Font Format” at Adobe Font Technical Notes. Also, familiarity with the CFF 2 font format is assumed; please see the Compact Font Format Version 2 ('CFF 2') chapter for details.

2 CFF 2 Charstrings

The following sections describe the general concepts of encoding a CFF 2 charstring.

2.1 Hints

The CFF 2 charstring format supports six hint operators: hstem, vstem, hstemhm, vstemhm, hintmask, and cntrmask. The hint information must be declared at the beginning of a charstring (see section 3.1) using the hstem, vstem, hstemhm, and vstemhm operators, each of which may each take arguments for multiple stem hints.

CFF 2 hint operators aid the rasterizer in recognizing and controlling stems and counter areas within a glyph. A stem generally consists of two positions (edges) and the associated width. Edge stem hints help to control character features where there is only a single edge (see section 4.3). The CFF 2 charstring format includes edge hints, which are equivalent to the Type 1 concept of ghost hints (see section on ghost hints, page 57, of “Adobe Type 1 Font Format”). They are used to locate an edge rather than a stem that has two edges. A stem width value of -20 is reserved for a top or right edge, and a value of -21 for a bottom or left edge. The operation of hints with other negative width values is undefined.

hintmask

The hintmask operator has the same function as that described in “Changing Hints within a Character,” section 8.1, page 69, of “Adobe Type 1 Font Format.” It provides a means for activating or deactivating stem hints so that only a set of non-overlapping hints are active at one time. The hintmask operator is followed by one or more data bytes that specify the stem hints which are to be active for the subsequent path construction. The number of data bytes must be exactly the number needed to represent the number of stems in the original stem list (those stems specified by the hstem, vstem, hstemhm, and vstemhm commands), using one bit in the data bytes for each stem in the original stem list. Bits with a value of one indicate stems that are active, and a value of zero indicates stems that are inactive.

cntrmask

The cntrmask (countermask) hint causes arbitrary but nonoverlapping collections of counter spaces in a character to be controlled in a manner similar to how stem widths are controlled by the stem hint commands (see Adobe Technical Note #5015, “The Type 1 Font Format Supplement” for more information). The cntrmask operator is followed by one or more data bytes that specify the index number of the stem hints on both sides of a counter space. The number of data bytes must be exactly the number needed to represent the number of stems in the original stem list (those stems specified by the hstem, vstem, hstemhm, or vstemhm commands), using one bit in the data bytes for each stem in the original stem list.

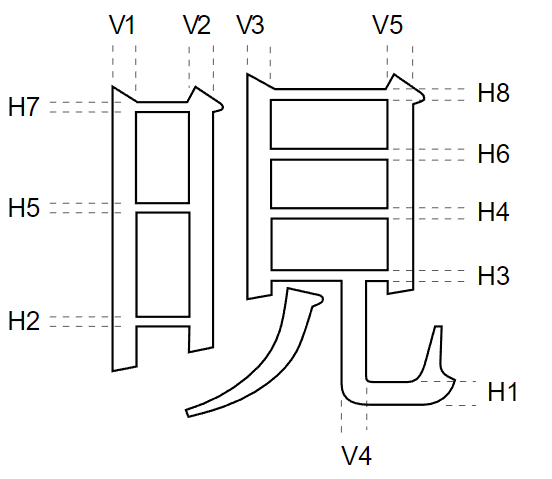

For the example shown in Figure 1, the stem list for the glyph would be:

H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 H7 H8 V1 V2 V3 V4 V5

and the following cntrmask commands would be used to control the counter spaces between those stems:

cntrmask 0xB5 0xE8 (H1 H3 H4 H6 H8 V1 V2 V3 V5)cntrmask 0x4A 0x00(H2 H5 H7)

The bits set in the data bytes indicate that the corresponding stem hints delimit the desired set of counters. Hints specified in the first command have a higher priority than those in the second command. Notice that the V4 stem does not delimit an appropriate counter space, and hence is not referenced in this example.

Note that hints are just that, hints, or recommendations. They are additional guidelines to an intelligent rasterizer.

If the font’s LanguageGroup is not equal to 1 (a LanguageGroup value of 1 indicates complex Asian language glyphs), the cntrmask operator, with three stems, can be used in place of the hstem3 and vstem3 hints in the Type 1 format, as long as the related conditions specified in the Type 1 specification are met. For more information on Counter Control hints, see Adobe Technical Note #5015, “Type 1 Font Format Supplement.”

2.2 The Flex Mechanism

The flex mechanism is provided to improve the rendering of shallow curves, representing them as line segments at small sizes rather than as small humps or dents in the character shape. It is essentially a path construction mechanism: the arguments describe the construction of two curves, with an additional argument that is used as a hint for when the curves should be rendered as a straight line at smaller sizes and resolutions.

