WCSF Application Architecture 6: Structuring Modules

This article is part of a series;

· WCSF Application Architecture 1: Introduction

· WCSF Application Architecture 2: Application Controller

· WCSF Application Architecture 3: Model View Presenter

· WCSF Application Architecture 4: Environment Abstraction

· WCSF Application Architecture 5: Defining Modules

Introduction

This post is intended to address some common scenarios when using the Web Client Software Factory, in particular relating to how modules should be structured internally, and how they should relate to each other... as with all my other posts, this is based on what I’ve done and what I’ve seen others do – I’m sure there are other ways out there, so please feel free to chip in if you have something to say, suggest, or disagree with.

I’m going to present architectural candidates for you to consider, and discuss why you might choose to use them, which I hope should give you ideas about how they might apply to your situation.

So, get comfortable, and read on!

For consistency with my previous post in this series, I will assume that initially we have some business modules (Customers, Accounts, and Orders) and a foundation module (Infrastructure). I’ll pick and choose from these to illustrate my points as we go.

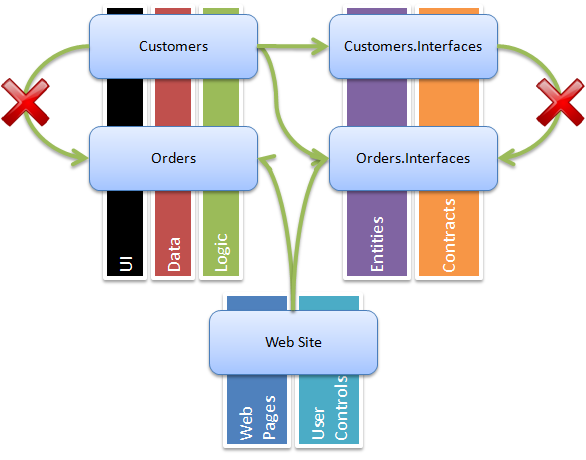

Model 1: Classic

I’ve named this model “Classic” as it is pretty much the basic use of the WCSF as it was intended;

Note: An arrow indicates a reference – so Customers has a project reference to Customers.Interfaces. The coloured bars indicate responsibilities for each project.

This diagram shows us a number of things;

1. The WCSF provides an out-of-the-box option to define an “interfaces” project for each module, in which the public “contract” of the module is defined. An “Interfaces” project contains contracts (i.e. for services a module exposes) and entities.

2. The Web Site contains the Web Pages and User Controls for a module.

3. The implementation projects (what I call the module projects that are not suffixed with “.interfaces”) contain the full remaining layers of the architectural stack, from UI (presenters etc) through business logic, to resource access.

4. The Web Site may reference both interface and implementation projects.

5. The implementation projects may reference their own or other modules’ “interfaces” projects. This allows modules to take dependencies on services exposed by other modules in a loosely coupled way.

6. As shown by the X marks, modules should not reference each other in any other way. Doing so would cause their implementations to be tightly coupled, and can cause circular references – which would be really bad news.

I’m a big believer in showing some code to demonstrate how this works, so let’s take a simple example and consider the following;

namespace Customers.Interfaces

{

public class Customer

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

public interface ICustomerService

{

List<Customer> GetCustomers();

}

}

namespace Customers

{

public class CustomerService : ICustomerService

{

public List<Customer> GetCustomers()

{

// implementation

}

}

}

Here we see the Customer entity and the ICustomerService contract are defined in the Customers.Interfaces project, and a real implementation of CustomerService in the implementation project. Obviously there would be IView definitions and Presenters in the implementation module too, and ASPX pages etc in the web site, but these are not relevant to this example.

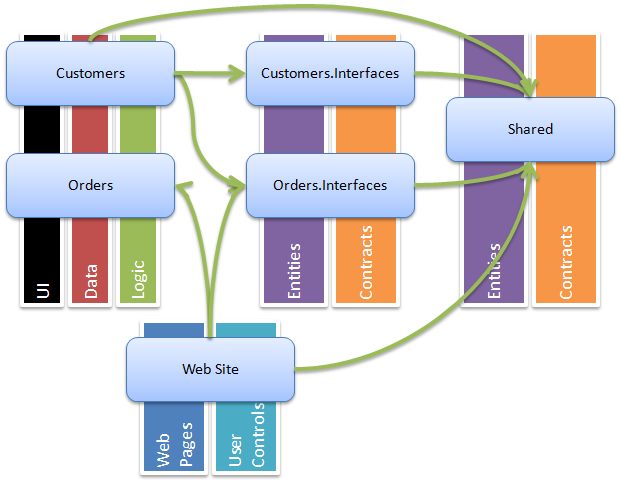

Model 2: Shared Entities

Model 1 is in many ways the ideal – but the problem is life is often more complicated than this! The first thing you’re likely to encounter is when two modules need to share the same entity. So consider what happens if I define the following (slightly contrived) contract in my Orders.Interfaces project;

namespace Orders.Interfaces

{

public class OrderDetails

{

public string OrderReference { get; set; }

}

public interface IOrderService

{

void PlaceOrder(Customer customer, OrderDetails order);

}

}

Looks great huh? Ah, but Customer is defined in Customers.Interfaces... I could add a reference from Orders.Interfaces to Customers.Interfaces, but how long would it be before I needed to do the same in reverse and had a circular reference?

