Minimize model errors with cost functions

The learning process repeatedly alters a model until it can make high-quality estimates. To determine how well a model is performing, the learning process uses mathematics in the form of a cost function. The cost function is also known as an objective function. To understand what a cost function is, let's break it down a little.

Error, cost, and loss

In supervised learning, error, cost, and loss all refer to the number of mistakes that a model makes in predicting one or more labels.

These three terms are used loosely in machine learning, which can cause some confusion. For the sake of simplicity, we use them interchangeably here. Cost is calculated through mathematics; it isn't a qualitative judgment. For example, if a model predicts a daily temperature of 40°F, but the actual value is 35°F, we might say it has an error of 5°F.

Minimizing cost is our goal

Because cost indicates how badly a model works, our goal is to have zero cost. In other words, we want to train the model to make no mistakes at all. This idea is often impossible, though, so instead we set a slightly more nebulous goal of training the model to have the lowest cost possible.

Because of this goal, how we calculate cost dictates what the model tries to learn. In the preceding example, we defined cost as the error in estimating temperature.

What is a cost function?

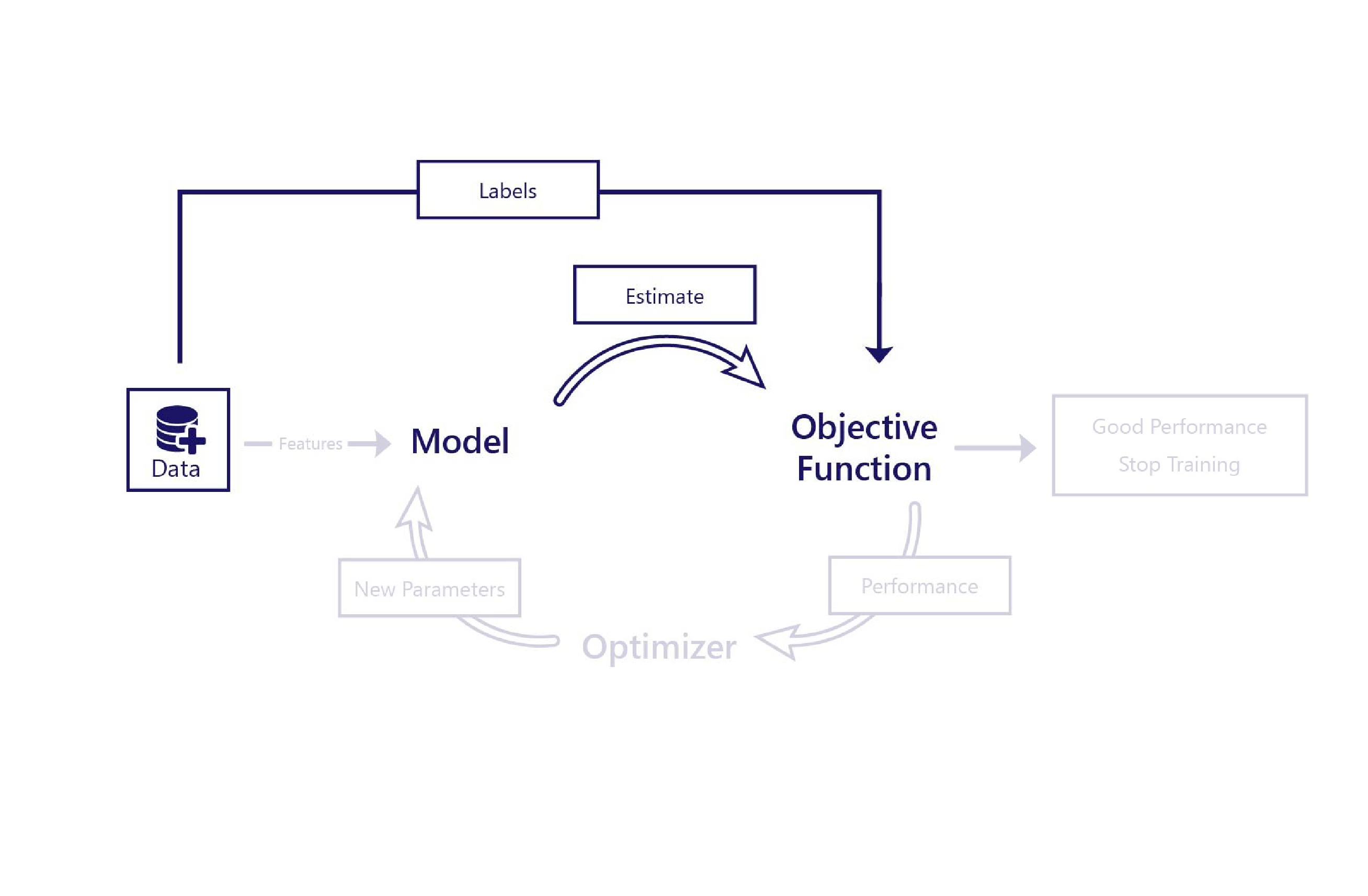

In supervised learning, a cost function is a small piece of code that calculates cost from a model's prediction and the expected label: the correct answer. For example, in our previous exercise, we calculated cost by calculating the prediction errors, squaring them, and summing them.

After the cost function calculates cost, we know whether the model is performing well or not. If it's performing well, we might choose to stop training. If not, we can pass cost information to the optimizer, which uses this information to select new parameters for the model.

During training, different cost functions can change how long training takes, or how well it works. For example, if the cost function always states that errors are small, the optimizer makes only small changes to the model. As another example, if the cost function returns large values when certain mistakes are made. Then, the optimizer makes changes to the model, so that it doesn't make these kinds of mistakes.

There isn't a one-size-fits-all cost function. Which one is best depends on what we're trying to achieve. We often need to experiment with cost functions to get a result we're happy with. In the next exercise, we'll do this experiment.