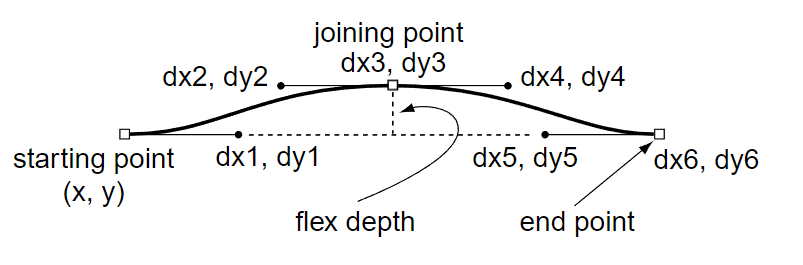

The CFF 2 flex mechanism is general; there are no restrictions on what type or orientation of curve may be expressed with a flex operator. The flex operator is used for the general case; special cases can use the flex1, hflex, or hflex1 operators for a more efficient encoding. Figure 2 shows an example of the flex mechanism used for a horizontal curve, and Figure 3 shows an example of flex curves at non-standard angles.

The flex operators can be used for any curved character feature, in any orientation or depth, that meets the following requirements:

- The character feature must be capable of being represented as exactly two curves, drawn by two rrcurveto operators.

- The curves must meet at a common point called the joining point.

- The length of the combined curve must exceed its depth.

2.3 Subroutines

A CFF 2 font program can use subroutines to reduce the storage requirements by combining the program statements that describe common elements of the characters in the font.

Subroutines may be local, or global. Local subroutines are only accessible from the charstring programs in the current font. Global subroutines are those that are shared amongst the various fonts in a FontSet (see Adobe Technical Note #5176, “The CFF Font Format Specification” for more information).

Subroutines may contain sections of charstrings, and are encoded the same as CFF 2 charstrings. They are called with the callsubr (for a local subroutine) or callgsubr (for a global subroutine) operator, using a biased index into the local or global Subrs array as the argument.

Note 1. Unlike the biasing in the Type 1 format, in CFF 2 the bias is not optional, and is fixed — based on the number of subroutines.

Charstring subroutines may call other subroutines, to the depth allowed by the implementation limits (see Appendix B). A charstring subroutine must end with either an endchar or a return operator. If the subroutine ends with an endchar operator, the return is not necessary.

3 Charstring Encoding

A CFF 2 charstring program is a sequence of unsigned 8-bit bytes that encode numbers and operators. The byte value specifies a operator, a number, or subsequent bytes that are to be interpreted in a specific manner.

The bytes are decoded into numbers and operators. One reason the format is more economical than Type 1 is because the CFF 2 charstring interpreter is required to count the number of arguments on the argument stack. It can thus detect additional sets of arguments for a single operator. The stack depth implementation limit is specified in Appendix B.

A number, decoded from a charstring, is pushed onto the CFF 2 argument stack. An operator expects its arguments in order from this argument stack with all arguments generally taken from the bottom of the stack (first argument bottom-most); however, some operators, particularly the subroutine operators, normally work from the top of the stack. If an operator returns results, they are pushed onto the CFF 2 argument stack (last result topmost).

In the following discussion, all numeric constants are decimal numbers, except where indicated.

3.1 CFF 2 Charstring Organization

The sequence and form of a CFF 2 charstring program may be represented as:

-

{hs* vs* cm* hm* mt subpath}? {mt subpath}*

Where:

- hs = hstem or hstemhm command

- vs = vstem or vstemhm command

- cm = cntrmask operator

- hm = hintmask operator

- mt = moveto (i.e. any of the moveto) operators

- subpath = refers to the construction of a subpath (one complete closed contour), which may include hintmask operators where appropriate.

and the following symbols indicate specific usage:

- * zero or more occurrences are allowed

- ? zero or one occurrences are allowed

- + one or more occurrences are allowed

- { } indicates grouping

Stated in words, the constraints on the sequence of operators in a charstring are as follows:

CFF 2 charstrings must be structured with operators, or classes of operators, sequenced in the following specific order:

- Hints: zero or more of each of the following hint operators, in exactly the following order: hstem, hstemhm, vstem, vstemhm, cntrmask, hintmask. Each entry is optional, and each may be expressed by one or more occurrences of the operator. The hint operators cntrmask and/or hintmask must not occur if the charstring has no stem hints.

- Path Construction: The first path of a charstring that contains no hints must begin with one of the moveto operators so that the preceding width can be detected properly.

- Zero or more path construction operators are used to draw the path of the character; the second and all subsequent subpaths must also begin with one of the moveto operators. The hintmask operator may be used as needed.

Note 2. Charstrings may contain subr and gsubr calls as desired at any point between complete tokens (operators or numbers). This means that a subr (gsubr) call must not occur between the bytes of a multibyte commands (for example, hintmask).

3.2 Charstring Number Encoding

A charstring byte containing the values from 32 through 254 inclusive indicates an integer. These values are decoded in three ranges (also see Table 1):

- A charstring byte containing a value, v, between 32 and 246 inclusive, specifies the integer v − 139. Thus, the integer values from −107 through 107 inclusive may be encoded in a single byte.

- A charstring byte containing a value, v, between 247 and 250 inclusive, indicates an integer involving the next byte, w, according to the formula:

-

(v − 247) * 256 + w + 108

-

- Thus, the integer values between 108 and 1131 inclusive can be encoded in 2 bytes in this manner.

-

A charstring byte containing a value, v, between 251 and 254 inclusive, indicates an integer involving the next byte, w, according to the formula:

-

− [(v − 251) * 256] − w − 108

-

- Thus, the integer values between −1131 and −108 inclusive can be encoded in 2 bytes in this manner.

