Create a web service for an app for Office using the ASP.NET Web API

You may have heard that apps for Office use client-side programming when communicating with the Office object-model. You may also have heard that apps for Office are especially well-suited for web mash-up scenarios, and are ideal for calling into web services and interacting with Web content. As a developer, how do you author your own web service? This post will lead you step-by-step through creating your own Web API service and calling into it from client-side app for Office code.

Sample code: All relevant code will be shown here. To download a copy of the sample code, see Apps for Office: Create a web service using the ASP.NET Web API.

Getting started

First, when would you need to author your own web service for an app for Office?

To do this |

Consider this… |

Establish a database connection, or connect to a service with a username and password. |

Encoding those in JavaScript is a serious security risk, as JavaScript code is trivially easy to inspect. Such calls should always be done on the server |

Perform any functionality where the algorithm/logic should be kept hidden from users |

Just as above, if your app encodes or transforms data (and if the algorithm for the transformation is something you need to keep secret), keeping the logic behind the server might be your only option. |

Retrieve external data that is not available in JSON-P format |

Browsers implement a same-origin policy that prevents scripts loaded from one domain to manipulate content in another domain. Data in JSON-P format can pass through, but other formats may not. Creating your own web service allows it to act as a “wrapper” around the external data, bypassing the browser same-origin policy limitations. |

Use existing server-side code or libraries (or to share a common back-end across multiple platforms) |

Suppose your app uses existing .NET Framework logic or libraries, or that you need to share a common back-end across multiple platforms. Exposing that functionality via a web service allows you to keep more of your existing code and libraries as is, without re-writing it to JavaScript. |

Perform licensing validation |

For apps posted to the Office Store, license checks must be performed via server-side code. |

Just to be clear, not all web-service scenarios require that you author your own web service. In particular, if your app consumes data from a public service that returns data in JSON-P format, you may not need to write your own web service at all. For purposes of this article, however, we’ll assume that there is some inherent business logic or data transformation that you need to expose to your app by means of writing your own web service. Let’s get started.

Using Web API

There are several possible choices for server-side technologies. For purposes of this article, I will be demonstrating the use of the ASP.NET Web API. Web API is an excellent framework for building REST applications, and Visual Studio provides first-class tooling support for it. The ability of Web API to communicate across a broad range of platforms makes it a particularly compelling choice for communicating between an app for Office and a corresponding web service.

Scenario

Let’s take a real-life example: You have an app, and now you want to add a “Send Feedback” page. To send the feedback, you’ll need to either log it to a database or maybe just email it to your development team – but in either case, you have sensitive data (connection string or a username/password combo) that you certainly wouldn’t want to expose via JavaScript. As we saw in the “Getting started” section, this is a canonical example of masking the back-end functionality behind a web service.

To make this example match real-world scenarios as closely as possible, let’s send multiple bits of information to the service: for example, an overall rating (an integer on a 1-5 scale) along with a string for the actual feedback. Likewise, the response we’ll get from the service will include both a Boolean status flag to indicate success, and a message back from the server (e.g., “Thank you for your feedback” or an error description). By framing the problem this way, you can see how this sample is analogous to more complex scenarios, like fetching data from a database via a web service (for example, sending a query with certain parameters, returning a data structure that represents the list of results, etc.)

Figure 1 shows a screenshot of the app we’re aiming to build. Again, to download the full sample project, see Apps for Office: Create a web service using the ASP.NET Web API .

Figure 1. Screenshot of the “Send Feedback” sample app.

Create the app project

To get the example up and running quickly, let’s just create a new task pane app for Office project, and place the “send feedback” functionality as part of the home screen. Of course, if you have an existing project where you’d like to append this functionality, you could create a SendFeedback folder, add two files called SendFeedback.html and SendFeedback.js within it, and place the functionality there, instead.

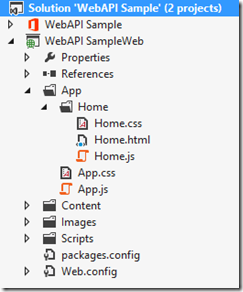

This example assumes you’re using the latest version of Office Developer Tools. Thus, when you create a new project, you should get a project structure as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Visual Studio project structure.

