Step 2: Create a Django app with views and page templates

Applies to: ![]() Visual Studio

Visual Studio ![]() Visual Studio for Mac

Visual Studio for Mac

Note

This article applies to Visual Studio 2017. If you're looking for the latest Visual Studio documentation, see Visual Studio documentation. We recommend upgrading to the latest version of Visual Studio. Download it here

Previous step: Create a Visual Studio project and solution

In the Visual Studio project, you only have the site-level components of a Django project now, which can run one or more Django apps. The next step is to create your first app with a single page.

In this step, you learn how to:

- Create a Django app with a single page (step 2-1)

- Run the app from the Django project (step 2-2)

- Render a view using HTML (step 2-3)

- Render a view using a Django page template (step 2-4)

Step 2-1: Create an app with a default structure

A Django app is a separate Python package that contains a set of related files for a specific purpose. A Django project can contain many apps, which help a web host to serve many separate entry points from a single domain name. For example, a Django project for a domain like contoso.com might contain one app for www.contoso.com, a second app for support.contoso.com, and a third app for docs.contoso.com. In this case, the Django project handles site-level URL routing and settings (in its urls.py and settings.py files). Each app has its own distinct styling and behavior through its internal routing, views, models, static files, and administrative interface.

A Django app usually begins with a standard set of files. Visual Studio provides templates to initialize a Django app within a Django project, along with an integrated menu command that serves the same purpose:

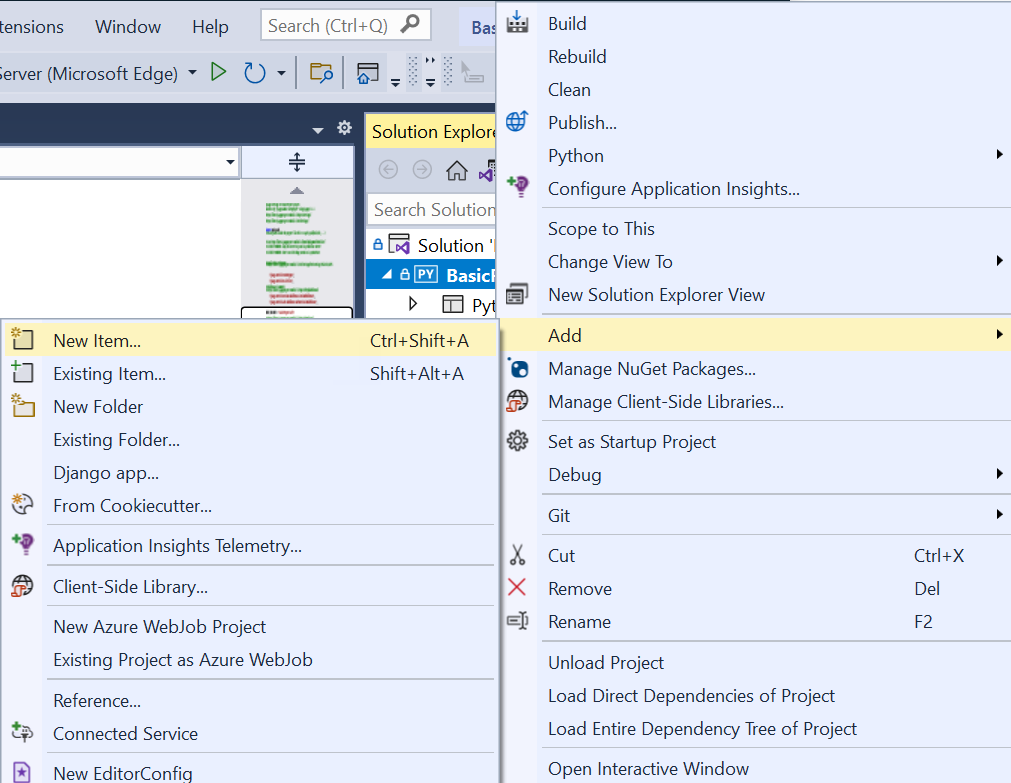

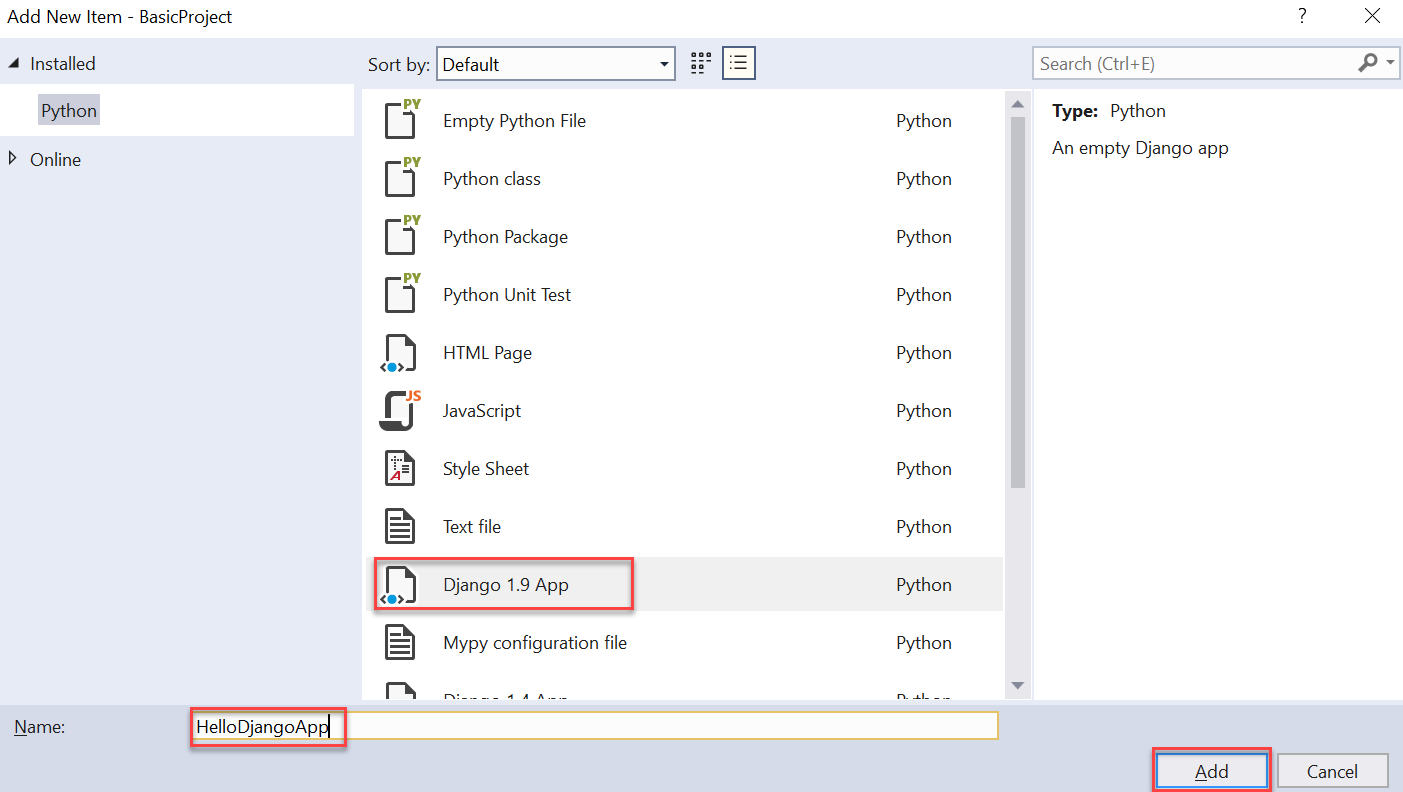

- Templates: In Solution Explorer, right-click the project and select Add > New item. In the Add New Item dialog, select the Django 1.9 App template, specify the app name in the Name field, and select Add.

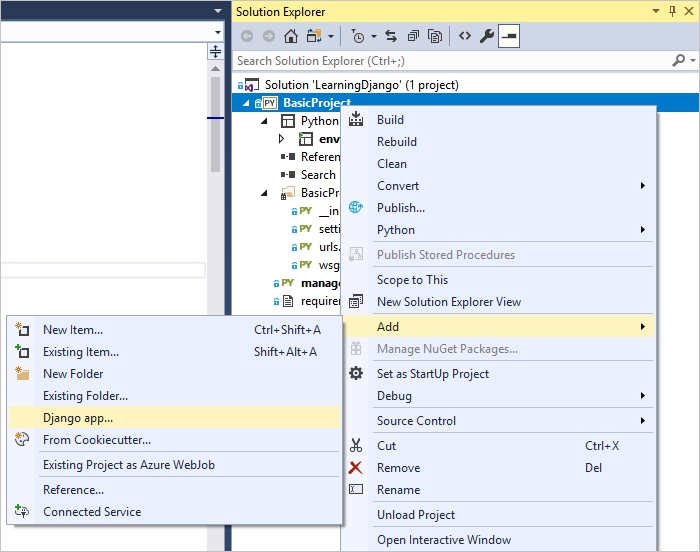

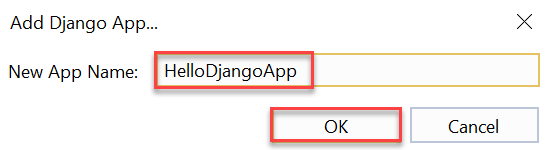

Integrated command: In Solution Explorer, right-click the project and select Add > Django app. This command prompts you for a name. Specify the app name in the New App Name field, and select OK.