If the charstring byte contains the value 255, the next four bytes indicate a two’s complement signed number. The first of these four bytes contains the highest order bits, the second byte contains the next higher order bits and the fourth byte contains the lowest order bits. This number is interpreted as a Fixed; that is, a signed number with 16 bits of fraction.

Note 3. The CFF 2 interpretation of a number encoded in five-bytes (those with an initial byte value of 255) differs from how it is interpreted in the Type 1 format.

In addition to the 32 to 255 range of values, a ShortInt value is specified by using the operator (28) followed by two bytes which represent numbers between -32768 and +32767. The most significant byte follows the (28). This allows a more compact representation of large numbers which occur occasionally in fonts, but perhaps more importantly, this will allow more compact encoding of numbers which may be used as arguments to callsubr and callgsubr.

| Charstring Byte Value | Interpretation | Number Range Represented | Bytes Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – 11 | operators | operators 0 to 11 | 1 |

| 12 | escape: next byte interpreted as additional operators | additional 0 to 255 range for operator codes | 2 |

| 13 – 18 | operators | operators 13 to 18 | 1 |

| 19, 20 | operators (hintmask and cntrmask) | operators 19, 20 | 2 or more |

| 21 – 27 | operators | operators 21 to 27 | 1 |

| 28 | following 2 bytes interpreted as a 16-bit two’s complement number | -32768 to +32767 | 3 |

| 29 – 31 | operators | operators 29 to 31 | 1 |

| 32 – 246 | result = v-139 | -107 to +107 | 1 |

| 247 – 250 | with next byte, w, result = (v-247)*256+w+108 | +108 to +1131 | 2 |

| 247 – 250 | with next byte, w, result = -[(v-251)*256]-w -108 | -108 to -113 | 2 |

| 255 | 255 next 4 bytes interpreted as a 32-bit two’s-complement number | 16-bit signed integer with 16 bits of fraction | 5 |

3.3 CharString Operator Encoding

Charstring operators are encoded in one or two bytes.

Single byte operators are encoded in one byte that contains a value between 0 and 31 inclusive, excluding 12 and 28. Not all possible operator encoding values are defined (see Appendix A for a list of operator encoding values). The behavior of undefined operators is unspecified.

If an operator byte contains the value 12, then the value in the next byte specifies an operator. This escape mechanism allows many extra operators to be encoded.

4 Charstring Operators

CFF 2 charstring operators are divided into five groups, classified by function: 1) path construction; 2) finishing a path; 3) hints; 4) subroutine; and 5) variation data support.

The following definitions use a format similar to that used in the PostScript Language Reference Manual. Parentheses following the operator name either include the operator value that represents this operator in a charstring byte, or the two values (beginning with 12) that represent a two-byte operator.

Many operators take their arguments from the bottom-most entries in the CFF 2 argument stack; this behavior is indicated by the stack bottom symbol ‘|-’ appearing to the left of the first argument. Operators that clear the argument stack are indicated by the stack bottom symbol ‘|-’ in the result position of the operator definition.

Because of this stack-clearing behavior, in general, arguments are not accumulated on the CFF 2 argument stack for later removal by a sequence of operators, arguments generally may be supplied only for the next operator. Notable exceptions occur with subroutine calls and with arithmetic and conditional operators. All stack operations must observe the stack limit (see Appendix B).

4.1 Path Construction Operators

In a CFF 2 charstring, a path is constructed by sequential application of one or more path construction operators. The current point is initially the (0, 0) point of the character coordinate system. The operators listed in this section cause the current point to change, either by a moveto operation, or by appending one or more curve or line segments to the current point. Upon completion of the operation, the current point is updated to the position to which the move was made, or to the last point on the segment or segments.

Many of the operators can take multiple sets of arguments, which indicate a series of path construction operations. The number of operations are limited only by the limit on the stack size (see Appendix B).

All Bézier curve path segments are drawn using six arguments, dxa, dya, dxb, dyb, dxc, dyc; where dxa and dya are relative to the current point, and all subsequent arguments are relative to the previous point. A number of the curve operators take advantage of the situation where some tangent points are horizontal or vertical (and hence the value is zero), thus reducing the number of arguments needed.

The flex operators are considered path construction commands because they specify the drawing of two curves. There is also an additional argument that serves as a hint as to when to render the curves as a straight line at small sizes and low resolutions.

The following are three types of moveto operators. For the initial moveto operators in a charstring, the arguments are relative to the (0, 0) point in the character’s coordinate system; subsequent moveto operators’ arguments are relative to the current point.

Every character path and subpath must begin with one of the moveto operators. If the current path is open when a moveto operator is encountered, the path is closed before performing the moveto operation.

- rmoveto |- dx1 dy1 rmoveto (21) |-

- moves the current point to a position at the relative coordinates (dx1, dy1).

- hmoveto |- dx1 hmoveto (22) |-

- moves the current point dx1 units in the horizontal direction.

- vmoveto |- dy1 vmoveto (4) |-

- moves the current point dy1 units in the vertical direction. See

- rlineto |- {dxa dya}+ rlineto (5) |-

- appends a line from the current point to a position at the relative coordinates dxa, dya. Additional rlineto operations are performed for all subsequent argument pairs. The number of lines is determined from the number of arguments on the stack.