This leads me to a piece of advice;

Avoid having references between “.interfaces” projects

Also, remember that in my previous article we discovered that it is good practice to ensure that one and only one module owns access to any particular data source. So we shouldn’t create two different customers entities. So what do we do?

This diagram has way too many arrows on it to indicate acceptable references, but I wanted to provide a complete view, so I apologise! Basically, then, this boils down to creating a separate shared project in which you put common entities and contracts. Entities that only relate to a single module can stay in that module’s interfaces project.

So in our example, this becomes as follows;

namespace Shared

{

public class Customer

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

}

namespace Customers.Interfaces

{

public interface ICustomerService

{

List<Customer> GetCustomers();

}

}

namespace Customers

{

public class CustomerService : ICustomerService

{

public List<Customer> GetCustomers()

{

// implementation

}

}

}

namespace Orders.Interfaces

{

public class OrderDetails

{

public string OrderReference { get; set; }

}

public interface IOrderService

{

void PlaceOrder(Customer customer, OrderDetails order);

}

}

You see that the Customer entity has moved out, and now we have no circular reference concerns.

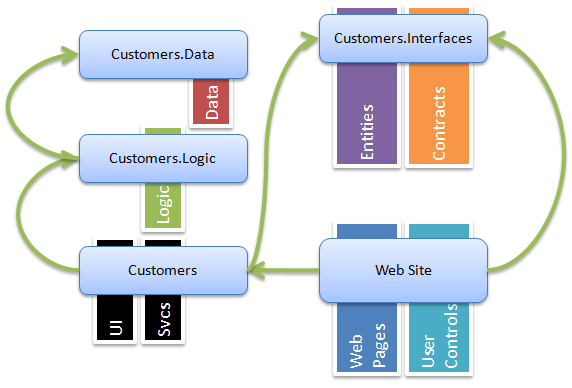

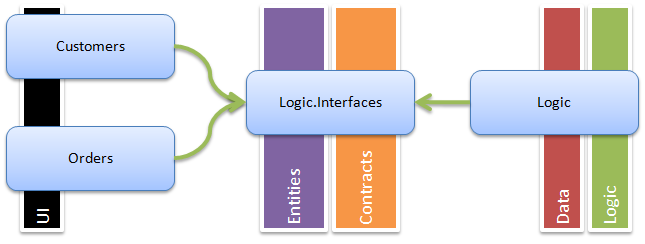

Model 3: Layered Modules

I have historically always separated my application layers by project – I find this helps keep the layering clear, and keeps the volume of code in any one project to a manageable level. The WCSF does not do this by default – but it doesn’t prevent you from doing it! In fact, some of the reference implementations split modules in a similar way;

This diagram shows that I have added two new standard C# projects to the solution, and named them Customers.Data and Customers.Logic (note I have omitted the Orders functionality here just to keep the diagram simple). My layers are now kept nice and separate. Each layer may reference the layer below, but not vice-versa.

Now there is an interesting point to make from this diagram – my Logic and Data projects have noreference to the Customers.Interfaces project. This means they cannot deal with the “Customer” entity!

I actually think this is a matter of choice – it depends on how much you wish to ensure your layers are loosely coupled. Using the approach I have taken, you would need to use an adapter or entity translation pattern in the Customers implementation project. Here, the UI facing classes (such as presenters or services) would translate between the outward facing entities defined in Customers.Interfaces, and those used internally by the module (perhaps database-focused entities). The services in the Customers module would simply act as a facade to real logic, contained in the Logic project.

The truth is, it can be a bit of a pain taking this approach, so you may wish to compromise – but the point is, it needs a few moments of thought. Choose an approach that you feel comfortable with and stick to it throughout your solution.

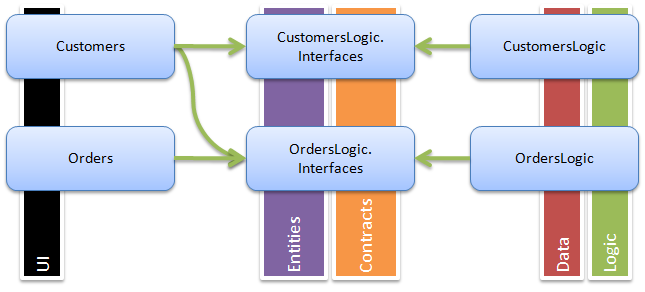

Model 4: Split Modules

An alternative approach to bringing extra clarity to your layering is to physically split up your modules;

Note: I have excluded the Web Site from this diagram, as I’m sure you’re getting the point!