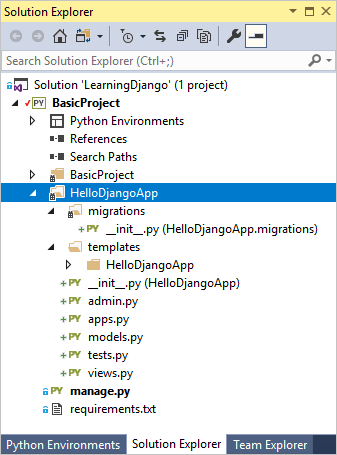

Using either method, create an app with the name "HelloDjangoApp". Now, the "HelloDjangoApp" folder is created in your project. The folder contains the following items:

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| __init__.py | The file that identifies the app as a package. |

| migrations | A folder in which Django stores scripts that update the database to align with changes to the models. Django's migration tools then apply the necessary changes to any previous version of the database so that it matches the current models. Using migrations, you keep your focus on your models and let Django handle the underlying database schema. Migrations are discussed in step 6; for now, the folder simply contains an __init__.py file (indicating that the folder defines its own Python package). |

| templates | A folder for Django page templates containing a single file index.html within a folder matching the app name. (In Visual Studio 2017 15.7 and earlier, the file is contained directly under templates and step 2-4 instructs you to create the subfolder.) Templates are blocks of HTML into which views can add information to dynamically render a page. Page template "variables," such as {{ content }} in index.html, are placeholders for dynamic values as explained later in this article (step 2). Typically Django apps create a namespace for their templates by placing them in a subfolder that matches the app name. |

| admin.py | The Python file in which you extend the app's administrative interface (see step 6), which is used to seed and edit data in a database. Initially, this file contains only the statement, from django.contrib import admin. By default, Django includes a standard administrative interface through entries in the Django project's settings.py file, which you can turn on by uncommenting existing entries in urls.py. |

| apps.py | A Python file that defines a configuration class for the app (see below, after this table). |

| models.py | Models are data objects, identified by functions, through which views interact with the app's underlying database (see step 6). Django provides the database connection layer so that apps don't need to concern themselves with those details. The models.py file is a default place in which to create your models, and initially contains only the statement, from django.db import models. |

| tests.py | A Python file that contains the basic structure of unit tests. |

| views.py | Views are what you typically think of as web pages, which take an HTTP request and return an HTTP response. Views typically render as HTML that web browsers know how to display, but a view doesn't necessarily have to be visible (like an intermediate form). A view is defined by a Python function whose responsibility is to render the HTML to send to the browser. The views.py file is a default place in which to create views, and initially contains only the statement, from django.shortcuts import render. |

When you use the name "HelloDjangoApp," the contents of the apps.py file appears as:

from django.apps import AppConfig

class HelloDjangoAppConfig(AppConfig):

name = 'HelloDjango'

Question: Is creating a Django app in Visual Studio any different from creating an app on the command line?

Answer: Running the Add > Django app command or using Add > New Item with a Django app template produces the same files as the Django command manage.py startapp <app_name>. The benefit of creating an app in Visual Studio is that the app folder and all its files are automatically integrated in the project. You can use the same Visual Studio command to create any number of apps in your project.

Step 2-2: Run the app from the Django project

At this point, if you run the project again in Visual Studio (using the toolbar button or Debug > Start Debugging), you'll still see the default page. No app content appears because you need to define an app-specific page and add the app to the Django project:

In the HelloDjangoApp folder, modify the views.py file to define a view named "index":

from django.shortcuts import render from django.http import HttpResponse def index(request): return HttpResponse("Hello, Django!")In the BasicProject folder (created in step 1), modify the urls.py file to match the following code (you can keep the instructive comment, if you like):

from django.conf.urls import include, url import HelloDjangoApp.views # Django processes URL patterns in the order they appear in the array urlpatterns = [ url(r'^$', HelloDjangoApp.views.index, name='index'), url(r'^home$', HelloDjangoApp.views.index, name='home'), ]Each URL pattern describes the views to which Django routes specific site-relative URLs (that is, the portion that follows

https://www.domain.com/). The first entry inurlPatternsthat starts with the regular expression^$is the routing for the site root, "/". The second entry,^home$specifically routes "/home". You can have multiple routings to the same view.Run the project again to see the message Hello, Django! as defined by the view. When you're done, stop the server.

