Single-sign-on between on-premise apps, Windows Azure apps and Office 365 services.

A lot of people don’t realise there will be 2 very interesting features in Office 365 which makes connecting the dots with your on-premise environment and Windows Azure easy. The 2 features are directory sync and federation. It means you can use your AD account to access local apps in your on-premise environment; just like you always have. You can also use the same user account and login process to access Office 365 up in the cloud, and you could either use federation or a domain-joined application running in Azure to also use the same AD account and achieve single-sign-on.

Let’s take them all one at a time:

On-Premise

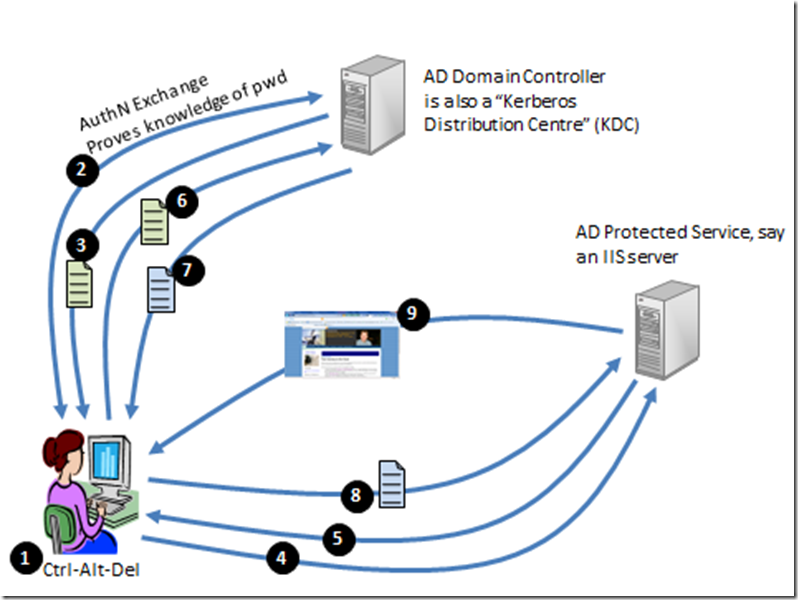

Not much to be said about these applications. If they are written to use integrated windows authentication, they’ll just work through the miracle that is Kerberos. It is worth reviewing, very briefly what happens with an on-premise logon, just to get an understanding of how the moving parts fit together.

Diagram 1: The AD Kerberos authentication exchange

Look at the numbered points in diagram 1 and follow along:

- The user hits Ctrl-Alt-Del and enters their credentials. This causes an…

- …authentication exchange between the client computer and the Domain Controller (which in Kerberos parlance is a Kerberos Distribution Centre or KDC). Note that the password itself never actually traverses the network, even in encrypted form. But the user proves to the KDC that they have knowledge of the password. If you want to understand more about how this is possible, read my crypto primer. A successful authentication results in…

- A Kerberos Ticket Granting Ticket or TGT being issued to the user. This will live in the user’s ticket-cache. I’ll explain this ticket using a real life example. In the 80s, my wife (girlfriend at the time) and I did a backpacking trip round China. In Guangzhou railway station we dutifully joined the long queue at the “Destination Shanghai” booth. Once at the head of the queue, the official said, effectively “Do you have your TGT?”. The answer was no – we wanted tickets to Shanghai. She informed us she couldn’t sell a ticket to Shanghai unless we had a “TGT” to give her. “How do you get one of those?” I asked and she pointed to an incredibly long queue. We joined that queue and eventually we were given a ticket; a “TGT”. This gave us the right to queue up at a booth to buy a train ticket. We then joined the “Destination Shanghai” queue again. When we got to the head of it, we exchanged our TGT (plus some money!) for a Shanghai ticket.

- Some time later, maybe hours later, the user tries to connect to IIS on a server.

- The server, requests a Kerberos Service Ticket (ST). This causes the client to…

- …send its TGT (which it could only have got by successfully authenticating and proving knowledge of the password) to the KDC. The KDC validates the TGT, and if succesful…

- ..issues a service ticket for the IIS server.

- The client forwards the service ticket to the IIS Server. The server has enough crypto material to check the validity of the service ticket. It effectively says “this is valid and there’s only one way you could have got it – you must have successfully authenticated at some stage. You are a friend!”. The result is…

- …the web page gets delivered to the user.