- hlineto |- dx1 {dya dxb}* hlineto (6) |-

- |- {dxa dyb}+ hlineto (6) |-

- appends a horizontal line of length dx1 to the current point. With an odd number of arguments, subsequent argument pairs are interpreted as alternating values of dy and dx, for which additional lineto operators draw alternating vertical and horizontal lines. With an even number of arguments, the arguments are interpreted as alternating horizontal and vertical lines. The number of lines is determined from the number of arguments on the stack.

- vlineto |- dy1 {dxa dyb}* vlineto (7) |-

- |- {dya dxb}+ vlineto (7) |-

- appends a vertical line of length dy1 to the current point. With an odd number of arguments, subsequent argument pairs are interpreted as alternating values of dx and dy, for which additional lineto operators draw alternating horizontal and vertical lines. With an even number of arguments, the arguments are interpreted as alternating vertical and horizontal lines. The number of lines is determined from the number of arguments on the stack.

- rrcurveto |- {dxa dya dxb dyb dxc dyc}+ rrcurveto (8) |-

- appends a Bézier curve, defined by dxa...dyc, to the current point. For each subsequent set of six arguments, an additional curve is appended to the current point. The number of curve segments is determined from the number of arguments on the number stack and is limited only by the size of the number stack.

- hhcurveto |- dy1? {dxa dxb dyb dxc}+ hhcurveto (27) |-

- appends one or more Bézier curves, as described by the dxa...dxc set of arguments, to the current point. For each curve, if there are 4 arguments, the curve starts and ends horizontal. The first curve need not start horizontal (the odd argument case). Note the argument order for the odd argument case.

- hvcurveto |- dx1 dx2 dy2 dy3 {dya dxb dyb dxc dxd dxe dye dyf}* dxf? hvcurveto (31) |-

- |- {dxa dxb dyb dyc dyd dxe dye dxf}+ dyf? hvcurveto (31) |-

- appends one or more Bézier curves to the current point. The tangent for the first Bézier must be horizontal, and the second

must be vertical (except as noted below).

If there is a multiple of four arguments, the curve starts horizontal and ends vertical. Note that the curves alternate between start horizontal, end vertical, and start vertical, and end horizontal. The last curve (the odd argument case) need not end horizontal/vertical. - rcurveline |- {dxa dya dxb dyb dxc dyc}+ dxd dyd rcurveline (24) |-

- is equivalent to one rrcurveto for each set of six arguments dxa...dyc, followed by exactly one rlineto using the dxd, dyd arguments. The number of curves is determined from the count on the argument stack.

- rlinecurve |- {dxa dya}+ dxb dyb dxc dyc dxd dyd rlinecurve (25) |-

- is equivalent to one rlineto for each pair of arguments beyond the six arguments dxb...dyd needed for the one rrcurveto command. The number of lines is determined from the count of items on the argument stack.

- vhcurveto |- dy1 dx2 dy2 dx3 {dxa dxb dyb dyc dyd dxe dye dxf}* dyf? vhcurveto (30) |-

- |- {dya dxb dyb dxc dxd dxe dye dyf}+ dxf? vhcurveto (30) |-

- appends one or more Bézier curves to the current point, where the first tangent is vertical and the second tangent is horizontal. This command is the complement of hvcurveto; see the description of hvcurveto for more information.

- vvcurveto |- dx1? {dya dxb dyb dyc}+ vvcurveto (26) |-

- appends one or more curves to the current point. If the argument count is a multiple of four, the curve starts and ends vertical. If the argument count is odd, the first curve does not begin with a vertical tangent.

- flex |- dx1 dy1 dx2 dy2 dx3 dy3 dx4 dy4 dx5 dy5 dx6 dy6 fd flex (12 35) |-

- causes two Bézier curves, as described by the arguments (as shown in Figure 2 below), to be rendered as a straight line when the flex depth is less than fd /100 device pixels, and as curved lines when the flex depth is greater than or equal to fd/100 device pixels. The flex depth for a horizontal curve, as shown in Figure 2, is the distance from the join point to the line connecting the start and end points on the curve. If the curve is not exactly horizontal or vertical, it must be determined whether the curve is more horizontal or vertical by the method described in the flex1 description, below, and as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2 Flex Hint Example Note 4. In cases where some of the points have the same x or y coordinate as other points in the curves, arguments may be omitted by using one of the following forms of the flex operator, hflex, hflex1, or flex1.

- hflex |- dx1 dx2 dy2 dx3 dx4 dx5 dx6 hflex (12 34) |-

- causes the two curves described by the arguments dx1...dx6 to be rendered as a straight line when the flex depth is less than 0.5 (that is, fd is 50) device pixels, and as curved lines when the flex depth is greater than or equal to 0.5 device pixels.

hflex is used when the following are all true:- a) the starting and ending points, first and last control points have the same y value.

- b) the joining point and the neighbor control points have the same y value.

- c) the flex depth is 50.

- hflex1 |- dx1 dy1 dx2 dy2 dx3 dx4 dx5 dy5 dx6 hflex1 (12 36) |-

- causes the two curves described by the arguments to be rendered as a straight line when the flex depth is less than 0.5 device pixels, and as curved lines when the flex depth is greater than or equal to 0.5 device pixels.

hflex1 is used if the conditions for hflex are not met but all of the following are true:- a) the starting and ending points have the same y value,

- b) the joining point and the neighbor control points have the same y value.

