RAG chunk enrichment phase

After you break your documents into a collection of chunks, the next step is to enrich each chunk by cleaning it and augmenting it with metadata. Cleaning the chunks enables you to achieve better matches for semantic queries in a vector search. Adding metadata enables you to support searches of the chunks that go beyond semantic searches. Both cleaning and augmenting involve extending the schema for the chunk.

This article discusses various ways to augment your chunks, including some common cleaning operations that you can perform on chunks to improve vector comparisons. It also describes some common metadata fields that you can add to your chunks to augment your search index.

This article is part of a series. Here's the introduction.

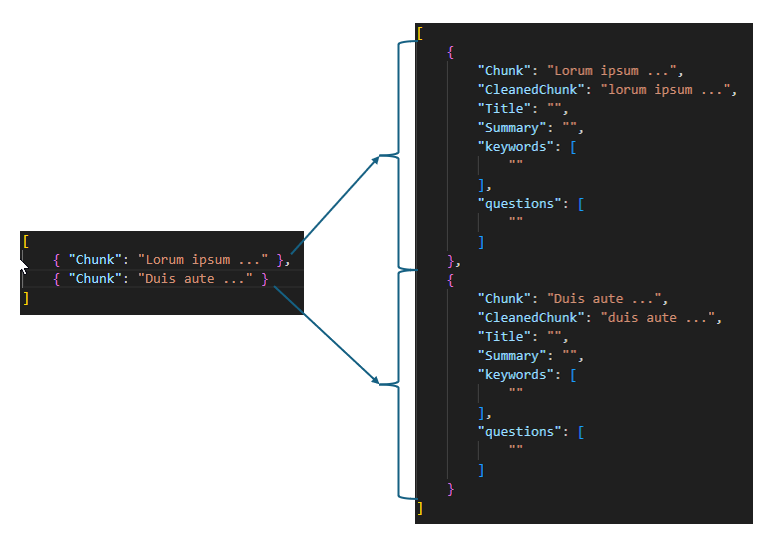

The following code sample shows chunks that are enriched with data.

Cleaning data

Chunking your data helps your workload find the most relevant chunks, typically through vectorizing those chunks and storing them in a vector database. An optimized vector search returns only the rows in the database that have the closest semantic matches to the query. The goal of cleaning the data is to support closeness matches by eliminating potential differences that aren't material to the semantics of the text. Following are some common cleaning procedures.

Note

You should return the original, uncleaned chunk as the query result, so you should add an additional field to store the cleaned and vectorized data.

Implement lowercasing strategies. Lowercasing allows words that are capitalized, such as words at the beginning of a sentence, to match corresponding words within a sentence. Embeddings are typically case-sensitive, so "Cheetah" and "cheetah" would result in a different vector for the same logical word. For example, for the embedded query "what is faster, a cheetah or a puma?" the embedding "cheetahs are faster than pumas" is a closer match than "Cheetahs are faster than pumas." Some lowercasing strategies lowercase all words, including proper nouns, while other strategies lowercase only the first words in sentences.

Remove stop words. Stop words are words like "a", "an," and "the." You can remove stop words to reduce the dimensionality of the resulting vector. If you remove stop words in the previous example, "a cheetah is faster than a puma" and "the cheetah is faster than the puma" are vectorially equal to "cheetah faster puma." However, it's important to understand that some stop words hold semantic meaning. For example, "not" might be considered a stop word, but it holds significant semantic meaning. You need to test to determine the effect of removing stop words.

Fix spelling mistakes. A misspelled word doesn't match with the correctly spelled word in the embedding model. For example, "cheatah" isn't the same as "cheetah" in the embedding. You should fix spelling mistakes to address this problem.

Remove Unicode characters. Removing Unicode characters can reduce noise in your chunks and reduce dimensionality. Like stop words, some Unicode characters might contain relevant information. It's important to conduct testing to understand the impact of removing Unicode characters.

Normalize text. Normalizing text according to standards like expanding abbreviations, converting numbers to words, and expanding contractions, for example, expanding "I'm" to "I am," can help increase the performance of vector searches.

Augmenting chunks

Semantic searches against the vectorized chunks work well for some types of queries but not as well for others. Depending upon the types of queries you need to support, you might need to augment your chunks with additional information. The additional metadata fields are all stored in the same row as your embeddings and can be used in the search solution either as filters or as part of a search.

The following image shows the JSON of fully enriched content and describes how the metadata might be used by a search platform.

The metadata columns that you need to add depend on your problem domain, including the type of data you have and the types of queries you want to support. You need to analyze the user experience, available data, and result quality you're trying to achieve. From there, you can determine what metadata might help you address your workload's requirements.

Following are some common metadata fields, along with the original chunk text, some guidance about their potential uses, and tools or techniques that are commonly used to generate the metadata content.

ID. An ID uniquely identifies a chunk. A unique ID is useful during processing to determine whether a chunk already exists in the store. An ID can be a hash of some key field. Tools: A hashing library.

Title. A title is a useful return value for a chunk. It provides a quick summary of the content in the chunk. The summary can also be useful to query with an indexed search because it can contain keywords for matching. Tools: A language model.

Summary. The summary is similar to the title in that it's a common return value and can be used in indexed searches. Summaries are generally longer than titles. Tools: A language model.

Rephrasing of the chunk. Rephrasing of a chunk can be helpful as a vector search field because rephrasing captures variations in language, such as synonyms and paraphrasing. Tools: A language model.

Keywords. Keyword searches are useful for data that's noncontextual, for searching for an exact match, and when a specific term or value is important. For example, an auto manufacturer might have reviews or performance data for each of its models for multiple years. "Review for product X for year 2009" is semantically like "Review for product X for 2010" and "Review for product Y for 2009." In this case, it's more effective to match on keywords for the product and year. Tools: A language model, RAKE, KeyBERT, multi-rake.

Entities. Entities are specific pieces of information, like people, organizations, and locations. Like keywords, entities are good for exact match searches or when specific entities are important. Tools: spaCy, Stanford Named Entity Recognizer (Stanford NER), scikit-learn, Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK).

Cleaned chunk text. The text of the cleaned chunk. Tools: A language model.

Questions that the chunk can answer. Sometimes, the query that's embedded isn't a close match to the chunk that's embedded. For example, the query might be small relative to the chunk size. It might be better to formulate the queries that the chunk can answer and do a vector search between the user's actual query and the pre-formulated queries. Tools: A language model.

Source. The source of the chunk can be valuable as a return for queries. Returning the source allows the querier to cite the original source.

Language. The language of the chunk can be useful as a filter in queries.

The cost of augmenting

The use of some language models for augmenting chunks can be expensive. You need to calculate the cost of each enrichment that you're considering and multiply it by the estimated number of chunks over time. You should use this information, along with your testing of the enriched fields, to determine the best business decision.