Commit to source control

After making changes to your code and testing successfully, you can review and commit to the source control. In later steps, when this tutorial reminds you to commit to source control again, you can refer to this section.

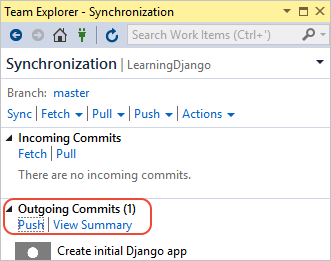

Select the changes button along the bottom of Visual Studio (circled below), to navigate to Team Explorer.

In Team Explorer, enter a commit message like "Create initial Django app" and select Commit All. When the commit is complete, you see a message Commit <hash> created locally. Sync to share your changes with the server. If you want to push changes to your remote repository, select Sync, and then select Push under Outgoing Commits. You can also accumulate multiple local commits before pushing to remote.

Question: What is the 'r' prefix before the routing strings for?

Answer: The 'r' prefix on a string in Python means "raw," which instructs Python to not escape any characters within the string. The regular expressions use many special characters. Using the 'r' prefix make the strings much easier to read than the escape characters '\'.

Question: What do the ^ and $ characters mean in the URL routing entries?

Answer: In the regular expressions that define URL patterns, ^ means "start of line" and $ means "end of line," wherein the URLs are relative to the site root (the part that follows https://www.domain.com/). The regular expression ^$ effectively means "blank" and matches the full URL https://www.domain.com/ (nothing added to the site root). The pattern ^home$ matches exactly https://www.domain.com/home/. (Django doesn't use the trailing / in pattern matching.)

If you don't use a trailing $ in a regular expression, as with ^home, then URL pattern matches any URL that begins with "home" such as "home", "homework", "homestead", and "home192837".

To experiment with different regular expressions, try online tools such as regex101.com at pythex.org.

Step 2-3: Render a view using HTML

The index function that you have in views.py file generates a plain-text HTTP response for the page. Most real-world web pages respond with rich HTML pages that often incorporate live data. Indeed, the primary reason to define a view using a function is to generate the content dynamically.

As the argument to HttpResponse is just a string, you can build up any HTML you like within a string. As a simple example, replace the index function with the following code (keep the existing from statements). The index function will then generate an HTML response using dynamic content that's updated every time you refresh the page.

from datetime import datetime

def index(request):

now = datetime.now()

html_content = "<html><head><title>Hello, Django</title></head><body>"

html_content += "<strong>Hello Django!</strong> on " + now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X")

html_content += "</body></html>"

return HttpResponse(html_content)

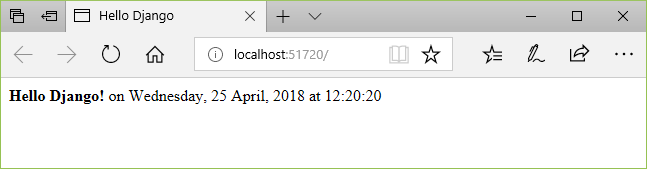

Now, run the project again to see a message like "Hello Django! on Monday 16 April 2018 at 16:28:10". Refresh the page to update the time and confirm that the content is being generated with each request. When you're done, stop the server.

Tip

A shortcut to stopping and restarting the project is to use the Debug > Restart menu command (Ctrl+Shift+F5) or the Restart button on the debugging toolbar:

Step 2-4: Render a view using a page template

Generating HTML in code works fine for small pages. However, as pages get more sophisticated you need to maintain the static HTML parts of your page (along with references to CSS and JavaScript files) as "page templates." You can then insert the dynamic, code-generated content to the page templates. In the previous section, only the date and time from the now.strftime call is dynamic, which means all the other content can be placed in a page template.

A Django page template is a block of HTML that contains multiple replacement tokens called "variables." The variables are delineated by {{ and }}, for example, {{ content }}. Django's template module then replaces variables with dynamic content that you provide in code.