Open Home.html, and replace its <div id=”content-main”> section with the following code.

<div id="content-main">

<div class="padding">

<p>This sample app demonstrates how an app for Office can

communicate with a Web API service.</p>

<hr />

<label>Overall rating: </label>

<select id="rating" class="disable-while-sending"

style="width: inherit">

<option value=""></option>

<option value="5">★★★★★</option>

<option value="4">★★★★</option>

<option value="3">★★★</option>

<option value="2">★★</option>

<option value="1">★</option>

</select>

<br />

<br />

<label>Feedback:</label>

<br />

<textarea id="feedback" class="disable-while-sending"

style="width: 100%; height: 200px"

placeholder="What would you like to tell us?"></textarea>

<button id="send" class="disable-while-sending">Send it!</button>

</div>

</div>

As you can see, the HTML is very standard, containing a dropdown for the star rating (★ is the Unicode symbol for a star), a textarea for the textual feedback, and a button to send the data. Note that each of those components carries a unique ID, so that it can be easily referenced it via code. I also am applying a class called “disable-while-sending” to each of those three elements – again, just as a way to reference these elements from code – to be able to provide a status indication after the user has clicked “send”. Remember that web service calls are done asynchonrously, so disabling the controls provides both a visual indication, and prevents users from clicking “Send” multiple times while the first call is still underway.

Let’s add a corresponding JavaScript file as well, with a placeholder for the sending procedure. If you’re following along with Home.js, replace the entire contents of that file with the following code.

/// <reference path="../App.js" />

(function () {

"use strict";

// The initialize function must be run each time a new page is loaded

Office.initialize = function (reason) {

$(document).ready(function () {

app.initialize();

$('#send').click(sendFeedback);

});

};

function sendFeedback() {

$('.disable-while-sending').prop('disabled', true);

// Magic happens

}

})();

Okay, that’s as far as we can get for now. Let’s add our web service.

Adding a Web API controller

With Web API, anytime you call a method on a server, you’re doing so via a Controller. So, let’s add a Controller to handle our SendFeedback action.

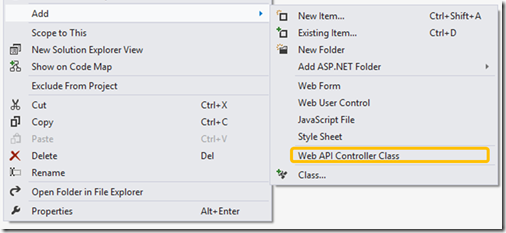

You can add a controller anywhere within your web project. By convention, however, controllers go into a “Controllers” folder at the root of the project, so let’s go ahead and create it now.

After you create the folder, if you choose it and mouse over the “Add” menu, and you should see the option to add a Web API Controller class. The same option should be available under the “Add” > “New Item…” dialog, as well. Let’s add the Web API controller class now.

Figure 3. Adding a Web API Controller Class.

By another convention, that is somewhat more strictly enforced, Web API controllers must end with the suffix “Controller” in order to be properly recognized by the routing mechanism. This isn’t to say you can’t change it, but that does require a bit of extra legwork. So for now, let’s appease the Web API plumbing architecture, and name our controller “SendFeedbackController”.

We can leave the auto-generated code be for the present, and move onto the next step. We’ll be returning here in a moment.

Setting up the Web API routing

There is a quick side-step we need to take in order for our Web API Controller to function: we need to register it with the web application. Some flavors of web projects, like MVC, include support for Web API routing by default. The default app for Office does not include this plumbing, but it’s not hard to add.

Note that this step is best done after you’ve already added a Controller to the project; otherwise, you need to set up some references manually. This is why this post has you first add the controller, and only then register it.

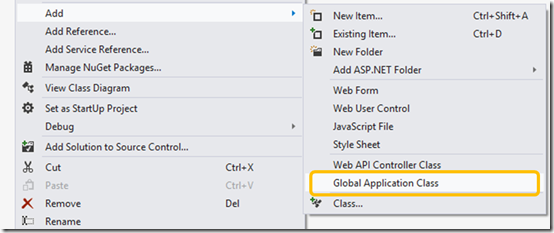

To add the Web API routing registration, right-click on the root your web project, select “Add”, and you should see “Global Application Class” as one of the options. It should also be available under the “Add” > “New Item…” dialog box. The default name of “Global.asax” should suffice.