- c) the flex depth is 50.

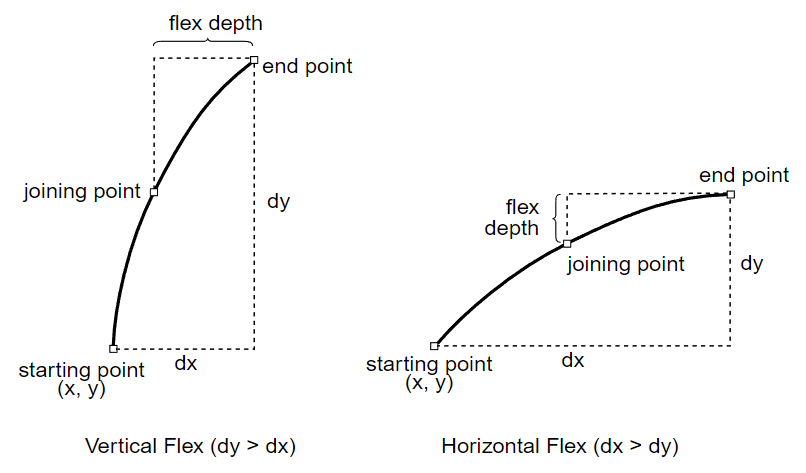

- flex1 |- dx1 dy1 dx2 dy2 dx3 dy3 dx4 dy4 dx5 dy5 d6 flex1 (12 37) |-

- causes the two curves described by the arguments to be rendered as a straight line when the flex depth is less than 0.5 device pixels, and as curved lines when the flex depth is greater than or equal to 0.5 device pixels.

The d6 argument will be either a dx or dy value, depending on the curve (see Figure 3). To determine the correct value, compute the distance from the starting point (x, y), the first point of the first curve, to the last flex control point (dx5, dy5) by summing all the arguments except d6; call this (dx, dy). If abs(dx) > abs(dy), then the last point’s x-value is given by d6, and its y-value is equal to y. Otherwise, the last point’s x-value is equal to x and its y-value is given by d6.

flex1 is used if the conditions for hflex and hflex1 are not met but all of the following are true:- a) the starting and ending points have the same x or y value,

- b) the flex depth is 50.

Figure 3 Flex Depth Calculations

4.2 Finishing a CharString Outline Definition

CFF 2 CharStrings differ from Type 2 CharStrings in that there is no operator for finishing a charstring outline definition.The end of the CharString data implies the end of the path, and serves the same purpose as the Type 2 endchar operator.

The smallest legal CharString is simply an empty byte string.

4.3 Hint Operators

All hints must be declared at the beginning of the charstring program, after the width (see section 3.1 for details).

- hstem |- y dy {dya dyb}* hstem (1) |-

- specifies one or more horizontal stem hints (see the following section for more information about horizontal stem hints). This allows multiple pairs of numbers, limited by the stack depth, to be used as arguments to a single hstem operator.

It is required that the stems are encoded in ascending order (defined by increasing bottom edge). The encoded values are all relative; in the first pair, y is relative to 0, and dy specifies the distance from y. The first value of each subsequent pair is relative to the last edge defined by the previous pair.

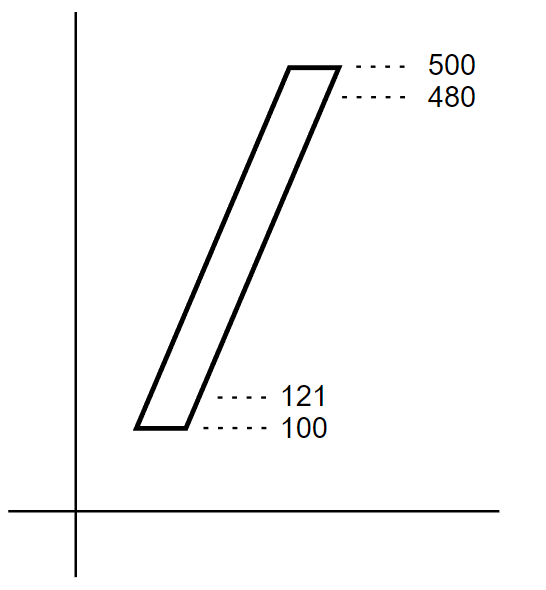

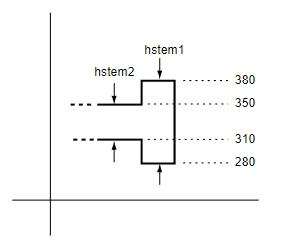

A width of -20 specifies the top edge of an edge hint, and -21 specifies the bottom edge of an edge hint. All other negative widths have undefined meaning.Figure 4 shows an example of the encoding of a character stem that uses top and bottom edge hints. The edge stem hint serves to control the position of the edge of the stem in situations where controlling the stem width is not the primary purpose.

Figure 4 Encoding of Edge Hints The encoding for the edge stem hints shown in Figure 4 would be:

- 121 -21 400 -20 hstem

Figure 5 shows an example of overlapping hints on a sample feature of a character outline. The overlapping hints must be resolved by using two hintmask operators so that they are not both active at the same time.

