Use a viewmodel

After learning about the components that make up the MVVM pattern, you probably found that the model and view were easy to define. Let's explore how to use the viewmodel, to better define its role in the pattern.

Expose properties to the user interface

As in the previous example, viewmodels usually rely on models for most of their data and any business logic. But it's the viewmodel that formats, converts, and enriches the data in whatever way the current view requires.

Format by using a viewmodel

You already saw an example of formatting with vacation time. Date formatting, character encoding, and serialization are all examples of how the viewmodel might format data from the model.

Convert by using a viewmodel

Often, the model provides information in indirect ways. But the viewmodel can fix that. For example, suppose you want to show on screen whether an employee is a supervisor. But our Employee model doesn't tell us that directly. Instead you have to infer this fact based on whether the person has others reporting to them. Assume that the model has this property:

public IList<Employee> DirectReports

{

get

{

...

}

}

If the list is empty, you can infer that this Employee isn't a supervisor. In this case, EmployeeViewModel includes the property IsSupervisor that provides that logic:

public bool IsSupervisor => _model.DirectReports.Any();

Enrich by using a viewmodel

Sometimes a model might only provide an ID for related data. Or you might need to go to several model classes to correlate the data required for a single screen. The viewmodel provides an ideal place to perform these tasks as well. Suppose you want to show all the projects that an employee is currently managing. This data isn't part of the Employee model class. It can be accessed by looking at the CompanyProjects model class. Our EmployeeViewModel, as always, exposes its work as a public property:

public IEnumerable<string> ActiveProjects => CompanyProjects.All

.Where(p => p.Owner == _model.Id && p.IsActive)

.Select(p => p.Name);

Use pass-through properties with a viewmodel

Frequently a viewmodel needs exactly the property that the model provides. For those properties, the viewmodel just passes the data through:

public string Name

{

get => _model.Name;

set => _model.Name = value;

}

Set the scope for the viewmodel

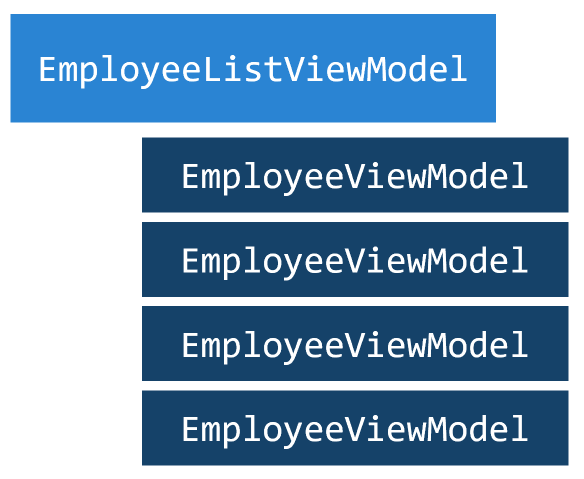

You can use a viewmodel at any level where there's a view. A page usually has a viewmodel, but so might subviews of the page. One common reason for nested viewmodels is when the page displays a ListView on the page. The list has a viewmodel that represents the collection, such as EmployeeListViewModel. Each element in the list is an EmployeeViewModel.

It's also common to have a top-level viewmodel that holds data and state for the entire application but isn't associated with any particular page. Such a viewmodel is commonly used for maintaining the "active" item. Consider the ListView example just described. When the user selects an employee row, that employee represents the current item. If the user navigates to a detail page or selects a toolbar button while that row is selected, the action or display should be for that employee. An elegant way of handling this scenario is to have the ListView.SelectItem data-bound to a property that the toolbar or detail page can also access. Putting that property on a central viewmodel works well.

Identify when to reuse viewmodels with views

How you define the relationship between the viewmodel and model and between the viewmodel and view is dictated more by app requirements than by rules. The viewmodel's purpose is to provide to the view the structure and data that it needs. That should guide decisions about "how big" to scope a viewmodel.

Viewmodels often closely reflect the structure of a model class, and they have a one-to-one relationship with that class. You saw an example earlier with the EmployeeViewModel that wrapped and augmented a single Employee instance. But it isn't always a one-to-one relationship. If the viewmodel is designed to provide what the view needs, you might instead end up with something like HRDashboardViewModel to give an overview of an HR department, which has no explicit relationship with any model but can use data from any model class.

Similarly, you might find that viewmodels and views often have a one-to-one relationship. But this also isn't necessarily the case. Let's again think about a ListView that shows a row for each employee. When you select one of the rows, you go to an employee-detail page.

The list page has its viewmodel with a collection. As suggested earlier, that collection could be a collection of EmployeeViewModel objects. And when the user selects a row, the EmployeeViewModel instance could be passed to the EmployeeDetailPage. And the detail page could use that EmployeeViewModel as its BindingContext.

This scenario might be an excellent opportunity for viewmodel reuse. But keep in mind that viewmodels are intended to provide what the view needs. In some cases, you might want separate viewmodels, even if they're all based on the same model class. In this example, the ListView rows are likely to need much less information than the full detail page. If retrieving the data the detail page needs adds a lot if overhead, you might want to have both EmployeeListRowViewModel and EmployeeDetailViewModel models that service these respective views.

Viewmodel object model

Using a base class that implements INotifyPropertyChanged means that you don't need to reimplement the interface on every viewmodel. Consider the HR application as described in the previous part of this training module. The EmployeeViewModel class implemented the INotifyPropertyChanged interface and provided a helper method named OnPropertyChanged to raise the PropertyChanged event. Other viewmodels in the project, like ones that describe resources assigned to an employee, would also require INotifyPropertyChanged to fully integrate with a view.

The MVVM Toolkit library, part of the .NET Community Toolkit, is a collection of standard, self-contained, lightweight types that provide a starting implementation for building modern apps using the MVVM pattern.

Instead of writing your own viewmodel base class, you inherit from the toolkit's ObservableObject class, which provides everything you need for a viewmodel base class. The EmployeeViewModel can be simplified from:

using System.ComponentModel;

public class EmployeeViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler? PropertyChanged;

private Employee _model;

public string Name

{

get {...}

set

{

_model.Name = value;

OnPropertyChanged(nameof(Name))

}

}

protected void OnPropertyChanged(string propertyName) =>

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

To the following code:

using Microsoft.Toolkit.Mvvm.ComponentModel;

public class EmployeeViewModel : ObservableObject

{

private string _name;

public string Name

{

get => _name;

set => SetProperty(ref _name, value);

}

}

The MVVM Toolkit is distributed through the CommunityToolkit.Mvvm NuGet package.