Figure 4. Adding a Global Application class.

Once you’ve added Global.asax, the file should automatically open, with empty method stubs filled out. Add the following two “using” statements somewhere at the top of the file.

using System.Web.Routing;

using System.Web.Http;

The only method you need to touch is the Application_Start method. Add the following code into the Application_Start body (the rest of the methods can remain empty).

RouteTable.Routes.MapHttpRoute(

name: "DefaultApi",

routeTemplate: "api/{controller}/{id}",

defaults: new { id = RouteParameter.Optional }

);

What does this means? In a nutshell, the method registers your controllers to be available under the “api” route, followed by the name of the controller and an optional ID (in case of parameterized queries). The {ID} will not be used for our final SendFeedback controller, but it doesn’t hurt. Note that you can also specify other parameters under routeTemplate, such as “{action}”, to include the name of the action as part of the URL. Refer to "Routing in ASP.NET Web API" for more information on configuring Web API routing, if you’re curious.

Filling out the Controller

The SendFeedbackController class has some auto-generated code that demonstrates some of the capabilities of Web API, including responding to various HTTP verbs (“GET” vs. “POST”, and so on), routing based on the ID parameter, and so forth. While these capacities are certainly worth exploring on your own (e.g., for an example of how to return a list of values), they are not necessary for our current “Send Feedback” scenario. For our purposes, all we want is a single method that takes in some data (overall rating and feedback text), and returns some data (a status and a message).

Data structures

Let’s write some data structures to hold the request and response objects. You can write them as inner classes within SendFeedbackController.

public class FeedbackRequest

{

public int? Rating { get; set; }

public string Feedback { get; set; }

}

public class FeedbackResponse

{

public string Status { get; set; }

public string Message { get; set; }

}

Nothing fancy – we’re using built-in data types (strings, integers) to build up the more complex request and response classes. If you’re curious why Rating is a nullable (int?) type, this is both to demonstrate that you can do this, and to handle the case where the user does not fill out a rating in the dropdown.

Method signature

Now let’s create the actual SendFeedback method. Go ahead and delete the other method stubs (they’re only there as examples, and you can always re-generate them by creating a new Web API Controller). In their place, let’s put a single SendFeedback method, which takes in a FeedbackRequest, and returns a FeedbackResponse.

[HttpPost()]

public FeedbackResponse SendFeedback(FeedbackRequest request)

{

// Magic happens

}

We will be using the HTML “Post” verb to post data to the controller. (For a discussion of POST versus GET, search the web for “when to use POST versus GET”). Note that you can either put the word “Post” as part of the method name, or you can name the method what you’d like, and annotate it with a “[HttpPost()]” attribute. It’s a matter of personal preference.

Try-catch

Let’s wrap our method body in a try-catch block, so we can gracefully handle any errors that occur as part of the method. The “catch” is shorter, so let’s fill that out first.

try

{

// Magic moved to here

}

catch (Exception)

{

// Could add some logging functionality here.

return new FeedbackResponse()

{

Status = "Sorry, your feedback could not be sent",

Message = "You may try emailing it directly to the support team."

};

}

What’s happening here? Because the controller’s method is the very outer layer of the API, we want to ensure that any exceptions are caught and handled appropriately. Thus, on failing, we will still send a response via the data structure we defined, with an appropriate status text and message. Note that as part of the “catch”, we could instead throw a new HttpResponseException rather than returning a FeedbackResponse, and handle the exception on the client – it’s a matter of preference / convenience. However, performing a try-catch on the server-side code is still be useful for logging or for a potential fallback mechanism. For a more thorough discussion of Web API error handling, see “ASP.NET Web API Exception Handling” on the ASP.NET Blog.