Extending the model to the cloud

Windows Azure Connect (soon to be released to CTP) allows you to not only create virtual private networks between machines in your on-premise environment and instances you have running in Windows Azure, but it also allows you to domain-join those instances to your local Active Directory. In that case, the model I described above works exactly the same, as long as Windows Azure Connect is configured in a way to allow the client computer to communicate with the web server (which is hosted as a domain-joined machine in the Windows Azure data centre). The diagram would look like this and you can followed the numbered points using the list above:

Diagram 2: Extending AD in to Windows Azure member servers

Office 365

Office 365 uses federation to “extend” AD in to the Office 365 Data Centre. If you know nothing of federation, I’d recommend you read my federation primer to get a feel for it.

The default way that Office 365 runs, is to use identities that are created by the service administrator through the MS Online Portal. These identities are stored in a directory service that is used by Sharepoint, Exchange and Lync. They have names of the form:

planky@plankytronixx.emea.microsoftonline.com

However if you own your own domain name you can configure it in to the service, and this might give you:

planky@plankytronixx.com

…which is a lot more friendly. The thing about MSOLIDs that are created by the service administrator, is that they store a password in the directory service. That’s how you get in to the service.

Directory Synchronization

However you can set up a service to automatically create the MSOLIDs in to the directory service for you. So if your Active Directory Domain is named plankytronixx.com then you can get it to automatically create MSOLIDs of the form planky@plankytronixx.com. The password is not copied from AD. Passwords are still mastered out of the MSOLID directory.

Diagram 3: Directory Sync with on-premise AD and Office 365

The first thing that needs to happen, is that user entries made in to the on-premise AD, need to have a corresponding entry made in to the directory that Office 365 uses to give users access. These IDs are known as Microsoft Online IDs or MSOLIDs. This is achieved through directory synchronization. Whether directory sync is configured or not – the MS Online Directory Service (MSODS) is still the place where passwords and password policy is managed. MS Online Directory Sync needs to be installed on-premise.

When a user uses either Exchange Online, Sharepoint Online or Lync, the Identities come from MSODS and authentication is performed by the identity platform. The only thing Directory Sync really does in this instance is to ease the burden on the administrator to use the portal to manually create each and every MSOLID.

One of the important fields that is synchronised from AD to the MSODS is the user’s AD ObjectGUID. This is a unique immutable identifier that we’ll come back to later. It’s rename safe, so although the username, UPN, First Name, Last Name and other fields may change, the ObjectGUID will never change. You’ll see why this is important.

The Microsoft Federation Gateway

I’ve written quite a few posts in my blog about Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS) 2.0 and Windows Azure’s AppFabric: Access Control Service (ACS). These are both examples of Security Token Services (STSes) and they enable federation. The Microsoft Federation Gateway (MFG) is a similar service. It’s not a general purpose feature for use with any service, any organisation, in the way ADFS 2.0 and AppFab:ACS are. It’s a federation service that is aimed specifically at MS Online Services. It is therefore much easier to configure as much of it is already done for you by the virtue of it being used for Office 365 only.

The MFG can federate with your on-premise ADFS Server. The authentication of the MSOLID will take place using the local Active Directory account in your on-premise AD. This will be done by Kerberos and the ADFS Server (which authenticates over Kerberos as detailed in diagram 1). Office 365 services are only delivered through MSOLIDs – setting up federation doesn’t change that. An MSOLID (which still exists in the MSODS) is the entity to which a mailbox or a Sharepoint site is assigned; the entity to which you might set the mailbox size or Sharepoint site size. It is not assigned to the AD account. Simply a collection of attributes from the AD account are synchronized to the MSOLID account. The key join-attribute, the attribute the identity platform uses to link a successful authentication from your on-premise AD, to the correct MSOLID, is the AD ObjectGUID. Remember this is synchronised from AD to MSODS. Let’s have a look at how this works. First a federation trust is set up between the MFG in the cloud and a local instance of ADFS you have installed that sits atop your AD:

Diagram 4: Federation trust: MFG (Cloud) to ADFS (on-premise)

This involves the exchange of certificates and URL information. To understand more about federation trusts, read my primer. Creating a federation trust is a one-time setup. If certificates expire, it may need to be reset. But each service, ADFS and the MFG, publish metadata URLs where information like certificates and URLs can be extracted from. This means as long as each service’s metadata is updated (such as expired certificates), the opposite, corresponding service can poll its federation partner regularly and get automatic updates.

