How to use entanglement to send information?

In the previous units, you learned that quantum entanglement can be an excellent resource for quantum communication. In this unit, you'll see one of the most famous applications of entanglement: the quantum teleportation protocol.

In teleportation, entanglement is used to transfer the state of a qubit from one location to another. The state of the qubit is transferred to another qubit, but the qubit itself is not physically moved. This is an important thing to remember! The information of the state of the qubit is transferred to another qubit which is used as a vessel to write the information of the message qubit on.

The teleportation protocol uses a combination of entanglement and classical communication. The classical communication is important because the teleportation protocol requires the sender to communicate the results of their measurements to the receiver. This means that teleportation can't send information faster than the speed of light. The classical communication between the sender and the receiver is limited by the speed of light.

Let's review the protocol of quantum teleportation.

The protocol of quantum teleportation

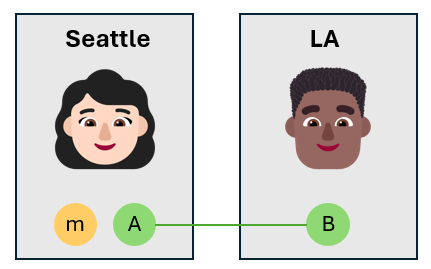

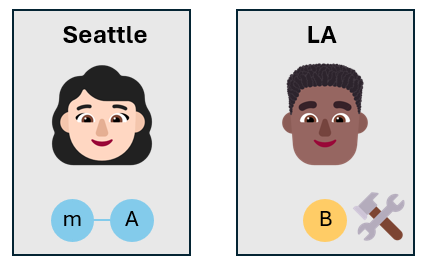

Alice and Bob work together in the same company. Alice is based in Seattle, and Bob is based in Los Angeles. They are working on a project that requires them to share quantum information. They decide to use quantum teleportation to send quantum information between them.

Initial setup

Alice and Bob each have a qubit that is part of an entangled pair that was previously prepared. The entangled pair is a Bell state, which is the state

$$\ket{\phi}=\frac1{\sqrt2}(\ket{0_A 0_B} + \ket{1_A 1_B})$$

Alice has an extra qubit – called the “message qubit” – and wants to send this qubit to Bob. The message qubit is in an unknown state that Alice wants to teleport to Bob. The state of the message qubit is

$$\ket{m}=\alpha \ket{0}_m + \beta \ket{1}_m,$$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex numbers.

The global state of Alice and Bob's three qubits is

$$\ket{\text{Global}} = (\alpha\ket{0}_m + \beta\ket{1}_m) \otimes \frac1{\sqrt2}(\ket{0_A 0_B}+ \ket{1_A 1_B}) $$

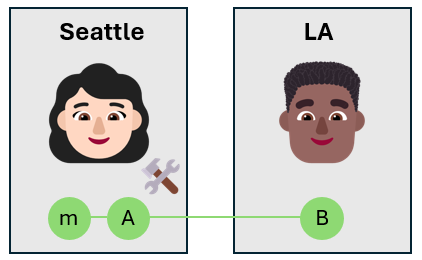

Alice entangles the message qubit with her own qubit

Alice takes the message qubit and entangles it with her own qubit $A$ using a CNOT gate. The message qubit is the control qubit, and Alice's qubit is the target qubit. This creates a three-qubit entangled state.

The message qubit is in the unknown state $\alpha \ket{0}_m + \beta \ket{1}_m$, so after applying the CNOT gate, Alice's qubits are in a superposition of the four Bell states. The global state of the three qubits is

$$ \ket{\text{Global}} = \frac1{2} \ket{\phi^+}_\text{mA} (\alpha\ket{0}_B + \beta\ket{1}_B) + $$

$$ + \frac1{2} \ket{\phi^-}_\text{mA} (\alpha\ket{0}_B - \beta\ket{1}_B) +$$

$$ + \frac1{2} \ket{\psi^+}_\text{mA}(\alpha\ket{1}_B + \beta\ket{0}_B) + $$

$$ + \frac1{2} \ket{\psi^-}_\text{mA} (\alpha\ket{1}_B- \beta\ket{0}_B)$$

The global state of Alice and Bob's qubits is a superposition of four possible states.

Tip

A good exercise is to verify that the global state of the three qubits is the one given above. You can do this by applying the CNOT gate to the message qubit and Alice's qubit, and then expanding the state of the three qubits.

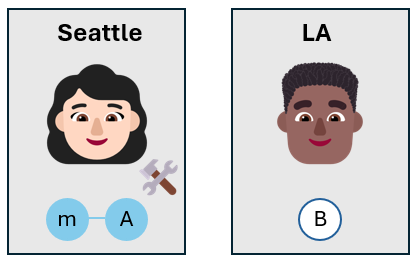

Alice measures the qubits

Alice then measures the message qubit and her own qubit. She doesn't measures the qubits in the $Z$-basis as usual, but she chooses the Bell basis. The Bell basis consists of the four Bell states, $\lbrace \ket{\phi^+}, \ket{\phi^-}, \ket{\psi^+}, \ket{\psi^-} \rbrace$.

By measuring the message qubit and her own qubit in the Bell basis, Alice projects her qubits into one of the four Bell states. Because the three qubits are entangled, the measurement results are correlated. When Alice measures her qubits, Bob's qubit is also projected into the correlated state.

For example, if Alice measures her qubits and observes the state $\ket{\phi^-}$, then Bob's qubit is projected into the state $\alpha\ket{0}_B - \beta\ket{1}_B$.

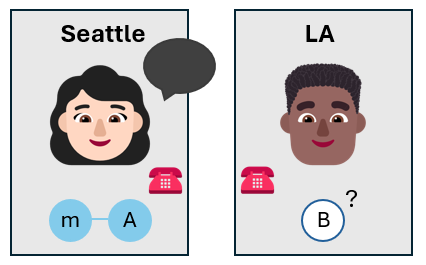

Alice calls Bob

Alice calls Bob and tells him the results of her measurements. She uses a classical communication channel, like a phone call, or a text message.

Bob now knows the state of his own qubit, without having to measure it. The state of Bob's qubit might not be the same as the state of the message qubit that Alice wanted to teleport, but it's close to it.

Bob applies a quantum operation

Next, Bob can recover the original state of the message qubit by applying a specific quantum operation to his qubit. The operation Bob performs depends on what Alice told him by phone.

The operation he executes can be a Pauli $X$ gate, a Pauli $Z$ gate, both, or none.

For example, if the result of Alice's measurement is $\ket{\phi^-}$, Bob knows that his qubit is in the state $(\alpha \ket{0}_B - \beta \ket{1}_B)$. He only needs to apply a Pauli Z gate to recover the original state of the message qubit.

| Alice measures | Bob applies |

|---|---|

| $\ket{\phi^+}$ | No operation |

| $\ket{\phi^-}$ | Pauli Z gate |

| $\ket{\psi^+}$ | Pauli X gate |

| $\ket{\psi^-}$ | Pauli X gate followed by Pauli Z gate |

This final operation effectively teleports the state of the message qubit onto Bob’s qubit. Mission accomplished!

Important

Applying an operation to a qubit isn't the same as measuring it. When Bob applies the operation, he doesn't measure his qubit. He applies a quantum operation that changes the state of the qubit, but doesn't collapse it.

In the next unit, you'll implement the quantum teleportation protocol in a Q# program.