Why use a microservices approach to building applications

For software developers, factoring an application into component parts is nothing new. Typically, a tiered approach is used, with a back-end store, middle-tier business logic, and a front-end user interface (UI). What has changed over the last few years is that developers are building distributed applications for the cloud.

Here are some changing business needs:

- A service that's built and operated at scale to reach customers in new geographic regions.

- Faster delivery of features and capabilities to respond to customer demands in an agile way.

- Improved resource utilization to reduce costs.

These business needs are affecting how we build applications.

For more information about the Azure approach to microservices, see Microservices: An application revolution powered by the cloud.

Monolithic vs. microservices design approach

Applications evolve over time. Successful applications evolve by being useful to people. Unsuccessful applications don't evolve and are eventually deprecated. Here's the question: how much do you know about your requirements today and what they'll be in the future? For example, let's say you're building a reporting application for a department in your company. You're sure the application applies only within the scope of your company and that the reports won't be kept long. Your approach will be different from that of, say, building a service that delivers video content to tens of millions of customers.

Sometimes, getting something out the door as a proof of concept is the driving factor. You know the application can be redesigned later. There's little point in over-engineering something that never gets used. On the other hand, when companies build for the cloud, the expectation is growth and usage. Growth and scale are unpredictable. We want to prototype quickly while also knowing that we're on a path that can handle future success. This is the lean startup approach: build, measure, learn, and iterate.

During the client/server era, we tended to focus on building tiered applications by using specific technologies in each tier. The term monolithic application has emerged to describe these approaches. The interfaces tended to be between the tiers, and a more tightly coupled design was used between components within each tier. Developers designed and factored classes that were compiled into libraries and linked together into a few executable files and DLLs.

There are benefits to a monolithic design approach. Monolithic applications are often simpler to design, and calls between components are faster because these calls are often over interprocess communication (IPC). Also, everyone tests a single product, which tends to be a more efficient use of human resources. The downside is that there's a tight coupling between tiered layers, and you can't scale individual components. If you need to do fixes or upgrades, you have to wait for others to finish their testing. It's harder to be agile.

Microservices address these downsides and more closely align with the preceding business requirements. But they also have both benefits and liabilities. The benefits of microservices are that each one typically encapsulates simpler business functionality, which you can scale out or in, test, deploy, and manage independently. One important benefit of a microservices approach is that teams are driven more by business scenarios than by technology. Smaller teams develop a microservice based on a customer scenario and use any technologies that they want to use.

In other words, the organization doesn’t need to standardize tech to maintain microservice applications. Individual teams that own services can do what makes sense for them based on team expertise or what’s most appropriate to solve the problem. In practice, a set of recommended technologies, like a particular NoSQL store or web application framework, is preferable.

The downside of microservices is that you have to manage more separate entities and deal with more complex deployments and versioning. Network traffic between the microservices increases, as do the corresponding network latencies. Lots of chatty, granular services can cause a performance nightmare. Without tools to help you view these dependencies, it's hard to see the whole system.

Standards make the microservices approach work by specifying how to communicate and tolerating only the things you need from a service, rather than rigid contracts. It's important to define these contracts up front in the design because services update independently of each other. Another description coined for designing with a microservices approach is “fine-grained service-oriented architecture (SOA).”

At its simplest, the microservices design approach is about a decoupled federation of services, with independent changes to each and agreed-upon standards for communication.

As more cloud applications are produced, people have discovered that this decomposition of the overall application into independent, scenario-focused services is a better long-term approach.

