Live migration on GPU-P devices

This article describes the functional design of the live migration of heterogeneous compute devices (GPUs, NPUs, etc.) virtualized through SR-IOV (single root I/O virtualization) partitioning. Devices that support partitioning through the WDDM and MCDM driver models are now an integral part of our virtualization offerings. Thus, it's important to support live migration and help our virtualization abstractions become maximally reliable to the impact on customers when resource assignments must change. This article also describes the quick migration of these devices as well.

Live migration is supported starting in Windows 11, version 24H2 (WDDM 3.2). It's more generally an extension of the GPU paravirtualization (GPU-P) DDIs for drivers that expose the capability. MCDM drivers that implement the GPU-P virtualization interfaces can optionally also implement these live migration interfaces, including their extension with triage events.

In this article, "GPU" simply refers to devices that implement the GPU-P virtualization framework, whether WDDM or MCDM, and whether a GPU, NPU, or other heterogeneous compute device.

Kinds and Purpose of Resource Migration

Resource migration is the ability to move a virtualization to new physical resources. There are various ways in which virtualized execution can be moved, including:

Hard power down. The virtual motherboard can be powered down directly, stopping execution of the virtual resources. Any applications that aren't powerhit-tolerant lose the data they're operating on, and all device state is wiped. The virtual hard disk (VHD) can then be virtualized on a different host machine, which results in a cold boot.

Soft power down. This power down differs from the hard power down in that it simply sends the power request to the guest OS. The guest OS then distributes the power-down mechanism to applications to cleanly shut down. Applications can use this notification to safely store all data and register to restart on boot, though it's dependent on each application’s programming. A soft power down requires a guest OS that supports this mechanism of clean shutdown and the appropriate services to store current state and restart on reboot.

Hibernation. This other guest-originated technology allows the guest to transition to a fast-starting sleep power state where all application processes are frozen, the device state is purged to CPU memory, and all memory is then sent to storage to allow the hardware to power down. Then, the VM storage VHD can be restarted on a different machine, and the memory loaded, the device state restored, and the processes unfrozen. Hibernation is only available on guest OSes that support it. It's a fairly invasive process that depends on guest stability, but it provides a mechanism to restore application processes with state that the power down mechanisms don't provide.

Quick Migration (also known as VM Save and Restore). With this technology, the VM is paused (vCPUs stop scheduling) and all state needed to restore state on the new physical resources is gathered inside the Host OS – including the memory of the VM and the state of all devices. This state is then transferred to the new Host that creates a VM with all vCPU contexts loaded, maps the memory to the VM space, and restores the device states. A PowerOnRestore then restarts execution of the vCPUs. This technology is independent of the Guest OS and doesn't depend on execution in the guest environment, so it's a more reliable way to maintain process and device state than Hibernation. The virtualization user might notice a significant down time as the VM memory can be many GBs and transfer times can be noticeable.

Live Migration. If we have the ability to transfer content while the virtualized resources are still active and we can track content that gets dirtied, we can transfer significant content while leaving the virtualization active. Then, when the VM is paused, far less content needs to be transferred and we can minimize the time the virtualization isn't executing. The result is minimized end-user impact, as all operations occurring during the migration continue unimpeded and the impact to resource consumption rate is reduced as far as is currently possible. In particular, outage deadlines (external time constraints to the virtualization outage, like TCP and other protocol timeouts with external endpoints) can be minimized or eliminated.

Each progression reduces or removes some (often major) customer awareness of the change in physical assignment of a virtualization, making the virtualization more and more complete and transparent to the user. Along with other technologies (like Host crash isolation) that separate out the customer dependencies on infrastructure, it moves our virtualization solution towards the ideal of assignment independence and true ephemeral compute.

