Summary of Chapter 8. Code and XAML in harmony

Note

This book was published in the spring of 2016, and has not been updated since then. There is much in the book that remains valuable, but some of the material is outdated, and some topics are no longer entirely correct or complete.

This chapter explores XAML more deeply, and particularly how code and XAML interact.

Passing arguments

In the general case, a class instantiated in XAML must have a public parameterless constructor; the resultant object is initialized through property settings. However, there are two other ways that objects can be instantiated and initialized.

Although these are general-purpose techniques, they are mostly used in connection with MVVM View Models.

Constructors with arguments

The ParameteredConstructorDemo sample demonstrates how to use the x:Arguments tag to specify constructor arguments. These arguments must be delimited by element tags indicating the type of the argument. For the basic .NET data types, the following tags are available:

x:Objectx:Booleanx:Bytex:Int16x:Int32x:Int64x:Singlex:Doublex:Decimalx:Charx:Stringx:TimeSpanx:Arrayx:DateTime

Can I call methods from XAML?

The FactoryMethodDemo sample demonstrates how to use the x:FactoryMethod element to specify a factory method that is invoked to create an object. Such a factory method must be public and static, and it must create an object of the type in which it is defined. (For example the Color.FromRgb method qualifies because it is public and static and returns a value of type Color.) The arguments to the factory method are specified within x:Arguments tags.

The x:Name attribute

The x:Name attribute allows an object instantiated in XAML to be given a name. The rules for these names are the same as for C# variable names. Following the return of the InitializeComponent call in the constructor, the code-behind file can refer to these names to access the corresponding XAML element. The names are actually converted by the XAML parser into private fields in the generated partial class.

The XamlClock sample demonstrates the use of x:Name to allow the code-behind file to keep two Label elements defined in XAML updated with the current date and time.

The same name cannot be used for multiple elements on the same page. This is a particular problem if you use OnPlatform to create parallel named objects for each platform. The PlatformSpecificLabele sample demonstrates a better way to do something like that.

Custom XAML-based views

There are several ways to avoid repetition of markup in XAML. One common technique is to create a new XAML-based class that derives from ContentView. This technique is demonstrated in the ColorViewList sample. The ColorView class derives from ContentView to display a particular color and its name, while the ColorViewListPage class derives from ContentPage as usual and explicitly creates 17 instances of ColorView.

Accessing the ColorView class in XAML requires another XML namespace declaration, commonly named local for classes in the same assembly.

Events and handlers

Events can be assigned to event handlers in XAML, but the event handler itself must be implemented in the code-behind file. The XamlKeypad demonstrates how to build a keypad user interface in XAML and how to implement the Clicked handlers in the code-behind file.

Tap gestures

Any View object can obtain touch input and generate events from that input. The View class defines a GestureRecognizers collection property that can contain one or more instances of classes that derive from GestureRecognizer.

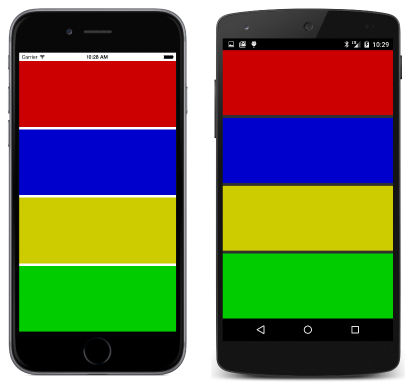

The TapGestureRecognizer generates Tapped events. The MonkeyTap program demonstrates how to attach TapGestureRecognizer objects to four BoxView elements to create an imitation game:

But the MonkeyTap program really needs sound. (See the next chapter.)