Horizontal stem hints must not overlap each other. If there is any overlap, the hintmask operator must be used immediately after the hint declarations to establish the desired non-overlapping set of hints. hintmask may be used again later in the path to activate a different set of non-overlapping hints.

Figure 5 Encoding of Overlapping Hints The encoding for the example shown in Figure 5 would be:

- 280 100 -70 40 hstem

- vstem |- x dx {dxa dxb}* vstem (3) |-

- specifies one or more vertical stem hints between the x coordinates x and x+dx, where x is relative to the origin of the coordinate axes.

It is required that the stems are encoded in ascending order (defined by increasing left edge). The encoded values are all relative; in the first pair, x is relative to 0, and dx specifies the distance from x. The first value of each subsequent pair is relative to the last edge defined by the previous pair.

A width of -20 specifies the right edge of an edge hint, and -21 specifies the left edge of an edge hint. All other negative widths have undefined meaning.

Vertical stem hints must not overlap each other. If there is any overlap, the hintmask operator must be used immediately after the hint declarations to establish the desired non-overlapping set of hints. hintmask may be used again later in the path to activate a different set of non-overlapping hints. - hstemhm |- y dy {dya dyb}* hstemhm (18) |-

- has the same meaning as hstem (1), except that it must be used in place of hstem if the charstring contains one or more hintmask operators.

- vstemhm |- x dx {dxa dxb}* vstemhm (23) |-

- has the same meaning as vstem (3), except that it must be used in place of vstem if the charstring contains one or more hintmask operators.

- hintmask |- hintmask (19 + mask) |-

- specifies which hints are active and which are not active. If any hints overlap, hintmask must be used to establish a non-overlapping subset of hints. hintmask may occur any number of times in a charstring. Path operators occurring after a hintmask are influenced by the new hint set, but the current point is not moved. If stem hint zones overlap and are not properly managed by use of the hintmask operator, the results are undefined.

The mask data bytes are defined as follows:- The number of data bytes is exactly the number needed, one bit per hint, to reference the number of stem hints declared at the beginning of the charstring program.

- Each bit of the mask, starting with the most-significant bit of the first byte, represents the corresponding hint zone in the order in which the hints were declared at the beginning of the charstring.

- For each bit in the mask, a value of ‘1’ specifies that the corresponding hint shall be active. A bit value of ‘0’ specifies that the hint shall be inactive.

- Unused bits in the mask, if any, must be zero.

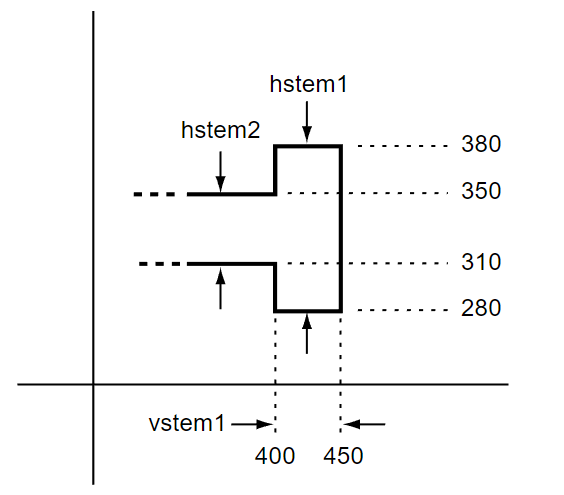

If hstem and vstem hints are both declared at the beginning of a charstring, and this sequence is followed directly by the hintmask or cntrmask operators, the vstem hint operator need not be included. For example, Figure 6 shows part of a character with hstem and vstem hints:

Figure 6 Hint Encoding Example If the first hint group is to be the hstem from 280 to 380 and the vstem from 400 to 450 (and only these three hints are defined), then the hints would be specified as:

- 280 100 -70 40 hstemhm 400 50 hintmask 0xa0

where the hex data 0xa0 (10100000) indicates which hints are active at the beginning of the path construction.

Note that the hstemhm is used to indicate that hint substitution is used. - cntrmask |- cntrmask (20 + mask) |-

- specifies the counter spaces to be controlled, and their relative priority. The mask bits in the bytes, following the operator, reference the stem hint declarations; the most significant bit of the first byte refers to the first stem hint declared, through to the last hint declaration. The counters to be controlled are those that are delimited by the referenced stem hints. Bits set to 1 in the first cntrmask command have top priority; subsequent cntrmask commands specify lower priority counters (see Figure 1 and the accompanying example).

4.4 Subroutine Operators

The numbering of subroutines is encoded more compactly by using the negative half of the number space, which effectively doubles the number of compactly encodable subroutine numbers. The bias applied depends on the number of subrs (gsubrs). If the number of subrs (gsubrs) is less than 1240, the bias is 107. Otherwise if it is less than 33900, it is 1131; otherwise it is 32768. This bias is added to the encoded subr (gsubr) number to find the appropriate entry in the subr (gsubr) array. Global subroutines may be used in a FontSet even if it only contains one font.

- callsubr subr# callsubr (10) —

- calls a charstring subroutine with index subr# (actually the subr number plus the subroutine bias number, as described in section 2.3) in the Subrs array. Each element of the Subrs array is a charstring encoded like any other charstring. Arguments pushed on the CFF 2 argument stack prior to calling the subroutine, and results pushed on this stack by the subroutine, act according to the manner in which the subroutine is coded. Calling an undefined subr (gsubr) has undefined results.