Large-Scale Design

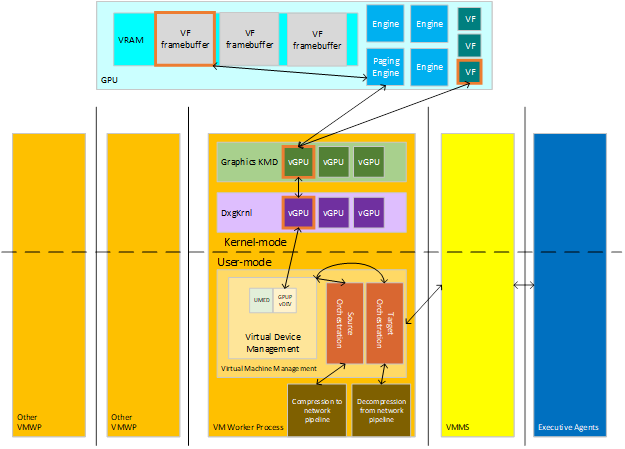

Live migration transfers virtualization content from a Source Host to a Target Host. The virtualization consists of various stateful devices, which can include memory, compute, and storage, each with data that must be transferred from the devices on the source over to the devices on the target. Executive Agents that manage virtualizations across clusters communicate to Hosts to let them know to set up orchestration for either Source Migration of an existing VM (when the content is leaving the Host) or for Target Migration to a new VM (to receive the content). The major players in this interaction are seen in the following diagram.

:

Epochs of the Source Host

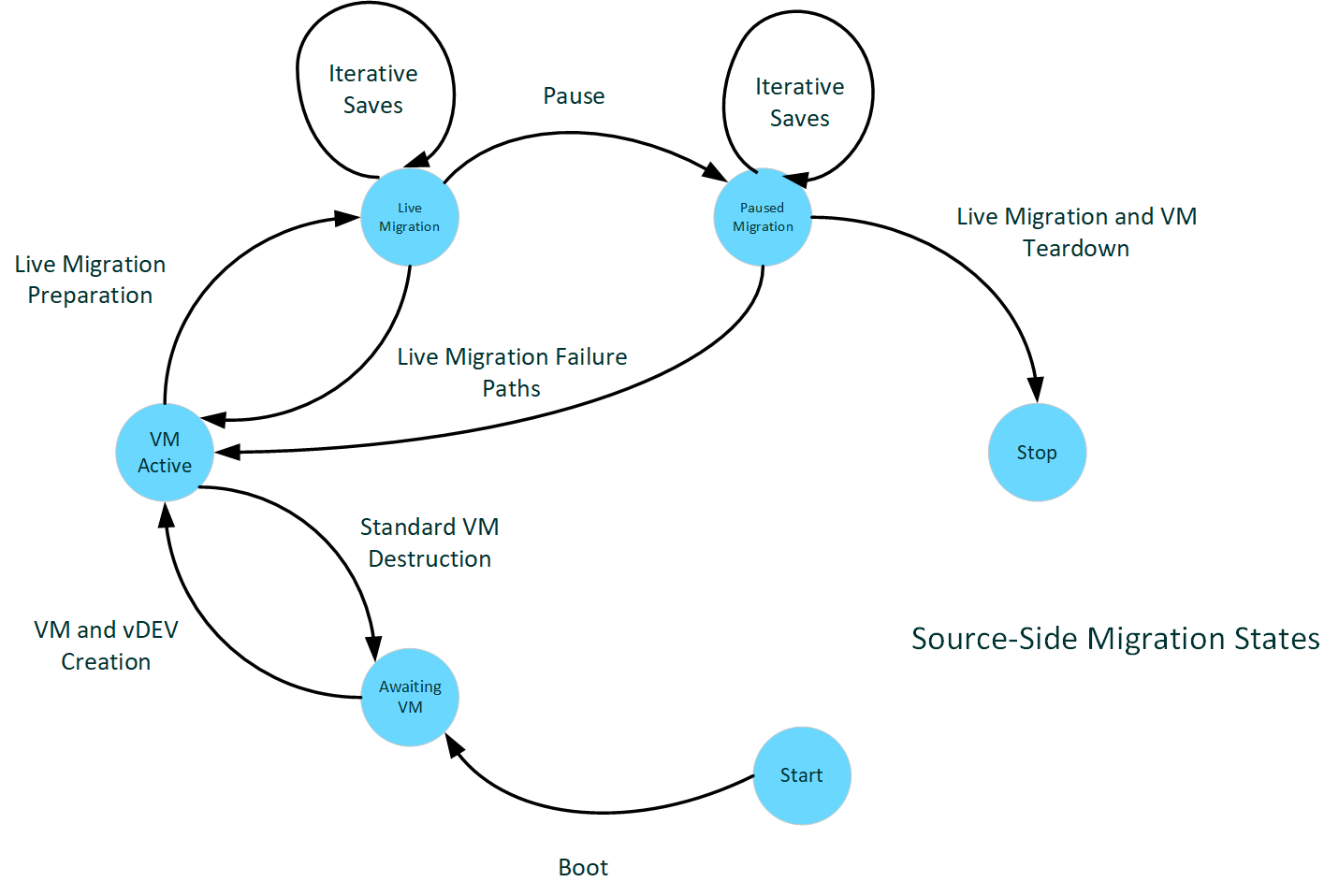

The following diagram illustrates source-side migration states.

:

Source-side boot

When a Host boots generally, the KMD reports device capabilities to the kernel through various initialization calls.

When the KMD receives the DxgkDdiQueryAdapterInfo call for DXGKQAITYPE_GPUPCAPS data, it can set the LiveMigration capability bit added to DXGK_GPUPCAPS. When KMD sets this bit, it indicates that the driver supports live migration.

A prerequisite to live migration support is to support for the tracking of modified VRAM pages on all GPU-local memory segments, as described in Dirty bit tracking. That support is reported through other DxgkDdiQueryAdapterInfo calls for other specified information types. A driver that reports support for live migration must also report support for dirty bit tracking. Support for live migration but not dirty bit tracking is an invalid configuration and Dxgkrnl fails to start the adapter.

VMs online

Once the host boots and the management stacks are online, virtual machine activity begins to come online. Requests for starting and stopping VMs begin to arrive and we start to see GPU-P vGPUs projected into these virtualizations.

Assuming performant dirty bit plane capability, Dxgkrnl calls DxgkDdiStartDirtyTracking after reserving the VRAM resources for a VF (virtual function), which allows the system to track VRAM cleanliness in the case where the VF later participates in a migration scenario.

This VM startup begins to intercept interrupt table access to virtualize interrupt support, which proceeds for the lifetime of the VM.

Live migration send preparation

The management stack sends the event to begin live migration when indicated by its controls, and the migration state machine management gathers all state from the virtual device that's immutable for the lifetime of the virtualization (vGPU partition configuration metrics) in order to reconstruct the vGPU on the target. Once ready, the process of preparation of the transport buffers and initialization of the transport stack is started.

This epoch generates a call to the introduced DxgkDdiPrepareLiveMigration DDI. KMD should establish the PF/VF scheduling policies that provide for the live migration’s ability to stream dirty content from the VRAM in the host while preserving fair performance for the VF. If the dirty tracking is reported as nonperformant, this point is also where dirty tracking is started.

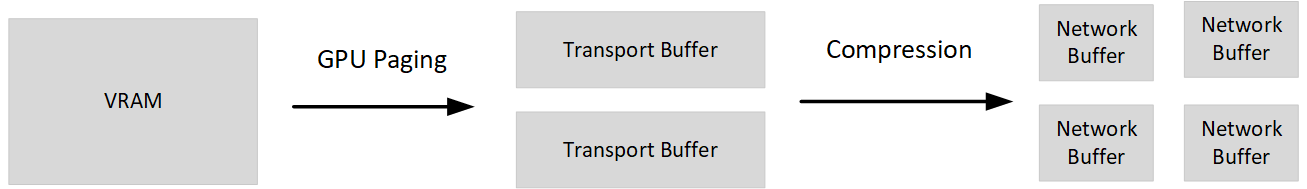

Live migration send

:

We then enter the active phase of the dirty VRAM transfer. This phase involves making calls through the dirty bitplane DDI to get snapshots of the VF framebuffer and then paging those pages from the GPU to the CPU buffers prepared earlier.

There comes a stage in this transfer where the VM and all its virtual devices are paused. The VF can stop being scheduled for the guest, and at this time, any extra timeslice that can be given to the PF to finish the paging of content should be. Because both the VF and the vCPU are paused in the VM, there should be no further changes to content being migrated (CPU or device-local memory) after this point.

Paused migration send

The last iterations of dirty pages are transferred while paused. At this point, a call is made to gather any last pieces of device and driver state that was mutable while active and couldn’t be transferred in the earlier preparation. This state can be any state reconstruction needed on the other side, any tracking structures, or generally all information necessary to finalize the restoration of VF state on the target side.

