Circuit Breaker pattern

The Circuit Breaker pattern helps handle faults that might take varying amounts of time to recover from when an application connects to a remote service or resource. A circuit breaker temporarily blocks access to a faulty service after it detects failures. This action prevents repeated unsuccessful attempts so that the system can recover effectively. This pattern can improve the stability and resiliency of an application.

Context and problem

In a distributed environment, calls to remote resources and services can fail because of transient faults. Transient faults include overcommitted or temporarily unavailable resources, slow network connections, or time-outs. These faults typically correct themselves after a short period of time. To help manage these faults, you should design a cloud application to use a strategy, such as the Retry pattern.

Unanticipated events can create faults that take longer to fix. These faults can range in severity from a partial loss of connectivity to a complete service failure. In these situations, an application shouldn't continually retry an operation that's unlikely to succeed. Instead, the application should quickly recognize the failed operation and handle the failure accordingly.

If a service is busy, failure in one part of the system might lead to cascading failures. For example, you can configure an operation that invokes a service to implement a time-out. If the service fails to respond within this period, the operation replies with a failure message.

However, this strategy can block concurrent requests to the same operation until the time-out period expires. These blocked requests might hold critical system resources, such as memory, threads, and database connections. This problem can exhaust resources, which might fail other unrelated parts of the system that need to use the same resources.

In these situations, an operation should fail immediately and only attempt to invoke the service if it's likely to succeed. To resolve this problem, set a shorter time-out. But ensure that the time-out is long enough for the operation to succeed most of the time.

Solution

The Circuit Breaker pattern helps prevent an application from repeatedly trying to run an operation that's likely to fail. This pattern enables the application to continue running without waiting for the fault to be fixed or wasting CPU cycles on determining that the fault is persistent. The Circuit Breaker pattern also enables an application to detect when the fault is resolved. If the fault is resolved, the application can try to invoke the operation again.

Note

The Circuit Breaker pattern serves a different purpose than the Retry pattern. The Retry pattern enables an application to retry an operation with the expectation that it eventually succeeds. The Circuit Breaker pattern prevents an application from performing an operation that's likely to fail. An application can combine these two patterns by using the Retry pattern to invoke an operation through a circuit breaker. However, the retry logic should be sensitive to any exceptions that the circuit breaker returns and stop retry attempts if the circuit breaker indicates that a fault isn't transient.

A circuit breaker acts as a proxy for operations that might fail. The proxy should monitor the number of recent failures and use this information to decide whether to allow the operation to proceed or to return an exception immediately.

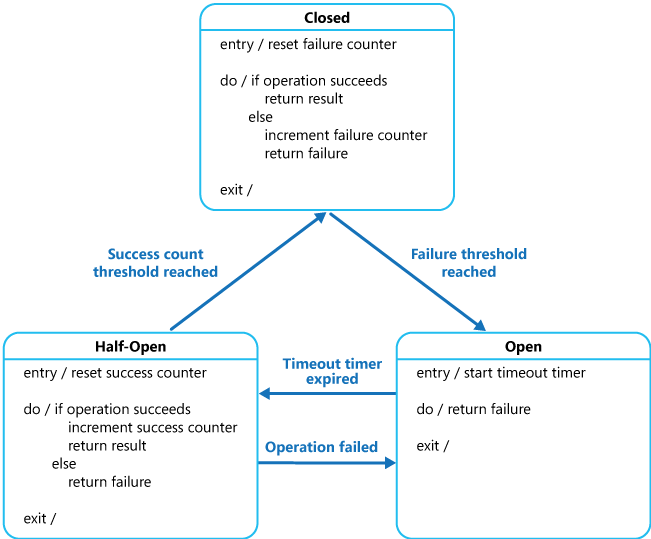

You can implement the proxy as a state machine that includes the following states. These states mimic the functionality of an electrical circuit breaker:

Closed: The request from the application is routed to the operation. The proxy maintains a count of the number of recent failures. If the call to the operation is unsuccessful, the proxy increments this count. If the number of recent failures exceeds a specified threshold within a given time period, the proxy is placed into the Open state and starts a time-out timer. When the timer expires, the proxy is placed into the Half-Open state.