Here you can see that we have Customers and Orders business modules, without matching interfaces projects. These only contain UI code, allowing you to keep the projects really focused. We then have two foundation modules – CustomersLogic and OrdersLogic (not very well named, I admit!). These modules expose services to the UI modules to allow them to access the “model” (as Model-View-Presenter) that is our business logic. The reference between the UI code and the business logic is loosely coupled as it goes via the foundation modules’ interfaces projects. If you really wanted, you could take this one step further and split the foundation modules into more projects as we discussed in the Layered Modules approach.

This is indeed very similar to the Layered Modules approach, except that it gives you an opportunity to deploy business logic separately to your user interface. This can have big benefits for team working (e.g. different teams working on the UI and business logic), or for deployment – perhaps your UI works for a number of systems, with different business logic plugged in behind?

Model 5: Split Master Logic Module

All of these approaches so far have one thing in common; they expect you to be able to vertically partition your code to some greater or lesser extent. In reality, this is the hardest bit of getting your WCSF implementation right – what parts of the system are really independent from each-other?

In particular, if you are migrating an existing system you may well find all of your business logic and data access is so tightly related, interlinked, and interdependent, that you cannot split it into modules without all sorts of circular references, shared entities, and so on. You could try, and end up with spaghetti dependencies between modules – even if it is loosely coupled, too many dependencies on each-other’s services is not a good sign. Or maybe you just happen to be building a small system that only really has one single area of functionality?

So all this means you could well end up with one single module, immediately losing some of the benefits to team working, componentisation, etc, that come with modularisation. Right?

Well, this is where the Split Master Logic Module approach comes in. Split your UI into modules – because that is often pretty easy - and then keep all your back end logic in a single foundation module that exposes services to the rest of your application;

I must make it clear that with this model you are missing out on the benefits of the complete vertical slice through your architecture you would get with a purist approach, but it does still have a place I believe.

This allows you to work in a loosely coupled way, modularising your UI (including independent deployment of modules if you wish), yet maximising the reuse of any existing business logic you have – it could be as simple as surfacing existing code as WCSF application services. You of course still have all the flexibility of a loosely coupled architecture too, so should you wish to migrate your existing code to a new, more modular architecture, just plug-and-play different service implementations as time goes by.

Conclusion

Well, that’s it – a lightning fast tour of some approaches to splitting your modules up. Have I missed an approach? Have you come up with something better? Do you hate one of the approaches above? As always, shout up and let me know.

The one approach I haven’t discussed is using a Service Layer to physically split the UI from a logic tier. Watch this space and I’ll try to post some thoughts on this soon.

Finally, I threw a few comments into the text above that might have got you thinking... if so, check out;

· The Adapter pattern

· Entity Translation – best explained by Don Smith, in context of the Web Service Software Factory but relevant to us too!

· My thoughts on LINQ solution structures (aimed at a WPF app, but some relevance to the web)

Enjoy!

Comments

- Anonymous

July 15, 2008

Great article about a topic which is important for every application developer! You write "Avoid having references between “.interfaces” projects" because of circle dependencies. I slighty disagree with that and would prefer to follow a strict design pattern: Entities and references between Entities should be designed in a strict hierarchy:

- Independent Entities can't have object references to dependent Entities.

- Dependent Entities can have object references to independent Entities. Example Entity Hirarchy:

- Customer is independent.

- Order is dependent of Customer. Example References:

- Order can have a OBJECT reference to Customer.

- Customer CAN'T have OBJECT references to Order. Instead, the order service provides a method to get all orders for a customer. By following this schema, circle references never appear.

Anonymous

July 15, 2008

Bernhard; I agree with you - this kind of scheme makes a lot of sense, especially if you put your "independent entities" in a seperate shared project (the same as I describe in the "Shared Entities" approach); this has the result of combining two approaches. I guess my only concern with this would be that entities are not necessarily always in a single place, and it could cause a little confusion. Having said that, I think it is likely the "shared" entities would be pretty special ones, so chances are it would turn out fine. Anyway, interesting comments, thanks! Has anyone else used the approach Bernhard mentions? SimonAnonymous

July 16, 2008

If one does not want to use Translators, the shared approach is the only solution for having independent modules. The most correct way would be that each module has its own entity-definitions and calls other services for retrieving data. the translator then must map between the different entities. But this seems to me a big overhead in many projects....Anonymous

July 16, 2008

... or you could have shared interfaces only, implemented as an entity in each module. I blogged something similar to that (although not using the WCSF) under the LINQ solution structures link above. I agree with your overheads comment - I often think that pragmatism is one of the most rare yet most valuable attributes for software architects and designers! Oh, I guess I got your name the wrong way round above too - sorry :-) SimonAnonymous

November 20, 2008

This article is part of a series; · WCSF Application Architecture 1: Introduction · WCSF ApplicationAnonymous

November 20, 2008

The comment has been removedAnonymous

November 24, 2008

@ Egil, OK, I'll do my best!! What you describe about your entities is pretty common, and I think you have two main options.