Live migration teardown

Finally, once the VM and all of its virtual devices have transferred their state to their new physical realizations, the source side can clean up the VM remnants. The buffers and other migration state are cleared up and the vGPU is destroyed.

Epochs of the target host

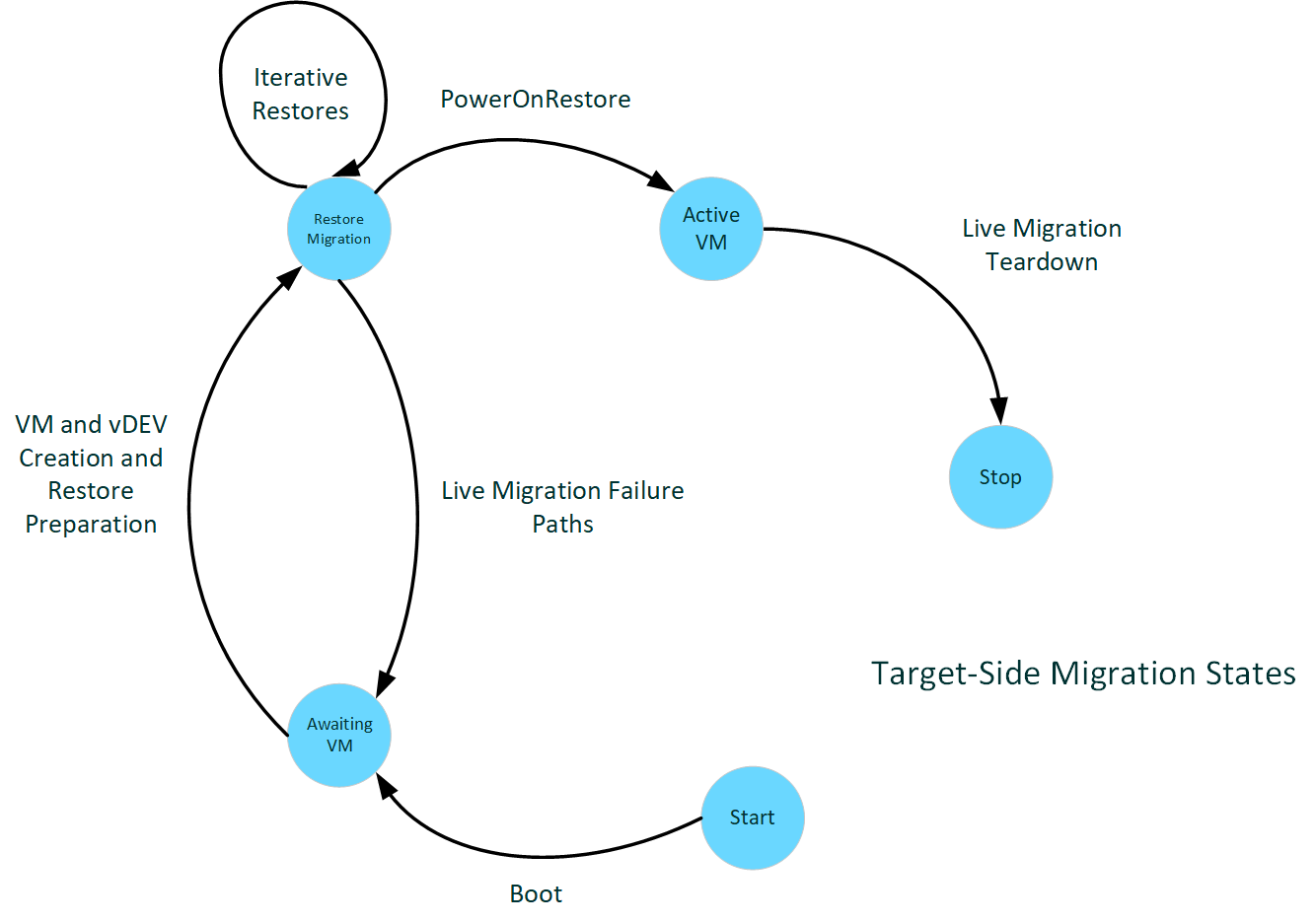

The following diagram illustrates target-side migration states.