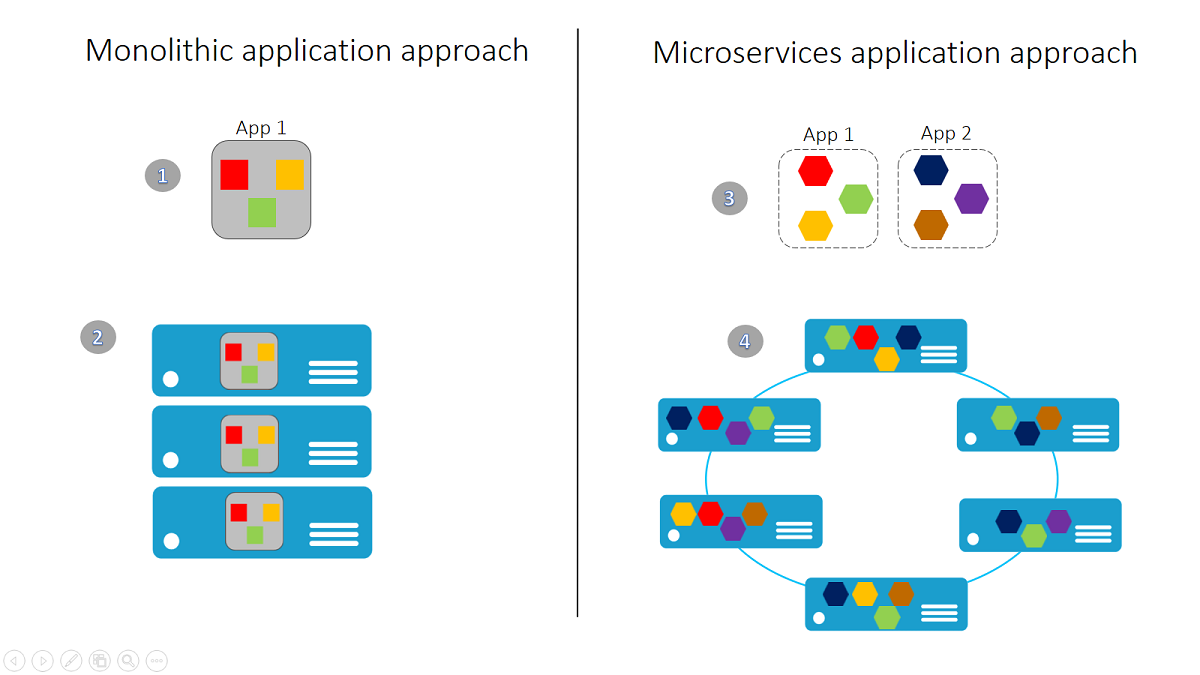

Comparison between application development approaches

A monolithic application contains domain-specific functionality and is normally divided into functional layers like web, business, and data.

You scale a monolithic application by cloning it on multiple servers/virtual machines/containers.

A microservice application separates functionality into separate smaller services.

The microservices approach scales out by deploying each service independently, creating instances of these services across servers/virtual machines/containers.

Designing with a microservices approach isn't appropriate for all projects, but it does align more closely with the business objectives described earlier. Starting with a monolithic approach might make sense if you know you'll have the opportunity to rework the code later into a microservices design. More commonly, you begin with a monolithic application and slowly break it up in stages, starting with the functional areas that need to be more scalable or agile.

When you use a microservices approach, you compose your application of many small services. These services run in containers that are deployed across a cluster of machines. Smaller teams develop a service that focuses on a scenario and independently test, version, deploy, and scale each service so the entire application can evolve.

What is a microservice?

There are different definitions of microservices. But most of these characteristics of microservices are widely accepted:

- Encapsulate a customer or business scenario. What problem are you solving?

- Developed by a small engineering team.

- Written in any programming language, using any framework.

- Consist of code, and optionally state, both of which are independently versioned, deployed, and scaled.

- Interact with other microservices over well-defined interfaces and protocols.

- Have unique names (URLs) that are used to resolve their location.

- Remain consistent and available in the presence of failures.

To sum that up:

Microservice applications are composed of small, independently versioned, and scalable customer-focused services that communicate with each other over standard protocols with well-defined interfaces.

Written in any programming language, using any framework

As developers, we want to be free to choose a language or framework, depending on our skills and the needs of the service that we're creating. For some services, you might value the performance benefits of C++ above anything else. For others, the ease of managed development that you get from C# or Java might be more important. In some cases, you might need to use a specific partner library, data storage technology, or method for exposing the service to clients.

After you choose a technology, you need to consider the operational or life-cycle management and scaling of the service.

Allows code and state to be independently versioned, deployed, and scaled

No matter how you write your microservices, the code, and optionally the state, should independently deploy, upgrade, and scale. This problem is hard to solve because it comes down to your choice of technologies. For scaling, understanding how to partition (or shard) both the code and the state is challenging. When the code and state use different technologies, which is common today, the deployment scripts for your microservice need to be able to scale them both. This separation is also about agility and flexibility, so you can upgrade some of the microservices without having to upgrade all of them at once.