These subroutines are generally used to encode sequences of path operators that are repeated throughout the font program, for example, serif outline sequences. Subroutine calls may be nested to the depth specified in the implementation limits in Appendix B. - callgsubr globalsubr# callgsubr (29) —

- operates in the same manner as callsubr except that it calls a global subroutine.

4.5 Variation Data Operators

In order to support variation data in CFF 2 CharStrings, two new operators are added in CFF 2 CharStrings: vsindex and blend.

A variable font holds data representing the equivalent of several distinct design variations, and uses algorithms for interpolation — or blending — between these designs to derive a continuous range of design instances. This allows an entire family of fonts to be represented by a single variable font. For example, a variable font may contain data equivalent to Light and Heavy designs from a family, which can then be interpolated to derive instances for any weight in between Light and Heavy. Moreover, the single variable font provides even greater functionality since it supports a continuous range of variation between those source designs.

See the chapter, OpenType Font Variations Overview for general background on OpenType Font Variations, details on the tables used to support a variable font, terminology, and a specification of the interpolation algorithm used to blend values to derive specific design instances.

Outline data for a variable font in the CFF 2 format is built much like a non-variable CFF2 table would be built, with exactly the same structure and operators as would be used for the default design representation. However, wherever a value occurs in the default design, the single value for the one design is replaced with a set of delta values, followed by the blend operator. (For efficiency, the blend operator is actually called only at the end of a series of such delta sets, rather than after each one.)

Within a variable font, different glyphs can use different sets of regions and associated delta values for the blending operation. When processing a given glyph, the interpreter must determine which set to use. These sets are stored in the CFF 2 table in an ItemVariationStore structure. The ItemVariationStore contains one or more ItemVariationData subtables, each of which contains a list of Variation Regions. The first ItemVariationData subtable defines the default subtable to use, when no other has been specified. When a ItemVariationData subtable other than the default is needed for a set of delta values, the vsindex operator is used. When this operator is used in a Private DICT to set a non-default itemVariationData index, this then becomes the default Item Variation Data index for not only the Private DICT, but also all CharStrings that reference that Private DICT, until the vsindex operator is used again.

Syntax for Font Variations support operators.

vsindex ivs vsindex (22)

Sets the scalars for blending a set of delta values, using the itemVariationData index specified by the unsigned integer index ivs. The index ivs is interpreted as a variation store itemVariationData index for the VariationStore structure. If the vsindex operator is not present in a Private DICT, then the default value is vsindex value is 0. When present, it must be the first operator in the Private DICT. It also sets the default vsindex value for all CharStrings that reference the Private DICT.

blend num(0,0)...num(0,n-1), num(0,0)...num(k-1,0)… num(0,n-1)...num(k-1,n-1) n blend (23) val(0)...val(n-1)

for k delta value operands, produces n interpolated result value(s) from n*k arguments.

The blend operator uses the same set of delta values as used in the TrueType blending model. n is the number of values that will be left on the stack for the next operator. This is passed as the last argument on the stack, and lets the blend operator know that it is preceeded by n+1 groups of operands. The first group contains n arguments that are the actual n values on the stack from the default design. The following n groups each contain k delta values, where k is the number of regions other than the default design. In each of these following groups, the num(i,j) value is for item j on the default design operand stack, and is the delta value for region k. For example, consider an rmoveto operator in a glyph with 3 master source designs and and two design axes, Weight and Width, where the ‘Light’ master source design is used to provide the default design, and ‘Bold’ and ‘Condensed’ are used to provide the regions and delta values for the Bold and Condensed regions.

- 100 150 rmoveto ‘Light’ default design (Weight = 0, Width = 0)

- 100 300 rmoveto ‘Bold’ design (Weight = 1, Width = 0)

- 50 100 rmoveto ‘Condensed’ design (Weight = 0, Width = 1)

The first group of arguments are the n values from the default design:

- 100 150

For each following group i for i = 0 to n-1, the values are for stack element i for from each design other than the default. Parentheses are added here to denote each group.

- (100 150) (100 50) (300 100) 2 blend rmoveto

The actual arguments in the groups after the first group are delta values, rather than the actual design values: the difference between the value for the region and the default design value:

- (100 150) (0 -50) (150 -50) 2 blend rmoveto.

See the chapter OpenType Font Variations Overview for a full discussion of the calculation of delta values, which is usually more complex than shown in this simple case.