- Keep them all together, and use my "Split Master Logic Module" model; That is, a single foundation module that handles all logic and data access. This means you can modularise your UI as much as you like without worrying about where to put your entities.

- Split your entities into modules; You can then use projection so that they are not exposed from modules that don't own them. For example, if you have a Sales module and a Customers module (probably bad examples to be honest, but stick with this!), the Sales module would own the "Deal" entity, and the Customers module would own the "Person" entity. But when retrieving a list of deals you need to see customer name, right? So create a new entity used only for UI rendering named "DealInfo" (or something like that). This should contain all the data a deal includes, and a customer name field from the Person table. Then, in your business logic, when retrieving the data you use LINQ projection as follows; var result = from p in db.Persons join d in db.Deals on p.Id equals d.PersonId select new DealInfo() { DealId = d.Id, DealValue = d.Value, CustomerName = p.Name }; Therefore you never expose your "Person" entity from within the Deals module, only the data you chose as relevant. This does mean both modules access some of the same resources, so it needs to be a judgement call from you as to how much this matters. It isn't ideal, but software is often about making pragmatic trade-offs. Does that help? For handling LINQ to SQL for change tracking, check out this great blog post; http://borrell.parivedasolutions.com/2008/02/linq-to-sql-updating-in-aspnet-right.html The trick is to use a timestamp column for optimisitic concurrency. Brian also uses a neat trick of serialising the entity into ViewState (although you could use other mediums) before re-attaching it on post-back. I wouldn't advise keeping the data context cached - in a multi-user web app scenario you want it to be fairly short-lived, submitting your changes with each page update. I'm not even sure you can store a DataContext in session state - chances are it isn't serialisable (although I've not checked). Hope that helps. Simon

Anonymous

November 24, 2008

Hi Simon Thank you for your reply. It did indeed confirm many of the thoughts I have been having the last few days. In general though, it is a bit unclear to me if there is a "right" approach to splitting modules up without getting spaghetti dependencies between them, when using ORM. With ORM you naturally get a object hierarchy, which doesn't fit in this pattern. Or is it just me that is unable to see past the strict pattern structures? You get into it a little in your "LINQ solution structures" post, but your example is very limited (as you yourself point out). I would love to see you expand on that example, maybe in relation to WCSF/ASP.NET, it might help that light bulb go of in my brain :) In regards to LINQ to SQL and object tracking. When I talked about unit of work in relation to L2S, I was mostly inspired by Marcos post on it: http://www.codemetropolis.com/archive/2008/05/20/linq-to-sql-in-real-word-web-applications.aspxAnonymous

November 30, 2008

@ egil; I agree - this is difficult stuff. This is exactly why I have a rule of thumb; "Make sure a single module owns access to any given resource." (from http://blogs.msdn.com/simonince/archive/2008/06/19/wcsf-application-architecture-5-defining-modules.aspx) A database is just a resource, so unless you can split your database I'd generally prefer to keep access to it owned by a single module. This is why I suggested the "Split Master Logic Module" approach above. It keeps your entities together, but allows you to modularise your UI. The problem with that is sometimes it's nice to break the rules slightly for the sake of better modularity, and performance, hence my advice above... I say performance because you could split your entities and have ModuleA call ModuleB to get the customer's name for each row it returns. This potentially results in massively increased database or web service calls though. The rule-breaking approach does mean your modules have back-end mixed dependencies which can be a versioning and deployment headache, though, so be careful. I think basically the answer is, if you're struggling to split your entities into logical groups, maybe you shouldn't! One day, when I get some free time, maybe I'll put together some more details samples - but being completely honest I can't see that happening sometime soon! I also think the Reference Implementation from the p&p guys is a good starter... Hope that helps, SimonAnonymous

December 05, 2008

Thanks for this excellent series on the WCSF. Having worked on large scale custom framewoeks, it's good to see software engineering concepts & best practices collated into an integrated re-usable offering from the microsoft.Anonymous

December 07, 2008

@msingh; thanks for the feedback! Really pleased you're finding it useful. Simon