The mail-sending functionality

Now let’s tackle the body of the “try”. First, if we’re going to send feedback via email, we’ll probably need to gather up some credentials.

const string MailingAddressFrom = app_name@contoso.com;

const string MailingAddressTo = "dev_team@contoso.com";

const string SmtpHost = "smtp.contoso.com";

const int SmtpPort = 587;

const bool SmtpEnableSsl = true;

const string SmtpCredentialsUsername = "username";

const string SmtpCredentialsPassword = "password";

For the subject, let’s use the name of the app and the current date, so that it’s easy to distinguish individual feedback items.

var subject = "Sample App feedback, "

+ DateTime.Now.ToString("MMM dd, yyyy, hh:mm tt");

For the body, we will append the rating and the feedback. Notice how we’re using the request object to read these values, just like we would with any normal function parameters.

var body = "Rating: "

+ request.Rating + "\n\n" + "Feedback:\n"

+ request.Feedback;

Now we create the mail message and send it via the SmtpClient class (note that you’ll need to add a “using System.Net.Mail;” statement to the top of the file).

MailMessage mail =

new MailMessage(MailingAddressFrom, MailingAddressTo, subject, body);

// Send as plain text, to avoid needing to escape special characters, etc.

mail.IsBodyHtml = false;

var smtp =

new SmtpClient(SmtpHost, SmtpPort) { EnableSsl = SmtpEnableSsl,

Credentials =

new NetworkCredential(SmtpCredentialsUsername,

SmtpCredentialsPassword) };

smtp.Send(mail);

Because we’re using a try-catch block, we know that if the code has reached past the Send command, the feedback was sent successfully. So we can return a FeedbackResponse object back to the user.

// If still here, the feedback was sent successfully.

return new FeedbackResponse()

{

Status = "Thank you for your feedback!",

Message = "Your feedback has been sent successfully."

};

Our controller is now done! Now we just need the client-side piece.

Back to JavaScript

Let’s return to our sendFeedback() method stub that we left in the JavaScript code in Home.js. We’re just about ready to finish the app.

First, we want to disable the “send” button and the other fields while sending is underway.

$('.disable-while-sending').prop('disabled', true);

Next, prepare the data to send. Note that we create a JavaScript object to hold this data, but with property names (“Feedback” and “Rating”) matching the names of the FeedbackRequest fields from our .NET Controller.

var dataToPassToService = {

Feedback: $('#feedback').val(),

Rating: $('#rating').val()

};

Finally, we make a jQuery AJAX call. The URL is relative to the page form which we’re calling the request, hence we go back two levels (to escape “App/Home/”) before turning to “api/SendFeedback”. The data type is “POST”, which matches what the controller expects. For the data, we stringify the above “dataToPassToService” object, and add the appropriate content type. (Tip: While it’s not necessary for POST request, you may want to specify an explicit “cache:true” or “cache:false” for GET requests, depending on whether or not those should be cached).

$.ajax({

url: '../../api/SendFeedback',

type: 'POST',

data: JSON.stringify(dataToPassToService),

contentType: 'application/json;charset=utf-8'

}).done(function (data) {

// placeholder

}).fail(function (status) {

// placeholder

}).always(function () {

// placeholder

});

Now onto the final stretch of filling out the placeholders above. If the AJAX call succeeds, we’ll display a message to the user, using the Status and Message fields that we get from the controller’s FeedbackResponse object. Let’s substitute that into the “done” placeholder above.

app.showNotification(data.Status, data.Message);

If the call fails (for example, you are offline), let’s add a similar notification (“fail” placeholder).

app.showNotification('Error', 'Could not communicate with the server.');

Finally, regardless of whether the call succeeded or failed, let’s re-enable the controls so that the user can try again, or send another bit of feedback, or copy-paste the feedback and send it via email. Thus, for the “always” placeholder, let’s do.

$('.disable-while-sending').prop('disabled', false);

Our code is now officially complete.

Run it!