Note

During the time-out, the system tries to fix the problem that caused the failure before it allows the application to attempt the operation again.

Open: The request from the application fails immediately and an exception is returned to the application.

Half-Open: A limited number of requests from the application are allowed to pass through and invoke the operation. If these requests are successful, the circuit breaker assumes that the fault that caused the failure is fixed, and the circuit breaker switches to the Closed state. The failure counter is reset. If any request fails, the circuit breaker assumes that the fault is still present, so it reverts to the Open state. It restarts the time-out timer so that the system can recover from the failure.

Note

The Half-Open state helps prevent a recovering service from suddenly being flooded with requests. As a service recovers, it might be able to support a limited volume of requests until the recovery is complete. But while recovery is in progress, a flood of work can cause the service to time out or fail again.

The following diagram shows the counter operations for each state.

The failure counter for the Closed state is time based. It automatically resets at periodic intervals. This design helps prevent the circuit breaker from entering the Open state if it experiences occasional failures. The failure threshold triggers the Open state only when a specified number of failures occur during a specified interval.

The success counter for the Half-Open state records the number of successful attempts to invoke the operation. The circuit breaker reverts to the Closed state after a specified number of successful, consecutive operation invocations. If any invocation fails, the circuit breaker enters the Open state immediately and the success counter resets the next time it enters the Half-Open state.

Note

System recovery is based on external operations, such as restoring or restarting a failed component or repairing a network connection.

The Circuit Breaker pattern provides stability while the system recovers from a failure and minimizes the impact on performance. It can help maintain the response time of the system. This pattern quickly rejects a request for an operation that's likely to fail, rather than waiting for the operation to time out or never return. If the circuit breaker raises an event each time it changes state, this information can help monitor the health of the protected system component or alert an administrator when a circuit breaker switches to the Open state.

You can customize and adapt this pattern to different types of failures. For example, you can apply an increasing time-out timer to a circuit breaker. You can place the circuit breaker in the Open state for a few seconds initially. If the failure isn't resolved, increase the time-out to a few minutes and adjust accordingly. In some cases, rather than returning a failure and raising an exception, the Open state can return a default value that's meaningful to the application.

Note

Traditionally, circuit breakers relied on preconfigured thresholds, such as failure count and time-out duration. This approach resulted in a deterministic but sometimes suboptimal behavior.

Adaptive techniques that use AI and machine learning can dynamically adjust thresholds based on real-time traffic patterns, anomalies, and historical failure rates. This approach improves resiliency and efficiency.

Problems and considerations

Consider the following factors when you implement this pattern:

Exception handling: An application that invokes an operation through a circuit breaker must be able to handle the exceptions if the operation is unavailable. Exception management is based on the application. For example, an application might temporarily degrade its functionality, invoke an alternative operation to try to perform the same task or obtain the same data, or report the exception to the user and ask them to try again later.

Types of exceptions: The reasons for a request failure can vary in severity. For example, a request might fail because a remote service crashes and requires several minutes to recover, or because an overloaded service causes a time-out. A circuit breaker might be able to examine the types of exceptions that occur and adjust its strategy based on the nature of these exceptions. For example, it might require a larger number of time-out exceptions to trigger the circuit breaker to the Open state compared to the number of failures caused by the unavailable service.

Monitoring: A circuit breaker should provide clear observability into both failed and successful requests so that operations teams can assess system health. Use distributed tracing for end-to-end visibility across services.

Recoverability: You should configure the circuit breaker to match the likely recovery pattern of the operation that it protects. For example, if the circuit breaker remains in the Open state for a long period, it can raise exceptions even if the reason for the failure is resolved. Similarly, a circuit breaker can fluctuate and reduce the response times of applications if it switches from the Open state to the Half-Open state too quickly.

Failed operations testing: In the Open state, rather than using a timer to determine when to switch to the Half-Open state, a circuit breaker can periodically ping the remote service or resource to determine whether it's available. This ping can either attempt to invoke a previously failed operation or use a special health-check operation that the remote service provides. For more information, see Health Endpoint Monitoring pattern.