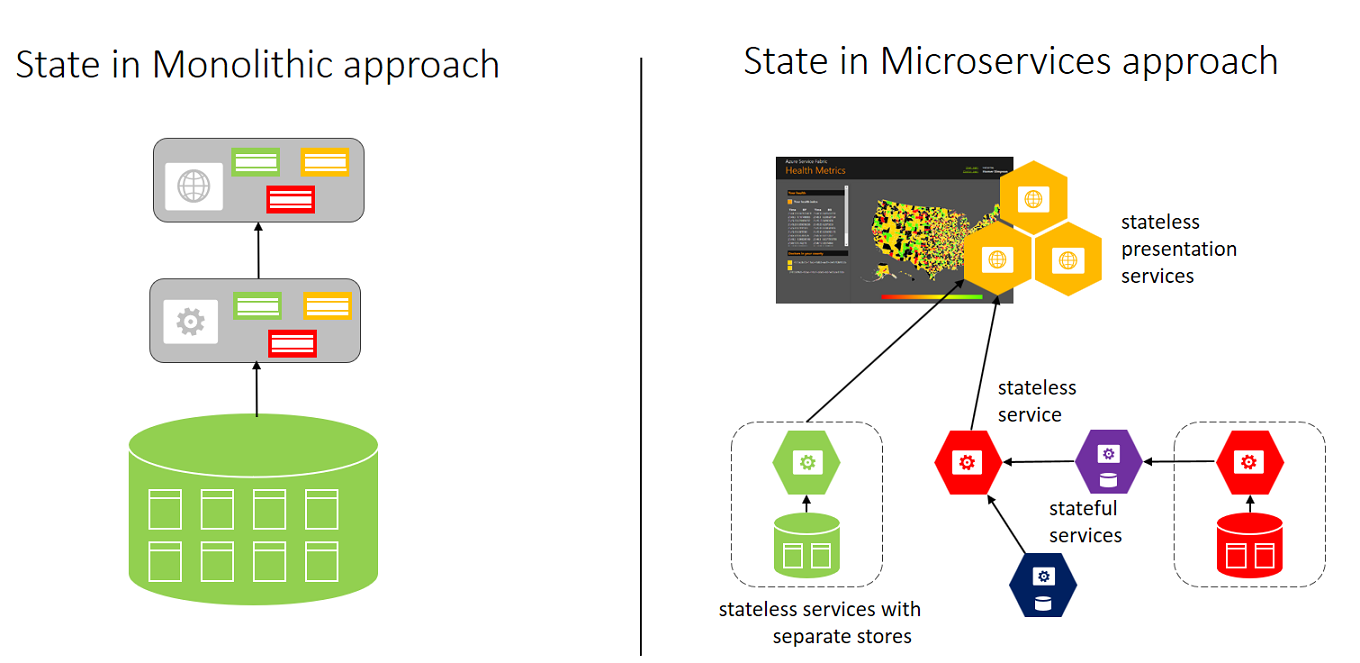

Let's return to our comparison of the monolithic and microservices approaches for a moment. This diagram shows the differences in the approaches to storing state:

State storage for the two approaches

The monolithic approach, on the left, has a single database and tiers of specific technologies.

The microservices approach, on the right, has a graph of interconnected microservices where state is typically scoped to the microservice and various technologies are used.

In a monolithic approach, the application typically uses a single database. The advantage to using one database is that it's in a single location, which makes it easy to deploy. Each component can have a single table to store its state. Teams need to strictly separate state, which is a challenge. Inevitably, someone will be tempted to add a column to an existing customer table, do a join between tables, and create dependencies at the storage layer. After this happens, you can't scale individual components.

In the microservices approach, each service manages and stores its own state. Each service is responsible for scaling both code and state together to meet the demands of the service. A downside is that when you need to create views, or queries, of your application’s data, you need to query across multiple state stores. This problem is typically solved by a separate microservice that builds a view across a collection of microservices. If you need to run multiple impromptu queries on the data, you should consider writing each microservice’s data to a data warehousing service for offline analytics.

