C# 4 expressions: blocks [Part I]

Since .Net 3.5 and Linq, the C# compiler is capable of generating expression trees instead of standard executable IL. Even if Linq opens the door of meta-programming (using the code to define something else, like a Sql query), we still have a lot of limitations.

A C# expression is limited to a single instruction returning a value, given some parameters. Method calls, properties access, constructors, and operators are allowed but no block, no loops, etc…

Expression<Action<string>> printExpression =

s => Console.WriteLine(s);

var Print = printExpression.Compile();

Print("Hello !!!");

Of course, compiling the expression is not the only final goal but I will not go further in this article.

With .Net 4.0, Linq expressions implementation has moved to the DLR. The dynamic language runtime is using a richer expression API that allows a lot of thing. We can consider that C# 4.0 compiler is using a subset of the DLR expressions.

So, even if C# 4.0 now allows expressions based on Actions, we still have all the other limitations.

Therefore we can use the expression API programmatically to express more complex expressions like explained in this post from Alexandra Rusina. But we won’t be able to express those complex expressions from the C# language.

Let’s try to find a work around for the first big barrier: statements…

The new expression API offers the BlockExpression class to define a block of statements.

It’s quite easy to use since we just have to provide a list of expressions.

public static BlockExpression Block(params Expression[] expressions);

We will notice that we can also provide a list of variables if needed but I will come back to this point a little bit later in this article.

So the first very big restriction is we can only provide one single instruction !

Now imagine we use a syntax comparable to the one explained in this article where some instance methods always return the instance itself (this) so we can create a sequence of them.

public class Block

{

public Block _(Action action)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public static Block Default

{ get; private set; }

I know it’s very strange but I’ve chosen to name my method “_”. It’s authorized by C# and it’s legal :)

I have also defined a Default property to avoid to have to create Block instances every time and because it’s an easy signature to recognize.

Now we can write things like:

Expression<Action<string>> exp = s =>

Block.Default

._(() => Console.WriteLine("I"))

._(() => Console.WriteLine("would like"))

._(() => Console.WriteLine("to say: "))

._(() => Console.WriteLine(s));

Now the whole expression is correct because we have a single instruction but it defines a collection of actions and each of them contains a single instruction again.

You can notice that there is only one “;” in my code.

Of course, my idea is to use this strange syntax to transform this expression into a BlockExpression. To achieve this I have to analyze my expression, find the Block.Default signature, remove it, and then extract the body from all the actions to finally get the collection of expressions to build my BlockExpression.

To do this, I have implemented an expression visitor. You can notice that the base class is now part of .Net (through the DLR once again): System.Linq.Expressions.ExpressionVisitor.

The visitor is a massively recursive code that helps you analyze all the possible nodes of an expression tree. For this first step, I will override the VisitMethodCall method to catch my sequence of Block methods.

protected override Expression VisitMethodCall(MethodCallExpression node)

{

if (IsMethodOf<Block>(node))

{

var expressions = new List<Expression>();

do

{

var r = VisitBlockMethodCall(

node as MethodCallExpression);

expressions.Insert(0, r);

node = node.Object as

MethodCallExpression;

} while (node != null);

return Expression.Block(expressions);

}

return base.VisitMethodCall(node);

}

As method calls are in sequence, which is an unary operation, it’s possible to unrecursive this specific part of the visitor and that’s what I am doing in the do…while loop.

There is an important thing to know about method call sequences. The visitor is discovering them in the opposite order of the C# syntax.

For example, if I write :

test.Do().Print();

We will be discovering Print() first, then Do(). It’s quite logical because (test.Do()) will be the source from which Print() is called. The loop is going up the sequence while the source (node.Object) is still a MethodCallExpression (node != null). You can notice that the extracted actions bodies are inserted on top of the list to recreate the C# syntax order.

Of course we are doing all this work only if the method is declared by the Block type. The IsMethodOf helper method is used here.

private bool IsMethodOf<T>(MethodCallExpression node, string methodName)

{

if (node == null)

return false;

return ((node.Method.DeclaringType

== typeof(T))

&& (node.Method.Name == methodName));

}

private bool IsMethodOf<T>(MethodCallExpression node)

{

if (node == null)

return false;

return (node.Method.DeclaringType

== typeof(T));

}

For this first step, I am only looking for the “_” method but I will later add more features to the Block class. That’s why I have isolated the methods recognition is a separated method : VisitBlockMethodCall.

private Expression VisitBlockMethodCall(MethodCallExpression node)

{

if (IsMethodOf<Block>(node, "_"))

return Visit((node.Arguments[0] as

LambdaExpression).Body);

...