Manual override: If the recovery time for a failing operation is extremely variable, you should provide a manual reset option that enables an administrator to close a circuit breaker and reset the failure counter. Similarly, an administrator can force a circuit breaker into the Open state and restart the time-out timer if the protected operation is temporarily unavailable.

Concurrency: A large number of concurrent instances of an application can access the same circuit breaker. The implementation shouldn't block concurrent requests or add excessive overhead to each call to an operation.

Resource differentiation: Be careful when you use a single circuit breaker for one type of resource if there might be multiple underlying independent providers. For example, in a data store that contains multiple shards, one shard might be fully accessible while another experiences a temporary problem. If the error responses in these scenarios are merged, an application might try to access some shards even when failure is likely. And access to other shards might be blocked even though it's likely to succeed.

Accelerated circuit breaking: Sometimes a failure response can contain enough information for the circuit breaker to trip immediately and stay tripped for a minimum amount of time. For example, the error response from a shared resource that's overloaded can indicate that the application should instead try again in a few minutes, instead of immediately retrying.

Multiregion deployments: You can design a circuit breaker for single region or multiregion deployments. To design for multiregion deployments, use global load balancers or custom region-aware circuit breaking strategies that help ensure controlled failover, latency optimization, and regulatory compliance.

Service mesh circuit breakers: You can implement circuit breakers at the application layer or as a cross-cutting, abstracted feature. For example, service meshes often support circuit breaking as a sidecar or as a standalone capability without modifying application code.

Note

A service can return HTTP 429 (too many requests) if it's throttling the client or HTTP 503 (service unavailable) if the service isn't available. The response can include other information, such as the anticipated duration of the delay.

Failed request replay: In the Open state, rather than simply failing quickly, a circuit breaker can also record the details of each request to a journal and arrange for these requests to be replayed when the remote resource or service becomes available.

Inappropriate time-outs on external services: A circuit breaker might not fully protect applications from failures in external services that have long time-out periods. If the time-out is too long, a thread that runs a circuit breaker might be blocked for an extended period before the circuit breaker indicates that the operation failed. During this time, many other application instances might also try to invoke the service through the circuit breaker and tie up numerous threads before they all fail.

Adaptability to compute diversification: Circuit breakers should account for different compute environments, from serverless to containerized workloads, where factors like cold starts and scalability affect failure handling. Adaptive approaches can dynamically adjust strategies based on the compute type, which helps ensure resilience across heterogeneous architectures.

When to use this pattern

Use this pattern when:

You want to prevent cascading failures by stopping excessive remote service calls or access requests to a shared resource if these operations are likely to fail.

You want to route traffic intelligently based on real-time failure signals to enhance multiregion resilience.

You want to protect against slow dependencies so that you can maintain your service-level objectives and avoid performance degradation from high-latency services.

You want to manage intermittent connectivity problems and reduce request failures in distributed environments.

This pattern might not be suitable when:

You need to manage access to local private resources in an application, such as in-memory data structures. In this environment, a circuit breaker adds overhead to your system.

You need to use it as a substitute for handling exceptions in the business logic of your applications.

Well-known retry algorithms are sufficient and your dependencies are designed to handle retry mechanisms. In this scenario, a circuit breaker in your application might add unnecessary complexity to your system.

Waiting for a circuit breaker to reset might introduce unacceptable delays.

You have a message-driven or event-driven architecture, because they often route failed messages to a dead letter queue for manual or deferred processing. Built-in failure isolation and retry mechanisms are often sufficient.

Failure recovery is managed at the infrastructure or platform level, such as with health checks in global load balancers or service meshes.

Workload design

Evaluate how to use the Circuit Breaker pattern in a workload's design to address the goals and principles covered in the Azure Well-Architected Framework pillars. The following table provides guidance about how this pattern supports the goals of each pillar.

| Pillar | How this pattern supports pillar goals |

|---|---|

| Reliability design decisions help your workload become resilient to malfunction and ensure that it recovers to a fully functioning state after a failure occurs. | This pattern helps prevent a faulting dependency from overloading. Use this pattern to trigger graceful degradation in the workload. Couple circuit breakers with automatic recovery to provide self-preservation and self-healing. - RE:03 Failure mode analysis - Transient faults - RE:07 Self-preservation |

| Performance Efficiency helps your workload efficiently meet demands through optimizations in scaling, data, and code. | This pattern avoids the retry-on-error approach, which can lead to excessive resource usage during dependency recovery and can overload performance on a dependency that's attempting recovery. - PE:07 Code and infrastructure - PE:11 Live-issues responses |

If this pattern introduces trade-offs within a pillar, consider them against the goals of the other pillars.