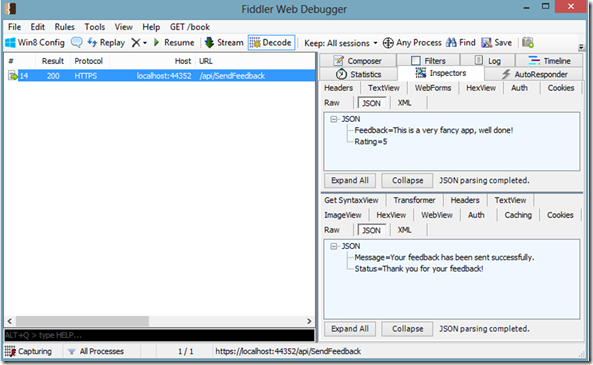

Let’s have a celebratory run. Press F5 to launch the project, and add some feedback text and a rating in the appropriate fields. Press “Send”. If all is well – and if you have substituted the Controller’s email account constants with appropriate credentials – you should see a notification in the UI that your feedback has been sent, and you should also receive an email with a copy of the feedback. If you’re curious about what is happening behind the covers, you can use a tool like Fiddler to analyze the serialization “magic” that’s happening behind the covers. You can also use Visual Studio to pause on breakpoints, both in the JavaScript code and in the Controller.

Figure 5. Fiddler trace showing data passing in and out of the web service

The example in this post is just the tip of the iceberg: I am excited to see what apps folks will build, leveraging the flexibility and responsiveness of client-side code, and the power and security of server-side code. Please leave a comment below if you have any questions or comments.

~ Michael Zlatkovsky | Program Manager, Visual Studio Tools for Office & Apps for Office

Comments

- Anonymous

October 23, 2013

Very nicely written. One of the msdn folks pointed me to this sample. I had seen the sample in the pack but the blog clarifies many subtle aspects. I am currently trying to do a similar async call to a WCF Web service. I created a VS 2012 Office App. I copied simple "int Add(left, right) ..." code from the sample app code.msdn.microsoft.com/.../How-to-consume-WCF-service-48b43a79 which has a different directory structure from mine and it also seems to use http: instead of the default https: (produced by VS 2012 Office App template). The sample app's WcfService has url relative to root of application: $.ajax({ type: 'post', url: '/WCFService.svc/Add', ... For my OfficeApp I have tried "/WCFService/Add" and url '../../WCFService.svc/Add' relative to the Home.html page In both cases I get Not found. I am wondering if the problem is due to https being the default in VS 2012 unlike in the sample app. I do not see any obvious place where I can change this in my Office App project in VS. If I start with sample app code (and not VS 2012 template dir structure), I can add new methods etc to my WCFService and everything is working well. I would like to stick to the Office App std and I cannot figure out what is the problem.

- Jayawanth

Anonymous

December 28, 2013

Hi Michael, Thank you for the article. Too bad that after the admonition to use JSON-P you don't show a GET operation that uses this format. I am using Web API as well and I'm afraid it's returning JSON rather than JSON-P, which then causes my JQuery $.getJSON call (which calls your $.ajax call) to fail with a JavaScript runtime error "Access is denied". When I use Fiddler it shows me JSON data being returned. I don't know if Fiddler knows the difference between the two. -Tom.Anonymous

January 09, 2014

@Jayawanth: I would recommend that you debug via a browser and Fiddler. E.g., create a regular web page that does not reference Office.js, run it in a browser, and then try to see if you can call the WCF service there. You can try with both the HTTP and HTTPS endpoints, though it really shouldn’t be making a difference. Once you get it working in a browser or see how it fails in the browser and inspect the Fiddler log, it may shed insights into how to fix it for the app for Office case. Hope this helps!

- Michael

- Anonymous

January 09, 2014

@Tom: To be clear, JSON is perfectly fine to use between your web server and your app, provided they’re on the same domain. The restriction for not passing JSON across domains is not Office-specific. See this, from JQuery’s website (api.jquery.com/jQuery.getJSON): "Due to browser security restrictions, most "Ajax" requests are subject to the same origin policy; the request can not successfully retrieve data from a different domain, subdomain, or protocol." Web servers, on the other hand, can fetch JSON from wherever they want. This means that your web server (C# code) can fetch JSON on your app’s behalf, and then pass it on to your website – avoiding the same-origin issue that you would have otherwise, if the original source is not JSON-P. So I would guess that the “Access is denied” issue is something else. As in my reply to Jayawanth, I would attempt to try to debug in the browser, to see what might be the root cause. Best of luck,

