Test automation and the delivery pipeline

You've learned about continuous deployment and delivery of software and services, but the two are actually part of a triad. DevOps practices are aimed at achieving continuous integration, deployment, and delivery.

Now, it's time to back up and discuss the first of these: integration. This is part of the development process that comes prior to deployment. DevOps recommends a development practice in which team members frequently integrate code into a shared repository containing a singular "main" or "trunk" codebase. The goal is to have everyone contributing to the code that will be shipped vs. working off on their copy and only bringing everything together at the last minute.

Automated testing can then verify each team member's integration. This testing helps determine that the code is "healthy" after every change and addition made. The testing is part of what we'd call a pipeline. We'll talk about pipelines in just a moment, because this unit will focus on integrated testing and delivery pipelines.

The continuous delivery pipeline

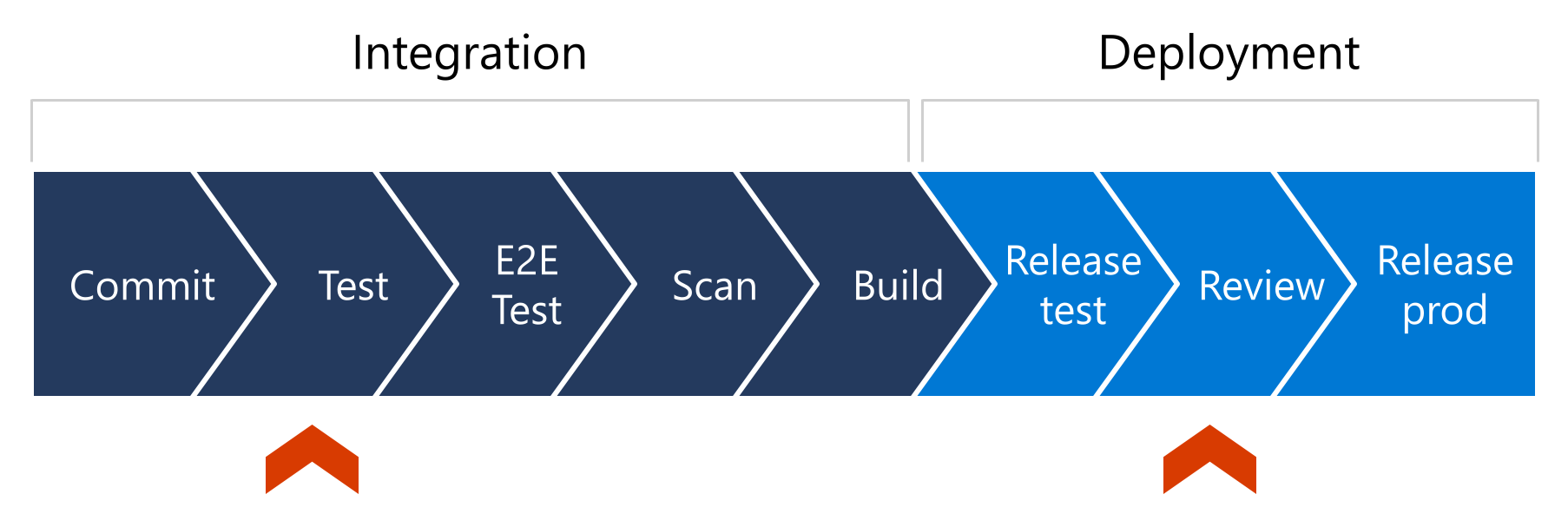

To understand automated testing's role in the continuous delivery deployment model, you need to look at where it fits into the delivery pipeline. A continuous delivery pipeline is the implementation of the set of steps code goes through as changes are made during the development process prior to deploying it to production. Here's a graphic representation of sample steps in a simplified delivery pipeline:

Let's walk through this pipeline step by step.

An instance of the pipeline starts as code or infrastructure changes are committed to a code repository, perhaps using a pull request.

Next, unit tests run—perhaps integration or end-to-end tests—and ideally, these test results are communicated back to the requesting party.

Perhaps at this point, the code in the repository is scanned for secrets, vulnerabilities, and aspects of configuration.

When everything checks out, the code is built and prepared for deployment.

Next, the code is deployed to a test environment. A human might get notified of the new deployment to give the pre-production solution a look. This human can then approve or deny the deployment for production, which starts the final part of deployment process that releases the code to production.

In this pipeline, you can note the delineation between integration and deployment. The red markers point out some logical places where you can stop the pipeline through included logic and automation, or potentially even human intervention.

Tools for continuous integration and delivery: Azure Pipelines

To use continuous integration and continuous delivery, you need the right tools. Azure Pipelines is part of Azure DevOps Services that you can use to automate building and consistently testing your code. You can also use Azure Pipelines to deploy the code to Azure services, virtual machines, and other targets both in the cloud and on premises.

The input to a pipeline (our code or configurations) resides in a version-control system such as GitHub or another Git provider.

Azure Pipelines run on a piece of compute, like a virtual machine or a container, offers build agents running Windows, Linux, and macOS. It also offers integration with testing, security, and code quality plug-ins. Finally, it’s easily extensible, so you can bring your own automation into Azure Pipelines.

Pipelines are defined using YAML syntax or via the Classic user interface in the Azure portal. When you use a YAML file, you can store that file alongside your code. Pipelines also provide templates that you can use to easily create pipelines; for example, a pipeline that builds a Docker image or a Node.js project. You can also reuse an existing YAML file.

Whether you use a YAML file or the Classic interface, here are the basic steps:

- Configure Azure Pipelines to use your Git repository.

- Define your build, either by editing the azure-pipelines.yml file or by using the Classic editor.

- Push your code to your version-control repository. This action triggers the pipeline to build and test your code.

Once the code has been updated, built, and tested, you can deploy it to whatever target you want.

There are some features (such as running container jobs) that are only available when using YAML, and others (such as task groups) that are only available using the Classic interface.

Azure Pipeline construction

Pipelines are structured into:

Jobs: A job is a grouping of tasks or steps that runs on a single build agent. A job is the smallest component of work that you can schedule to run. All of the steps in a job run sequentially. Those steps can be any sort of action you desire, including building/compiling software, preparing sample data for testing, running specific tests, and so on.

Stages: A stage is a logical grouping of related jobs.

Every pipeline has at least one stage. Use multiple stages to organize the pipeline into major divisions and mark the points in your pipeline where you can pause and perform checks.

Pipelines can be as simple or as complex as desired. There are excellent tutorials on pipeline construction and use in the Build applications with Azure DevOps learning path.

Environment traceability

There's one other aspect of pipelines related to reliability worth mentioning. You can construct your pipelines in such a way that it's possible to correlate what is running in production with a specific build instance. Ideally, we should be able trace a build back to a specific PR or code change. This can be tremendously useful, either during an incident or afterwards during the post-incident review when you're trying to identify which change contributed to an issue. Some CI/CD systems (like Azure Pipelines) make it easy to do this, while others require you manually construct a pipeline that propagates some sort of "build ID" through all of the stages.