}

As I know the only argument is an Action (a lambda expression in our tree), I am just extracting the body and I do not forget to apply the Visitor on it before returning it (so the visitor logic can continue on this branch).

Once I have collected all those expressions, I just have to build and return Expression.Block(expressions). '”Block.Default” is naturally skipped at this moment.

Important point: all the Block members are not important in the end because there goal are to be removed by this transformation step. After the transformation, they must have all disappeared. I just consider them as markers for my transformation engine (metadata and not code). That’s also why they are never implemented (throw new NotImplementedException()). BUT whatever the transformation we make on the expression, it MUST respect the C# syntax in the first place.

Now we have to apply the visitor on our sample expression.

Expression<Action<string>> expWithBlock = s =>

Block.Default

._(() => Console.WriteLine("I"))

._(() => Console.WriteLine("Would like"))

._(() => Console.WriteLine("To say: "))

._(() => Console.WriteLine(s));

expWithBlock =

ExpressionHelper.Translate(expWithBlock);

expWithBlock.Compile()("Hello !!!");

public static class ExpressionHelper

{

public static Expression<TDelegate> Translate<TDelegate>(Expression<TDelegate> expression)

{

var visitor =

new BlockCompilerVisitor<TDelegate>();

return visitor.StartVisit(expression);

}

}

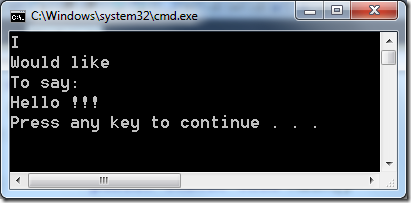

and we get

I this very first step we managed to create multiline C# expressions based on actions.

Visual Studio 2010 has a very useful new debug viewer for expressions that you can call at debug time.

Here is our expression before…

.Lambda #Lambda1<System.Action`1[System.String]>(System.String $s) {

.Call (.Call (.Call (.Call (CSharp4Expressions.Block.Default)._(.Lambda #Lambda2<System.Action>))._(.Lambda #Lambda3<System.Action>)

)._(.Lambda #Lambda4<System.Action>))._(.Lambda #Lambda5<System.Action>)

}

.Lambda #Lambda2<System.Action>() {

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("I")

}

.Lambda #Lambda3<System.Action>() {

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("Would like")

}

.Lambda #Lambda4<System.Action>() {

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("To say: ")

}

.Lambda #Lambda5<System.Action>() {

.Call System.Console.WriteLine($s)

}

…and after transformation.

.Lambda #Lambda1<System.Action`1[System.String]>(System.String $s) {

.Block() {

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("I");

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("Would like");

.Call System.Console.WriteLine("To say: ");

.Call System.Console.WriteLine($s)

}

}

It’s not finished but enough for a single post.

Next part will propose a solution for creating variables and then other expression API features like Loop, Goto, Label, Assign and even new features like For.

You can get the whole solution here: https://code.msdn.microsoft.com/CSharp4Expressions

Comments

Anonymous

March 02, 2010

Great article, looking forward for the rest of it. I had one question regarding generating IL in C#, I'm not a C# expert (I'm rather a UNIX/C dev) but some times ago I read an article about creating a compiled assembly and invoking it from the main code (basicaly generating C# code/compiling it and running it). If I remember correctly it was going like this: in brief I'm sure you'll understand. CompilerParameters.... (adding the needed dlls) using stringbuilder create C# code with append method. then calling CompileAssemblyFromSource to create the compiled version, getting the compiled assembly through CompiledAssembly (from the return of CompileAssemblyFromSource). Then you only need to call CreateInstance and invoke it. a bit like this in fact ;) http://www.codeproject.com/KB/cs/evalcscode.aspx Although I understand that you can now do it through linq (and it's meta language) I'd like to know what are the benefits from the other method.Anonymous

March 02, 2010

Hi Irsla, Ok, in my sample, I have only used my expressions to compile then into IL. It was just to demonstrate it was correct. But the goal of metaprogramming is to transform such expressions into something else like GPU instructions, javascript, maybe stored procedure or anything else.Anonymous