Microservices are versioned. It's possible for different versions of a microservice to run side by side. A newer version of a microservice could fail during an upgrade and need to be rolled back to an earlier version. Versioning is also helpful for A/B testing, where different users experience different versions of the service. For example, it's common to upgrade a microservice for a specific set of customers to test new functionality before rolling it out more widely.

Interacts with other microservices over well-defined interfaces and protocols

Over the past 10 years, extensive information has been published describing communication patterns in service-oriented architectures. Generally, service communication uses a REST approach with HTTP and TCP protocols and XML or JSON as the serialization format. From an interface perspective, it's about taking a web design approach. But nothing should stop you from using binary protocols or your own data formats. Just be aware that people will have a harder time using your microservices if these protocols and formats aren't openly available.

Has a unique name (URL) used to resolve its location

Your microservice needs to be addressable wherever it's running. If you're thinking about machines and which one is running a particular microservice, things can go bad quickly.

In the same way that DNS resolves a particular URL to a particular machine, your microservice needs a unique name so that its current location is discoverable. Microservices need addressable names that are independent of the infrastructure they're running on. This implies that there's an interaction between how your service is deployed and how it's discovered, because there needs to be a service registry. When a machine fails, the registry service needs to tell you where the service was moved to.

Remains consistent and available in the presence of failures

Dealing with unexpected failures is one of the hardest problems to solve, especially in a distributed system. Much of the code that we write as developers is for handling exceptions. During testing, we also spend the most time on exception handling. The process is more involved than writing code to handle failures. What happens when the machine on which the microservice is running fails? You need to detect the failure, which is a hard problem on its own. But you also need to restart your microservice.

For availability, a microservice needs to be resilient to failures and able to restart on another machine. In addition to these resiliency requirements, data shouldn't be lost, and data needs to remain consistent.

Resiliency is hard to achieve when failures happen during an application upgrade. The microservice, working with the deployment system, doesn't need to recover. It needs to determine whether it can continue to move forward to the newer version or roll back to a previous version to maintain a consistent state. You need to consider a few questions, like whether enough machines are available to keep moving forward and how to recover previous versions of the microservice. To make these decisions, you need the microservice to emit health information.

Reports health and diagnostics

It might seem obvious, and it's often overlooked, but a microservice needs to report its health and diagnostics. Otherwise, you have little insight into its health from an operations perspective. Correlating diagnostic events across a set of independent services, and dealing with machine clock skews to make sense of the event order, is challenging. In the same way that you interact with a microservice over agreed-upon protocols and data formats, you need to standardize how to log health and diagnostic events that will ultimately end up in an event store for querying and viewing. With a microservices approach, different teams need to agree on a single logging format. There needs to be a consistent approach to viewing diagnostic events in the application as a whole.

Health is different from diagnostics. Health is about the microservice reporting its current state to take appropriate actions. A good example is working with upgrade and deployment mechanisms to maintain availability. Though a service might be currently unhealthy because of a process crash or machine reboot, the service might still be operational. The last thing you need is to make the situation worse by starting an upgrade. The best approach is to investigate first or allow time for the microservice to recover. Health events from a microservice help us make informed decisions and, in effect, help create self-healing services.

Guidance for designing microservices on Azure

Visit the Azure architecture center for guidance on designing and building microservices on Azure.

Service Fabric as a microservices platform

Azure Service Fabric emerged when Microsoft transitioned from delivering boxed products, which were typically monolithic, to delivering services. The experience of building and operating large services, like Azure SQL Database and Azure Cosmos DB, shaped Service Fabric. The platform evolved over time as more services adopted it. Service Fabric had to run not only in Azure but also in standalone Windows Server deployments.

The aim of Service Fabric is to solve the hard problems of building and running a service and to use infrastructure resources efficiently, so teams can solve business problems by using a microservices approach.

Service Fabric helps you build applications that use a microservices approach by providing:

- A platform that provides system services to deploy, upgrade, detect, and restart failed services, discover services, route messages, manage state, and monitor health.

- The ability to deploy applications either running in containers or as processes. Service Fabric is a container and process orchestrator.

- Productive programming APIs to help you build applications as microservices: ASP.NET Core, Reliable Actors, and Reliable Services. For example, you can get health and diagnostics information, or you can take advantage of built-in high availability.

Service Fabric is agnostic about how you build your service, and you can use any technology. But it does provide built-in programming APIs that make it easier to build microservices.