:

Target-side boot

Boot on the target looks the same as on the source. Boot is for the whole system, which can be a source and target on different VFs throughout its lifecycle. The driver just needs to specify support of live migration to participate.

Live migration receive preparation

On the target side, the VM is constructed starting as if it were a new VM. The VM and the virtual devices are created. This creation process includes the virtual GPU, created using the same parameters it was created with on the source side. After creation, the validation data is received and passed to the driver to validate that the target side is compatible with the source to restore the VM. At that point, it should ensure anything that could affect such compatibility, including driver version, firmware version(s), and other ambient state of the target system and driver. The driver will configure to allow the PF access to all timeslice of paging that would normally be assigned to the VF while that VF isn't yet active.

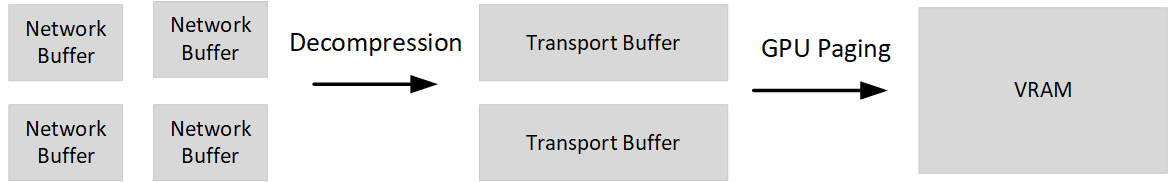

Live migration receive

:

Receiving dirty page data is similar to the stage on the source except the paging direction is from CPU buffers to VRAM. All transfers are made while the VF is paused, so the entire transfer can be done within the VF budget.

VM start and teardown

Once all of the VRAM migration is complete, the vGPU gets a chance to set up any additional state that needed to be transferred (the final mutable save data). Then we start the VM on the target and teardown the migration state, including the buffers used for the transfer.

Performance Goals

An important part of live migration is its responsiveness. In particular, it minimizes the downtime of the virtualization where it doesn't respond externally (either to the user of the virtualization or any endpoints it might be further connected to). Many network stack protocols have timeouts across remote machines that are quite brief before retry/reestablish fails, and so can be disruptive to the user when dropped. As a common fixed goal, the total pause time to transfer and start should be under three quarters of a second (750 ms), which pushes the time out of contact to under many of the most common stack timeouts.

Additionally, the performance changes to the active system shouldn't trigger other end-user disruptions if at all possible. In the devices using these DDIs, the system shouldn't significantly increase the rate of TDRs by slowing down the timeslice scheduled. Now, we expect most TDRs aren't long packets but hung devices instead, and doubling or tripling the time to execute a packet shouldn't push most packets over the large timeouts of seconds. But we need to be aware of not triggering our timeouts in the general performance picture.

Device driver interfaces

Generally, the live migration DDIs refer to the general concepts of WDDM and MCDM DDIs and the GPU-P virtualization DDIs in particular.

hAdapter generally refers to the handle token that represents a specific device that this driver manages. Systems with multiple physical devices enumerated by the system might have a driver manage multiple hAdapters, so hAdapter localizes to the specific device.

vfIndex identifies which virtual function / vDEV is being referenced. It localizes to the specific virtual device. It's sometimes also called the partition ID.

DeviceLuid also localizes the specific virtual device, but down in the language of the UMED interface with the virtual device management.

SegmentId identifies specific VidMm segment exposure when referencing content stored on the device, like VRAM reserve.

Note on interface definitions

This article refers to dynamically sized structures. These structures are implemented through dynamically sized arrays, which the reference pages describe like:

size_t ArraySize;

ElementType Array[ArraySize];

where the interface passes an array size earlier in the structure and the parsing of the interface object then iterates over that many elements when the array is supplied. These declarations aren't valid C/C++ as those languages express statically sized fragments. Read in the static-sized structure first and then dynamically parse in code.

Device start and caps reporting

The following capabilities are added to DXGK_GPUPCAPS:

- The LiveMigration cap indicates driver support for the live migration feature (generally, the added DDIs mentioned in this article except for DxgkDdiSetVirtualGpuResources2).