Notice in Diagram 4 how the IdP – the Identity Provider, has now moved from the MS Online Services Identity Platform, to your local AD. That’s because the identity information that is actually used is from your AD. Let’s walk through the scenario, having removed some of the components for simplicity:

Diagram 5: Office 365 federated authentication – stage 1.

- The MSOLIDs that were synced in to the MSODS have mailboxes assigned to them. There is an internal linkage in Exchange Online between the MSOLID and the mailbox (or any other service/resource, such as Sharepoint Sites and MSOLIDs) owned by the MSOLID.

- The user in the on-premise environment has already logged in to AD and is in possession of a Kerberos TGT (see step 3 in Diagram 1). She attempts to open a mailbox in Exchange Online. Exchange Online notices the access request is un-authenticated.

- Exchange Online therefore redirects her browser to its local federation service, the MFG. Exchange Online only trusts the local MFG, it doesn’t have a trust relationship with any other federation service.

- The MFG notices this user is un-authenticated, so it redirects the user’s browser to their own local federation service – the ADFS server they have installed on-premise.

- As soon at the user hits the ADFS URL, the Kerberos authentication steps (steps 4 to 8 in Diagram 1) kick off to ensure only a user with a valid account and knowledge of the password can get access to its services. Note – at this point the user is not prompted for credentials because of the way Kerberos works (Diagram 1) but they do have authenticated access to ADFS. In this step, the user is requesting a SAML (Security Assertion Markup Language) Token. For more information on this, read the federation primer.

Diagram 6: Office 365 federated authentication – stage 2.

- Now the user is authenticated, the ADFS Server creates, encrypts and digitally signs a SAML Token which contains, among many other attributes, the user’s AD ObjectGUID.

- The user’s web browser is redirected, along with the signed and encrypted SAML Token back to the MFG. If you need to understand signatures and encryption, read the crypto primer.

- The MFG validates the signature on the incoming SAML token to ensure it did truly come from its federation partner. It decrypts the token and then creates a new token.

- Among many other attributes, it copies the AD ObjectGUID from the incoming SAML Token to the outgoing SAML Token. The SAML Token is signed and encrypted.

- The user’s web browser is now redirected, with the new SAML Token, to Exchange Online.

- Exchange Online validates the signature to ensure it was truly issued by the MFG, decrypts it and extracts among many other attributes the AD ObjectGUID. It uses this as a “primary key” on the set of MSOLIDs in the Directory. When it finds the correct MSOLID user, it can then check whether the mailbox or other resource that is being asked for, either has the correct permissions for the MSOLID or is owned by that MSOLID. Remember in the directory sync stage (Diagram 3), the AD ObjectGUID was one of the attributes copied.

- If everything checks out – the email is passed to the user.

All this redirection malarkey is part of the web-browser based protocol – WS-Federation. But you can see there needs to be a way for richer clients like Outlook or Office to perform similar actions. Rather than being “told” where to go by the app/federation server, these are “active clients” that can query the different services regarding where they should go and how they should authenticate. The main protocol that’s used for this is called WS-Trust. WS-Trust allows for the request and receipt of security tokens. But these richer clients also use WS-Metadata Exchange (WS-Mex) to discover the policy of the different services. Essentially the dance is very similar but the protocols are different. Also, the client can cache some long-lived token and then actively go out and request new ones or refresh the existing ones, rather similar to the way kerberos does it. But the question – will this all work with rich clients? Yes. Luckily when you set up Office 365 federation you run a few powershell scripts and it sets up the ADFS Server and all the necessary protocols and rules etc for you.

Note in this process that it’s still the MSOLID that owns or has permissions to the resources in Office 365. Nothing is assigned directly to the AD user. However, if the user forgets their password, it’s the AD helpdesk that sorts the problem out. The password policy is set by the AD administrator. The glue that links the on-premise AD environment to the in-cloud Office 365 environment is the AD ObjectGUID. You can now see why it is you can’t just authenticate with federation alone, you also need Directory sync because at its core, Office 365 uses MSOLIDs to determine access.

Is this blanket-SSO?

Yes – using Windows Azure Connect to domain-join you Azure Instances (and ensure you are deploying Windows Integrated Authentication applications to them!) alongside Office 365 with its attendant Directory Sync and Federation features will give you SSO across all the on-premise apps that implement Integrated Authentication and Office 365 services (through federated access). As mentioned above, Windows Azure Connect (formerly codenamed Project Sydney) is a virtual network that allows you to domain-join instances in the cloud. But you can also federate with Windows Azure based applications. When would you want to federate and when would you want to domain-join? Well, I’ve written a post to give some guidance on that.