Appendix A. CFF 2 Charstring Command Codes

One-byte CFF 2 Operators

| Dec | Hex | Operator | Dec | Hex | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00 | —Reserved— | 18 | 12 | hstemhm |

| 1 | 01 | hstem | 19 | 13 | hintmask |

| 2 | 02 | —Reserved— | 20 | 14 | cntrmask |

| 3 | 03 | vstem | 21 | 15 | rmoveto |

| 4 | 04 | vmoveto | 22 | 16 | hmoveto |

| 5 | 05 | rlineto | 23 | 17 | vstemhm |

| 6 | 06 | hlineto | 24 | 18 | rcurveline |

| 7 | 07 | vlineto | 25 | 19 | rlinecurve |

| 8 | 08 | rrcurveto | 26 | 1a | vvcurveto |

| 9 | 09 | —Reserved— | 27 | 1b | hhcurveto |

| 10 | 0a | callsubr | 282 | 1c | shortint |

| 11 | 0b | return | 29 | 1d | callgsubr |

| 121 | 0c | escape | 30 | 1e | vhcurveto |

| 13 | 0d | —Reserved— | 31 | 1f | hvcurveto |

| 14 | 0e | —Reserved— | 32–246 | 20–f6 | <numbers> |

| 15 | 0f | vsindex | 247–2543 | f7–fe | <numbers> |

| 16 | 10 | blend | 2554 | ff | <number> |

| 17 | 11 | —Reserved— |

- 1. First byte of a 2-byte operator.

- 2. First byte of a 3-byte sequence specifying a number.

- 3. First byte of a 2-byte sequence specifying a number.

- 4. First byte of a 5-byte sequence specifying a number.

Two-byte CFF 2 Operators

Note 6. CFF 2 Charstrings do not support any of the arithmetic, storage, or conditional operators that are supported by Type 2 CharStrings.

| Dec | Hex | Operator | Dec | Hex | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 0 | 0c 00 | —Reserved— | 12 20 | 0c 14 | —Reserved— |

| 12 1 | 0c 01 | —Reserved— | 12 21 | 0c 15 | —Reserved— |

| 12 2 | 0c 02 | —Reserved— | 12 22 | 0c 16 | —Reserved— |

| 12 3 | 0c 03 | —Reserved— | 12 23 | 0c 17 | —Reserved— |

| 12 4 | 0c 04 | —Reserved— | 12 24 | 0c 18 | —Reserved— |

| 12 5 | 0c 05 | —Reserved— | 12 25 | 0c 19 | —Reserved— |

| 12 6 | 0c 06 | —Reserved— | 12 26 | 0c 1a | —Reserved— |

| 12 7 | 0c 07 | —Reserved— | 12 27 | 0c 1b | —Reserved— |

| 12 8 | 0c 08 | —Reserved— | 12 28 | 0c 1c | —Reserved— |

| 12 9 | 0c 09 | —Reserved— | 12 29 | 0c 1d | —Reserved— |

| 12 10 | 0c 0a | —Reserved— | 12 30 | 0c 1e | —Reserved— |

| 12 11 | 0c 0b | —Reserved— | 12 31 | 0c 1f | —Reserved— |

| 12 12 | 0c 0c | —Reserved— | 12 32 | 0c 20 | —Reserved— |

| 12 13 | 0c 0d | —Reserved— | 12 33 | 0c 21 | —Reserved— |

| 12 14 | 0c 0e | —Reserved— | 12 34 | 0c 22 | hflex |

| 12 15 | 0c 0f | —Reserved— | 12 35 | 0c 23 | flex |

| 12 16 | 0c 10 | —Reserved— | 12 36 | 0c 24 | hflex1 |

| 12 17 | 0c 11 | —Reserved— | 12 37 | 0c 25 | flex1 |

| 12 18 | 0c 12 | —Reserved— | 12 38 – 12 255 | 0c26 – 0cff | —Reserved— |

| 12 19 | 0c 13 | —Reserved— |

Appendix B. CFF 2 Charstring Implementation Limits

The following are the implementation limits of the CFF 2 charstring interpreter:

| Description | Limit |

|---|---|

| Argument stack | 1931 |

| Number of stem hints (H/V total) | 96 |

| Subr nesting, stack limit | 10 |

| Charstring length | 65535 |

| maximum (g)subrs count | 65536 |

| TransientArray elements | 32 |

- 1. The max argument stack is a default value; it may be increased by the maxstack operator in the CFF 2 Top DICT. This operator may be used only once, and will set the max stack value for all charstrings in the font.There is some current Adobe font data which requires a maxstack of 513, for glyphs which have 512 master designs, and leave only one blended value on the stack.

Appendix C. Compatibility and Deprecated Operators

CFF 2 CharStrings may not be used with CFF font tables. The CFF 2 CharStrings will be missing the endchar and return operators required by Type 2 CharStrings, and do not provide the width values that are required by CFF 1.0 font tables. In addition, CFF 2 Charstrings may include operators (blend and vsindex) that are not supported by interpreters for CFF 1.0 font tables.

Appendix D Changes From Type 2 CharStrings

- CFF 2 CharStrings must not contain a value for width: a CFF 2 font table do not contain any CharString width data.

- For CFF 2 fonts, the fill rule for CharStrings must always be the nonzero winding number rule, rather than the even-odd rule.

- The default maximum stack depth allowed is increased from 48 to 193.

- The CharString operator set is extended in CFF 2 to include the blend and vsindex operators. These work as described above in section 4.5 Variation Data Operators.The CFF 2 CharString operator code for blend is 16, and 15 for vsindex.

- The Type 2 operators endchar and return are removed.

- The Type 2 logic, storage, and math operators are removed.

Appendix E Changes Since Earlier Versions

The following changes and revisions have been made since the initial publication date of 8 August 2016.

- Initial publication of document: 6 September 2016. See Appendix D Changes From Type 2 CharStrings.

OpenType specification