Security Identifier

Windows uses the security identifier (SID) as the definitive value to distinguish security entities from one another. For example, a unique security identifier is assigned to each new account created for individual users on the system. For a file system, only this SID is used.

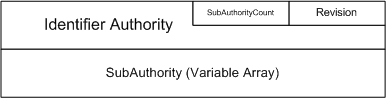

The following figure illustrates the security identifier structure.

In addition to unique SIDs, the Windows system defines a set of well known identifiers. For example, the local Administrator is a well-known SID.

Windows provides an in-kernel mechanism for converting between SIDs and user names within the kernel environment. These function calls are available from the ksecdd driver, which implements these functions by using user-mode helper services. Accordingly, their use within file systems must obey the usual rules for communication with user-mode services. These calls can't be used during paging file I/O.

Some of these functions are:

SecMakeSPN creates a service provider name string that can be used when communicating with specific security service providers.

SecMakeSPNEx is an augmented version of SecMakeSPN that was introduced in Windows XP.

SecMakeSPNEx2 is an augmented version of SecMakeSPNEx that is available starting in Windows Vista and Windows Server 2008.

SecLookupAccountSid returns an account name for a specified SID.

SecLookupAccountName retrieves the SID for a specified account name.

SecLookupWellKnownSid returns the correct SID for a specified well known SID type. This function is available on Windows Server 2003 and later.

In addition, any kernel driver can create a SID by using the following standard runtime library routines:

RtlInitializeSid initializes a buffer for a new SID.

RtlLengthSid determines the size of the SID stored within the given buffer.

RtlValidSid determines if the given SID buffer is a valid formatted buffer.

RtlLengthSid and RtlValidSid assume that the 8-byte fixed header for a SID is present. So a driver should check for this minimum length for a SID header before calling these functions.

While there are several other RTL functions, this list provides the primary functions necessary when constructing a SID.

The following code example demonstrates how to create a SID for the "local system" entity. The simpler SecLookupWellKnownSid function introduced in Windows Server 2003 could also be used.

{

//

// temporary stack-based storage for an SID

//

UCHAR sidBuffer[128];

PISID localSid = (PISID) sidBuffer;

SID_IDENTIFIER_AUTHORITY localSidAuthority =

SECURITY_NT_AUTHORITY;

//

// build the local system SID

//

RtlZeroMemory(sidBuffer, sizeof(sidBuffer));

localSid->Revision = SID_REVISION;

localSid->SubAuthorityCount = 1;

localSid->IdentifierAuthority = localSidAuthority;

localSid->SubAuthority[0] = SECURITY_LOCAL_SYSTEM_RID;

//

// make sure it is valid

//

if (!RtlValidSid(localSid)) {

DbgPrint("no dice - SID is invalid\n");

return(1);

}

}

The following code example demonstrates how to create a SID using the SecLookupWellKnownSid function for the "local system" entity:

{

UCHAR sidBuffer[128];

PISID localSid = (PISID) sidBuffer;

SIZE_T sidSize;

status = SecLookupWellKnownSid(WinLocalSid,

&localSid,

sizeof(sidBuffer),

&sidSize);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

//

// error handling

//

}

}

Either of these approaches are valid, although the latter code is preferred. These code examples use local buffers for storing the SID. These buffers can't be used outside the current call context. If the SID buffer needed to be persistent, the buffer should be allocated from pool memory.