- The ScatterMapReserve cap indicates driver support for DxgkDdiSetVirtualGpuResources2, which will be added in a future release.

KMD must fill out these caps when the OS calls DxgkDdiQueryAdapterInfo with a DXGKQAITYPE_GPUPCAPS request. The OS queries caps during device initialization after DxgkDdiStartDevice is called and when the adapter supports GPU partitioning.

If the driver returns the ScatterMapReserve cap, it needs to expose the added DXGKQAITYPE_SCATTER_RESERVE type with the following associated structures so that the OS can query the driver's scatter reserve capabilities:

- DXGK_QUERYSCATTERRESERVEIN for pInputData

- DXGK_QUERYSCATTERRESERVEOUT for pOutputData

Scatter-paging support

In order to support the transfer of noncontiguous dirty pages to and from the framebuffer, this feature is one of the first to exercise GPU-VA mappings that aren't backed by contiguous physical addresses. The current paging interfaces don't need to be updated for this support as it's always been a general possibility supported by the page tables. But any latent implementation details that made assumptions about contiguity are likely exposed by this change. So it's important to understand this OS mechanism, how it executes the virtual paging interfaces, and ensure that the paging is robust to this change.

In particular, the TransferVirtual interface now passes VA ranges that aren't mapped contiguously on the framebuffer.

Live migration start send-side

When the system starts the live component of the migration, it needs to call the added DxgkDdiPrepareLiveMigration DDI. This call notifies the driver that this epoch has started and allows it to configure the VF scheduling policy for the migration, which should apportion some of the free and migrating-VF budget for PF paging.

Dxgkrnl then calls KMD's DxgkDdiSaveImmutableMigrationData DDI to gather information about the device to restore on the target side.

After the system gathers and sends the immutable data and validation data, the main iterative loop of dirty send begins.

Iterative save/send

As described in the overview section, the iterated save operation uses DxgkDdiQueryDirtyBitData to snapshot the current dirty bitplane for the VF at the start of each iteration and uses the standard DXGK_OPERATION_VIRTUAL_TRANSFER operation to page the reported dirty pages. If this operation occurs on a device that reported in its dirty tracking capabilities that it isn't a negligible performance impact, the system's iteration control first enables dirty tracking and then transfers the entire framebuffer before the first call to query the dirty bitplane.

For the virtual transfer, the primary updated behavior is that the mapping isn't contiguous VA to contiguous PA. Instead, there might be disconnected pages of PA under the mapping. Otherwise, the behavior is as described in the original paging and dirty bitplane tracking documentation, and this feature doesn't add to that.

Live migration end send-side

At the end of the migration, the system needs to collect all device and driver state needed to finish rebuilding state and tracking that hasn't yet transferred. This data couldn't be transferred because it didn't fit the immutability requirements of the earlier migration data and wasn't VRAM dirty content. Dxgkrnl calls the added DxgkDdiSaveMutableMigrationData DDI to do so. This DDI's usage is similar to DxgkDdiSaveImmutableMigrationData.

Eventually, when there's no more need for migration configuration on this VF, DxgkDdiEndLiveMigration is called. All scheduling and state should return to a nonmigrating configuration.

Live migration start receive-side

When the immutable data comes in on the receiving side, the system passes it directly to KMD through a call to DxgkDdiRestoreImmutableMigrationData.

This DDI should only ever be called for VFs that are currently paused.

Iterative restore/receive

Again, the scatter paging operates in an iterative manner, but this time without the calls to inspect the dirty bitplane associated to the framebuffer reserved by the VF, because the dirty bitplane on the target is constructed by the paging. The direction of paging is reversed. Content in the received buffers is transferred to the VRAM, with the placement of the pages dictated.

Live migration end receive-side

Once the migration is coming to an end, the receiving-side system calls the driver's DxgkDdiRestoreMutableMigrationData function with the final package of state to restore. This package should provide all the content that was left for the driver to transfer over for restoration of its state and tracking, and for the remaining restoration of the VF state.

This DDI should only ever be called for VFs that are currently paused.

After this call, the system calls KMD's DxgkDdiEndLiveMigration function to let the target side know to clean up any state around the live migration, including restoration of normal VF scheduling.