March 06, 2010

It's a shame this kind of expression "building" is required rather than the compiler teams having provided support for turning method bodies into full expression trees for us. While this works, there's no doubt that writing the method in "natural" C# syntax would have been leaps and bounds better. For example, we could have had full on CUDA/OpenCL support in C# immediately with very little extra work. I actually blogged about this when I first learned about full support coming to the Expression API[1]. I'm still hopeful that the compiler team(s) will work to provide this support in a .NET 4.5 release or something. fingers crossed [1] http://blog.hackedbrain.com/archive/2009/08/24/6174.aspxAnonymous

March 07, 2010

Drew, of course I agree with you but it's quite a big design to add this to C# (and VB if we want to make it clean). I would have love to see an easy transformation from C# to CUDA, Direct Compute, etc... Next version maybe.Anonymous

March 16, 2010

Hi Drew, I talked to C# PMs about this (a lot of people ask similar questions). The response is that these scenarios may become possible as a part of the new "compiler as a service" concept. Whether it will be done by using expressions trees is a different question, though. But these problems are definitely considered by the C# team. http://channel9.msdn.com/pdc2008/TL16/Anonymous

March 16, 2010

Thanks Alexandra ! "Compiler as a service" may even offer much more: a full language support ! (creating class, methods, etc) But it's an approach different from an expression tree because it's more language related. Look forward to play with such a tool ! :)Anonymous

March 29, 2010

It may not be necessary to add full compile-to-expressions support in the C# compiler itself. It could be done by decompiling IL. A problem waiting to be solved if anyone has some spare time! :) http://stackoverflow.com/questions/2305988/is-there-a-library-that-can-decompile-a-method-into-an-expression-tree-with-suppAnonymous

March 29, 2010

IL is really more low level than C#, so it's extremely hard to rebuild an expression tree. In expressions, you have Linq, methods reslution, type inference, implicit casts, etc, that does not exist in IL because it's been solved by the compiler.Anonymous

March 30, 2010

The comment has been removedAnonymous

March 30, 2010

It is Wonderfull Idea for my projectsAnonymous

March 31, 2010

The comment has been removedAnonymous

April 01, 2010

I think there is a confusion. It does not mean every one need to do this. For example Linq To Sql implementation is really complex but using it is very simple...Anonymous

April 05, 2010

Some proof reading would make this article much less irritating to read.Anonymous

April 09, 2010

Why would we actually use this in the real world?Anonymous

April 11, 2010

For those interested in the ability to build expression trees directly from source code, I'd like to point to F#, another .net language which will be part of Visual Studio 2010. This language supports this feature, where it is called "quotations".Anonymous

April 12, 2010

I don't want to seem argumentative but you're not telling me why I need an expression tree in the first place.Anonymous

April 23, 2010

Seems like a load of unneeded, over-complicated nonsense to me.Anonymous

April 28, 2010

Yes, I may very well fire the clever architect that litters my codebase with this unreadable code; granted the usage may be a little more readable... ie: Linq2Sql :) I'll take readable, traceable code anyday over having debug this complex code.Anonymous

April 29, 2010

Dan & dabasejumper, I've been using expressions to a very large degree for well over a year now doing some very advanced stuff - and have been waiting for full expression trees as they open up a world of possibilities - esp in GPU computing, DSLs, dynamic objects, etc. It's not simple but it's not at all over complicated. Before criticising these sorts of things as complex, maybe think that someone other than yourself has found a problem that this solves very well. In any case, you dont have to use it.Anonymous

April 29, 2010

Fan, I understand your point, I don't have to use them. And probably won't have the need to in the near future. What I would love to see though is a problem in which is solved by the use of an expression tree.Anonymous

April 29, 2010

Consider this example: Animate((o)=>{ var objWidth =o.Width; var objHeight = o.Height; if (objWidth > objHeight) { o.Width = 50; o.Height = objHeight / (objWidth / 50); } else { o.Height = 50; o.Width = objWidth / (objHeight / 50); } }); If this was represented as an expression, then we could easily convert this strongly-typed C# code to Javascript (using our JavascriptExpressionParser), or ActionScript (using our ActionscriptExpressionParser). It's probably not the best example - I was going to use a LINQ-to-SQL example, but thought everyone would've seen enough of those.Anonymous

May 10, 2010

The comment has been removed