Characteristics and lifecycle of an incident

As you learned in the last unit, an incident is a service disruption that impacts your customers and end users. Incidents come in many forms, ranging from performance slowdowns that frustrate users ("slow is the new down") to system crashes that render the service or site completely unavailable for a period of time.

Characteristics of an incident

Incidents are usually unexpected and seem to occur at the worst possible time (such as 2:00 a.m., or when you're deeply immersed in an important project). This is why incidents are commonly feared and avoided, even to the point where people sometimes downplay the significance of an incident. Internal pressure is sometimes so great in an organization there is a temptation to mislabel or fail to report a disruption for fear of reprimand.

At the very least, incidents create unplanned work, and because you spend most of your time doing planned work with a good idea of what you're supposed to be doing, you probably think of incidents as bad things. However, there's another way to look at it: incidents are really investments* in providing the value you're trying to deliver to end users. Whatever the cause of the incident or the extent of the impact, all incidents have one thing in common: they can provide valuable learning experiences.

You should view incidents as the pulse of your systems. They tell you more about the system than you previously understood, and that knowledge is a good thing. When you have a strong foundation of monitoring and know more about what's going on in your system, it will inevitably generate more alerts and incidents and opportunities to respond. At the very least, incidents tell you what's going on, and thus increase your operational awareness. In a previous module on monitoring, we suggested this was an important precursor to reliability work.

Lifecycle of an incident

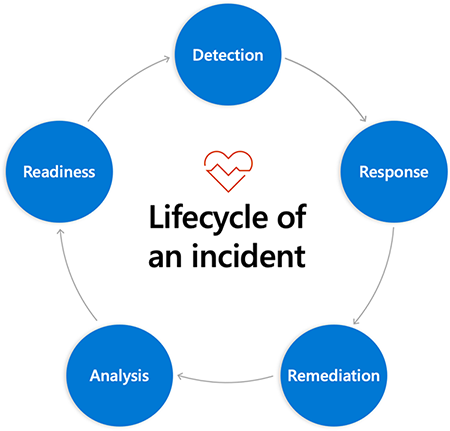

If you want to elevate your incident response team's status to "elite/high performer," you must look beyond the idea of a service disruption or incident as a simple linear timeline and approach it from a cyclic perspective.

You can separate the lifecycle of an incident into distinct phases that logically follow one after the other in a cycle that returns back to the beginning. Each time you go around this cycle (and you'll do so numerous times), if you handle it correctly, it's possible to return to the beginning with greater insight into your systems. With some intentional work, you can also be better prepared to respond quickly and effectively the next time an incident occurs.

Phases of an incident

The individual phases of the incident response process look a little different depending on the model you use. For purposes of this module, there are five phases that you go through in responding to an incident:

- Detection: This phase is where the monitoring knowledge from a previous module in this learning path comes into play. Your monitoring tools collect the information from logs, analyze that information according to the customer-centric objectives you've configured, and send you actionable alerts to let you know that human intervention is needed.

- Response: This phase is what happens after you and your team receive that alert. We'll dive into this phase in detail in this module, so there will be plenty more to say about this idea in just a moment.

- Remediation: This phase is where you restore the systems to normal functionality. How you do that depends on the cause of the service disruption. Getting the service back up and running and available to your customers is your top priority. However, your job doesn't stop once that's done.

- Analysis: To obtain lasting value from incidents, you need to learn from them. This phase is the process of gathering the information on just what happened and when during the incident and seeing what you can learn from it by asking the right questions. There's an entire module on Learning from Failure that addresses this phase.

- Readiness: You should incorporate the lessons learned in the analysis phase into your operations practice. If there are action items that would help prevent a similar outage in the future, they would also be part of this phase.

Before you create an incident response plan, you need to understand the characteristics and value of incidents and be familiar with the phases of the incident lifecycle. The next step is to ensure that your response strategy is built on a solid foundation.