The following steps demonstrate the use of page templates:

Under the BasicProject folder, which contains the Django project, open the settings.py file. Add the app name, "HelloDjangoApp," to the

INSTALLED_APPSlist. Adding the app to the list tells the Django project that there's a folder of "HelloDjangoApp" name containing an app:INSTALLED_APPS = [ 'HelloDjangoApp', # Other entries... ]In the settings.py file, ensure that the

TEMPLATESobject contains the following line (included by default). The following code instructs Django to look for templates in an installed app's templates folder:'APP_DIRS': True,In the HelloDjangoApp folder, open the templates/HelloDjangoApp/index.html page template file (or templates/index.html in VS 2017 15.7 and earlier), to observe that it contains one variable,

{{ content }}:<html> <head><title></title></head> <body> {{ content }} </body> </html>In the HelloDjangoApp folder, open the views.py file and replace the

indexfunction with the following code that uses thedjango.shortcuts.renderhelper function. Therenderhelper provides a simplified interface for working with page templates. Ensure that you keep all the existingfromstatements.from django.shortcuts import render # Added for this step def index(request): now = datetime.now() return render( request, "HelloDjangoApp/index.html", # Relative path from the 'templates' folder to the template file # "index.html", # Use this code for VS 2017 15.7 and earlier { 'content': "<strong>Hello Django!</strong> on " + now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X") } )The first argument to

render, is the request object, followed by the relative path to the template file within the app's templates folder. A template file is named for the view it supports, if appropriate. The third argument torenderis then a dictionary of variables that the template refers to. You can include objects in the dictionary, in that case a variable in the template can refer to{{ object.property }}.Run the project and observe the output. You should see a similar message as in step 2-2, indicating that the template works.

Observe, that the HTML you used in the

contentproperty renders only as plain text because therenderfunction automatically escapes the HTML. Automatic escape prevents accidental vulnerabilities to injection attacks. Developers often gather input from one page and use it as a value in another through a template placeholder. Escaping also serves as a reminder that it's best to keep the HTML in the page template and out of the code. Also, it's simple to create more variables where needed. For example, change the index.html file with templates to match the following markup. The following markup adds a page title and keeps all the formatting in the page template:<html> <head> <title>{{ title }}</title> </head> <body> <strong>{{ message }}</strong>{{ content }} </body> </html>Then, to provide values for all the variables in the page template, write the

indexview function as specified here:def index(request): now = datetime.now() return render( request, "HelloDjangoApp/index.html", # Relative path from the 'templates' folder to the template file # "index.html", # Use this code for VS 2017 15.7 and earlier { 'title' : "Hello Django", 'message' : "Hello Django!", 'content' : " on " + now.strftime("%A, %d %B, %Y at %X") } )Stop the server and restart the project. Ensure that the page renders properly:

Visual Studio 2017 version 15.7 and earlier: As a final step, move your templates into a subfolder named the same as your app. The subfolder creates a namespace and avoids potential conflicts with other apps you might add to the project. (The templates in VS 2017 15.8+ do this for you automatically.) That is, create a subfolder in templates named HelloDjangoApp, move the index.html file into that subfolder, and modify the

indexview function. Theindexview function will refer to the template's new path, HelloDjangoApp/index.html. Then run the project, verify that the page renders properly, and stop the server.Commit your changes to source control and update your remote repository, if needed, as described under step 2-2.

Question: Do page templates have to be in a separate file?

Answer: Usually, templates are maintained in separate HTML files. You can also use an inline template. To maintain a clean separation between markup and code, using a separate file is recommended.

Question: Templates must use the .html file extension?

Answer: The .html extension for page template files is entirely optional, as you identify the exact relative path to the file in the second argument to the render function. However, Visual Studio (and other editors) provides the features like code completion and syntax coloration with .html files, which outweighs the fact that the page templates aren't strictly HTML.

In fact, when you're working with a Django project, Visual Studio automatically detects the HTML file that has a Django template and provides certain autocomplete features. For example, when you start typing a Django page template comment, {#, Visual Studio automatically gives you the closing #} characters. The Comment Selection and Uncomment Selection commands (on the Edit > Advanced menu and on the toolbar) also use the template comments instead of HTML comments.

Question: When I run the project, I see an error that the template can't be found. What's wrong?

Answer: If you see errors that the template can't be found, ensure that you've added the app to the Django project's settings.py in the INSTALLED_APPS list. Without that entry, Django won't know what to look in the app's templates folder.

Question: Why is template namespacing important?

Answer: When Django looks for a template referred to in the render function, it uses the first file that matches the relative path. If you have multiple Django apps in the same project with same folder structures for templates, it's likely that one app will unintentionally use a template from another app. To avoid such errors, always create a subfolder under an app's templates folder that matches the name of the app to avoid any duplication.

Next steps

Go deeper

- Writing your first Django app, part 1 - views (docs.djangoproject.com)

- For more capabilities of Django templates, such as includes and inheritance, see The Django template language (docs.djangoproject.com)

- Regular expression training on inLearning (LinkedIn)

- Tutorial source code on GitHub: Microsoft/python-sample-vs-learning-django