If you’d like to understand a little more about federating your Azure apps to your AD, this post and this post will give you the architectural guidance you need.

Planky

Comments

Anonymous

November 30, 2010

Great article. Tanx. One question. I see you here talk about browser. Will this also work for MS Outlook?Anonymous

December 03, 2010

Yes - it works with a browser, with the rich Outlook client and with the Lync client. The client just has to support redirect with POST - browsers do it automatically but now that you can use Outlook over HTTPS (same with Lync), there is a basic browser-like functionality built in to these rich clients.Anonymous

December 07, 2010

This by far the best article I have read so far in terms of describing how MS will offer SSO to the cloud. Great Work!!Anonymous

January 27, 2011

This is awesome. One question: what happens if your local AD server is unavailable--e.g., your internet connection goes down? Does the Azure/Office 365 authentication server allow you in based on cached credentials? Or is everyone in your organization basically hosed and locked out of Microsoft's services until you get your internet connection back up and running again?Anonymous

May 11, 2011

One of the biggest problems we are trying to solve is that as we are developing a multi-tenant Azure application that enables organizations leverage identity federation with on-premise servers, there is also the need to cater to those buinesses that are "all in" or in other words completely in the cloud with solutions such as Office365 and without having any on-premise servers, where there is no possibility to federate with any on-premise Active Directory but still need single sign-on between Office365 and the Azure app(s). I know there is something referred to as "Microsoft Online ID" or "Office 365 ID" (not Windows Live ID; which does not help bridge the gap between Office365 and Azure) but there is no information available as to how or if it is possible to leverage that on Azure so that once signed in to Office365 and one opens up the URL for the Azure app, it should not prompt you to sign into that Azure app separately but simply take you to your post-login landing page, leveraging the Office365 credential's session state to enforce the user and group memberships/permissions for access control and permission in Azure. Schools looking to take advantage of Office365 are also trying to meld it with Azure they are either planning or looking into Azure apps and without being able to leverage MSOLID or Office365ID and Azure, it may be difficult to implement this, most especially when students, who usually are not AD federated need access to the Azure apps with the same Office365 credentials. If there is developer documentation on how bridge the gap between Office365 and Azure using MSOLID or Office365ID, I and tons of others will love to have it, perhaps post the link on this thread. This is getting requested more and more.Anonymous

June 01, 2011

This should be a T-Shirt " The miracle that is Kerberos"Anonymous

June 01, 2011

Yes - good one. I think the best T-Shirt I saw was issued by Oxford Computer Group. THey had the Los Angeles Police Department badge on it only instead of saying LAPD, it said LDAP. Great for directory services developers. Very much an in-joke...Anonymous

June 08, 2011

very useful info. Just had a couple of queries :

- If O365 uses MFG for its federation then why would it again do SAML (therefore establishing trust metadata etc) with the service O365 ? At that point wouldn't MFG act as a Proxy protecting services like O365 and doing federation for them ?

- I was wondering if (how) we can setup a federation relationship between Office 365 (as a Relying Party I guess, thru MFG) and a 3rd party Identity Provider for non-microsoft enterprise ? Does O365 always use Microsoft Federation gateway (hosted online) ? Where can I find all the URL endpoints to exchange ws-fed metadata and stup trust ? Thanks

Anonymous

February 19, 2014

I loved it. So easy to read and follow. Great learning source. Will definitely share this post with others.Anonymous

February 19, 2014

Hi Moiz, iam, Since this article was written the directory service that runs O365 is now known as "Windows Azure Active Directory". It's basically the same service but to help understanding, I have a video that describes it here: channel9.msdn.com/.../Windows-Azure-Active-Directory-Cartoon. The main point is that WAAD now has its own authN endpoint "built-in". The flow is basically the same but functionality has been extended to support more protocols. It now means you can use the same directory for both O365 and Azure/Internet-connected apps. The video above explains. I am aiming to get around to recording a more up-to-date version of what happens with O365 but time is a continual pressure.Anonymous

August 18, 2014

We have local ADs at our four office locations with same local domain names. Could you please guide us if we can link all these local ADs which have the same domain names to our office365. In addition, will the SSO work if the user is not connected to the office local LAN.