Migrating existing applications to Service Fabric

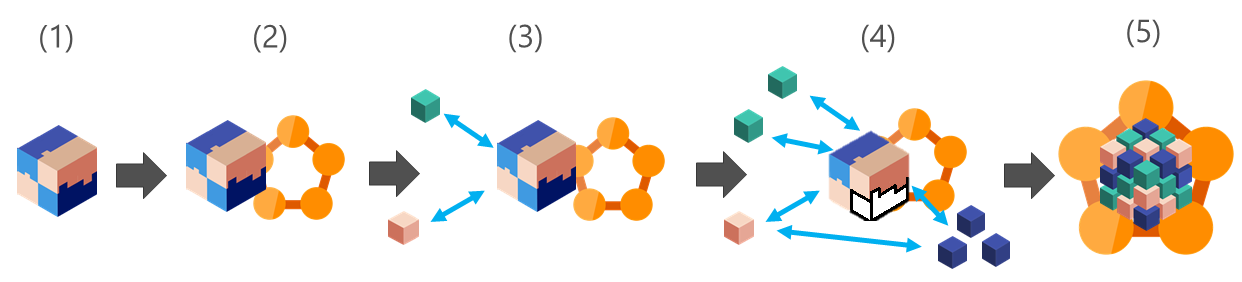

Service Fabric allows you to reuse existing code and modernize it with new microservices. There are five stages to application modernization, and you can start and stop at any stage. The stages are:

- Start with a traditional monolithic application.

- Migrate. Use containers or guest executables to host existing code in Service Fabric.

- Modernize. Add new microservices alongside existing containerized code.

- Innovate. Break the monolithic application into microservices based on need.

- Transform applications into microservices. Transform existing monolithic applications or build new greenfield applications.

Remember, you can start and stop at any of these stages. You don't have to progress to the next stage.

Let's look at examples for each of these stages.

Migrate

For two reasons, many companies are migrating existing monolithic applications into containers:

- Cost reduction, either due to consolidation and removal of existing hardware or due to running applications at higher density.

- A consistent deployment contract between development and operations.

Cost reductions are straightforward. At Microsoft, many existing applications are being containerized, leading to millions of dollars in savings. Consistent deployment is harder to evaluate but equally important. It means that developers can choose the technologies that suit them, but operations will accept only a single method for deploying and managing the applications. It alleviates operations from having to deal with the complexity of supporting different technologies without forcing developers to choose only certain ones. Essentially, every application is containerized into self-contained deployment images.

Many organizations stop here. They already have the benefits of containers, and Service Fabric provides the complete management experience, including deployment, upgrades, versioning, rollbacks, and health monitoring.

Modernize

Modernization is the addition of new services alongside existing containerized code. If you're going to write new code, it's best to take small steps down the microservices path. This could mean adding a new REST API endpoint or new business logic. In this way, you start the process of building new microservices and practice developing and deploying them.

Innovate

A microservices approach accommodates changing business needs. At this stage, you need to decide whether to start splitting the monolithic application into services, or innovating. A classic example here is when a database that you're using as a workflow queue becomes a processing bottleneck. As the number of workflow requests increases, the work needs to be distributed for scale. Take that particular piece of the application that's not scaling, or that needs to be updated more frequently, and split it out as a microservice and innovate.

Transform applications into microservices

At this stage, your application is fully composed of (or split into) microservices. To reach this point, you've made the microservices journey. You can start here, but to do so without a microservices platform to help you requires a significant investment.

Are microservices right for my application?

Maybe. At Microsoft, as more teams began to build for the cloud for business reasons, many of them realized the benefits of taking a microservice-like approach. Bing, for example, has been using microservices for years. For other teams, the microservices approach was new. Teams found that there were hard problems to solve outside of their core areas of strength. This is why Service Fabric gained traction as the technology for building services.

The objective of Service Fabric is to reduce the complexities of building microservice applications so that you don't have to go through as many costly redesigns. Start small, scale when needed, deprecate services, add new ones, and evolve with customer usage. We also know that there are many other problems yet to be solved to make microservices more approachable for most developers. Containers and the actor programming model are examples of small steps in that direction. We're sure more innovations will emerge to make a microservices approach easier.