Communications with the UMED

The user-mode emulation DLL (UMED) interface is extended with the IGPUPMigration interface to expose the ability to save and validate content during a live migration.

HRESULT SaveImmutableGpup(

[in] PLUID DeviceLuid,

[in,out] UINT64 * Length,

[in,out] BYTE * SaveBuffer

);

HRESULT RestoreImmutableGpup(

[in] PLUID DeviceLuid,

[in] UINT64 Length,

[in] BYTE * RestoreBuffer

);

During the live migration preparation actions where the KMD is similarly called, the UMED has the opportunity to send over any information that might be useful to preparation of the UMED for the migration or validation that the environment supports the migration at the UMED level. It's an optional interface for UMEDs with the standard interface contracts for the UMED (threading and process context, restricted OS exposure, etc.). Its calling pattern mimics the KMD DDIs, with the two-phase save. There are no state flags in these calls, like other save/restore UMED interfaces as these should be valid and constant throughout the life of the device and its LUID.

The mutable state of the UMED is transferred in the existing Save/Restore interface. In the past, this interface was blocked from executing with GPU-P drivers, but is unblocked when the KMD reports support for LiveMigration. This tying of the UMED callout function and KMD capability is intentional. Live migration is how the system implements quick migration for the virtualization of these devices. The same sequence of tasks is done, and you can conceive of the quick migration (Save/Restore) as the special case of live migration where there's no active transfer. A UMED that supports Save/Restore still needs to have a KMD that supports the live migration DDIs. Similarly, the UMED must be aware of the IGPUPMigration interface and evaluate whether it's necessary in its design before the KMD could live migrate.

Virtualization of interrupts

The physical addressing of the guest interrupt management has to be virtualized in order to properly service MSI-X table access as the underlying hardware changes during the migration. The UMED must intercept the MSI-X interrupt table for all drivers that support live migration. Any reads or writes to the Message Upper Address and Message Address fields need to map to the actual hardware values. Dxgkrnl maintains the mapping of the virtualized (or guest) address and performs the substitution where needed in the call stack.

The OS manages the virtualization / mapping of the guest physical addresses that table reads or writes might refer to guest-side with the host physical addresses needed for actual interrupt servicing. This common path doesn't need separate UMED implementation or kernel forwarding, and the OS doesn't notify the UMED when the OS intercepts the table. The only requirement for the UMED is that the mitigations for the device need to be set for the BAR pages of the table.

However, in the kernel, Dxgkrnl wants the KMD to service the actual writes. KMD does so by implementing the added DxgkDdiWriteVirtualizedInterrupt callback function.

There should never be a need for a read because the UMD locally tracks writes (in virtualized / guest-translated form) so they don't require the expensive kernel jump. This tracking migrates with the virtual device.

DDI Sync and IRQL Contexts

| DDI | Sync Level | IRQL |

|---|---|---|

| DxgkDdiPrepareLiveMigration | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiEndLiveMigration | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiSaveImmutableMigrationData | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiSaveMutableMigrationData | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiRestoreImmutableMigrationData | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiRestoreMutableMigrationData | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiWriteVirtualizedInterrupt | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiSetVirtualGpuResources2 | 0 | PASSIVE |

| DxgkDdiSetVirtualFunctionPauseState | 0 | PASSIVE |

| IGPUPMigration::SaveImmutableGpup | 0 | PASSIVE |

| IGPUPMigration::RestoreImmutableGpup | 0 | PASSIVE |

Important Considerations for VF Scheduling

The efficiency of the transfer is strongly determined by the scheduling of the paging transfers on the PF. The more access to the paging engines of the device the PF can use to saturate the bus and get best throughput, the more performant the transfer is in general and the paused transfer specifically. The more content that can be captured and sent over in a given time, the better; at least up to network saturation.

It's preferable to have the change in scheduling only affect the paging engine and no other device resource, but not all VF scheduling designs might allow this. At a minimum, it's desired that the scheduling:

- Only take budget from the VF being migrated or from unassigned VF schedule.

- Not degrade performance for any other virtualizations on the machine.

Note, on the target side, these conditions can be much more easily met as the VF is paused the entire transfer and that whole budget is available. On the source side, it requires a balancing of the migration needs and the VM needs, with the ultimate need to meet the pause transfer goals.