- Michael

Anonymous

May 16, 2014

Great post! When I build the example ReSharper complains that the 'disable-while-sending' CSS class isn't defined. However when I run the project the controls are disabled. Just curious where it is?Anonymous

May 16, 2014

Hi John, Good question :-) ReSharper is sort of correct -- the class is, in fact, not defined in any CSS. It is only used as a placeholder in the HTML so that JavaScript can grab it and enable/disable the elements as needed -- but it actually carries no stylistic effect. There could be other ways to do it (and you could appease ReSharper simply by defining an empty style), but for purposes of this article I wanted to keep things as bare-basic as possible, without the need to create a separate CSS file (hence some of the inline-d styling in the HTML, which would have been in a CSS file otherwise). Makes sense?

- Michael

Anonymous

May 18, 2014

Ok so it is not a CSS style but rather JavaScript disables that element labeled with that class because we set its property 'Disabled' as true in the function. That makes sense. Thanks!Anonymous

June 22, 2014

Hi Michael, It would be really helpful to others who start to develop office app. Great Initiative to build this sample.Anonymous

June 22, 2014

Hi Michael, Can i use class library without webservice or web api in office app?Anonymous

June 23, 2014

Hi Keyur, You can certainly include a class library or general C#/VB code in your project, and then use server-side rendering (e.g., asp.net pages or MVC) to render content that invokes the servers-side code as well. But the use of HTML/JS/CSS + a web service makes the application more lightweight and "modern".

- Michael

Anonymous

June 24, 2014

Thanks Michael, We are designing our office app for excel. We have add-ins for excel, now we are developing office app for the same add-ins. We are thinking to take as much as reusable code in our Office app. Our lots of code in class library. I am confuse in designing office app. What should i use ? MVC or HTML? Is there a sample app for using MVC5 with apps for office ? Is there any deployment issue with above scenario. ?Anonymous

July 08, 2014

Hi Keyur, Depending on what your add-in does, you might be able to keep the code that does most of your processing as C#/VB server-side code, and have the app for Office just be a messenger that extracts data from the document, sends it to your Web API service and the class libraries you have today, retrieves the data back via AJAX, and then writes it back to the document using the functionality in Office.js Whether you use HTML + WebAPI or something like MVC is up to you. MVC is (among other things) a tempting engine when you want to create multiple pages that share the same look. Since Office apps interact with Office via client-side code (Office.js), having multiple pages doesn’t make as much sense – keeping the app as a single page (or just a few pages) will likely provide a better user experience, and a better way to keep track of the state. As such, just keeping the app in HTML/JS/CSS and using Web API as the server-code endpoint is probably what I personally would do. But individual scenarios differ… For what it’s worth, I had a discussion with a customer in the past about converting his add-in to an app for Office. If you’re curious, read through the thread on blogs.msdn.com/.../create-a-web-service-for-an-app-for-office-using-the-asp-net-web-api.aspx. Scroll halfway through the thread to get to the relevant part. Hope this helps,

- Michael

Anonymous

September 03, 2014

Thanks Michael for reply my post. I have another question for Office App :-). I have a my Office App in Excel and i want to use my office app on web only. Our users doesn't have Office installed in their computer(PC). Users has Office 365 license subscription. Can users use Office app on Web only without installed office in machine?Anonymous

September 05, 2014

I am not sure if you can insert an app for Office from the Web client -- but if you have a document that already has an app for Office in it, yes, that should work for Excel and PowerPoint.Anonymous

December 05, 2014

Hi, Can i use Office 365 Sharepoint Lists and add/update their item in access web app ? If yes then what we need to do into our web service?Anonymous

February 16, 2015

I try to use the sample in a Mail App, but I always get the message 'Could not communicate with the server.'Anonymous

July 15, 2015

Very nicely explained. I tried to implement but I get the error defined in AJAX fail case. I looked at Console of browser and saw that the cause was error '404'. I tried to change the URL in AJAX call but no luck. Please help. I've provided the link for screenshots of my console and VS project directory structure. Console: pasteboard.co/1ZWJhzaO.png VS: pasteboard.co/1ZWKwF5S.png