Example

This example implements the Circuit Breaker pattern to help prevent quota overrun by using the Azure Cosmos DB lifetime free tier. This tier is primarily for noncritical data and operates under a capacity plan that allocates a specific quota of resource units per second. During seasonal events, demand might exceed the provided capacity, which can result in 429 responses.

When demand spikes occur, Azure Monitor alerts with dynamic thresholds detect and proactively notify the operations and management teams that the database requires more capacity. Simultaneously, a circuit breaker that's tuned by using historical error patterns trips to prevent cascading failures. In this state, the application gracefully degrades by returning default or cached responses. The application informs users of the temporary unavailability of certain data while preserving overall system stability.

This strategy enhances resilience that aligns with business justification. It controls capacity surges so that workload teams can manage cost increases deliberately and maintain service quality without unexpectedly increasing operating expenses. After demand subsides or increased capacity is confirmed, the circuit breaker resets, and the application returns to full functionality that aligns with both technical and budgetary objectives.

Download a Visio file of this architecture.

Flow A: Closed state

The system operates normally, and all requests reach the database without returning any

429HTTP responses.The circuit breaker remains closed, and no default or cached responses are necessary.

Flow B: Open state

When the circuit breaker receives the first

429response, it trips to an Open state.Subsequent requests are immediately short-circuited, which returns default or cached responses and informs users of temporary degradation. The application is protected from further overload.

Azure Monitor receives logs and telemetry data and evaluates them against dynamic thresholds. An alert triggers if the conditions of the alert rule are met.

An action group proactively notifies the operations team of the overload condition.

After workload team approval, the operations team can increase the provisioned throughput to alleviate overload or delay scaling if the load subsides naturally.

Flow C: Half-Open state

After a predefined time-out, the circuit breaker enters a Half-Open state that permits a limited number of trial requests.

If these trial requests succeed without returning

429responses, the breaker resets to a Closed state, and normal operations restore back to Flow A. If failures persist, the breaker reverts to the Open state, or Flow B.

Components

Azure App Service hosts the web application that serves as the primary entry point for client requests. The application code implements the logic that enforces circuit breaker policies and delivers default or cached responses when the circuit is open. This architecture helps prevent overload on downstream systems and maintain the user experience during peak demand or failures.

Azure Cosmos DB is one of the application's data stores. It serves noncritical data via the free tier, which is ideal for small production workloads. The circuit breaker mechanism helps limit traffic to the database during high-demand periods.

Azure Monitor functions as the centralized monitoring solution. It aggregates all activity logs to help ensure comprehensive, end-to-end observability. Azure Monitor receives logs and telemetry data from App Service and key metrics from Azure Cosmos DB (like the number of

429responses) for aggregation and analysis.Azure Monitor alerts weigh alert rules against dynamic thresholds to identify potential outages based on historical data. Predefined alerts notify the operations team when thresholds are breached.

Sometimes, the workload team might approve an increase in provisioned throughput, but the operations team anticipates that the system can recover on its own because the load isn't too high. In these cases, the circuit breaker time-out elapses naturally. During this time, if the

429responses cease, the threshold calculation detects the prolonged outages and excludes them from the learning algorithm. As a result, the next time an overload occurs, the threshold waits for a higher error rate in Azure Cosmos DB, which delays the notification. This adjustment allows the circuit breaker to handle the problem without an immediate alert, which improves cost and operational efficiency.

Related resources

The Reliable Web App pattern applies the Circuit Breaker pattern to web applications that converge on the cloud.

The Retry pattern describes how an application can handle anticipated temporary failures when it tries to connect to a service or network resource by transparently retrying an operation that previously failed.

The Health Endpoint Monitoring pattern describes how a circuit breaker can test the health of a service by sending a request to an endpoint that the service exposes. The service should return information that indicates its status.