Data domains

Data mesh is fundamentally based on decentralization and the distribution of responsibility to domains. If you truly understand a part of the business, you're best positioned to manage the associated data and ensure its accuracy. This is the principle of domain-oriented data ownership.

To promote domain-oriented data ownership, you need to first decompose your data architecture. The data mesh founder, Zhamak Dehghani, promotes the Domain-Driven Design (DDD) approach to software development as a useful method to help you identify your data domains.

The difficulty with using DDD for data management is that DDD's original use case was modeling complex systems in a software development context. It wasn't originally created to model enterprise data, and for data management practitioners, its method can be abstract and technical. There's often a lack of understanding of DDD. Practitioners find its conceptual notions too difficult to grasp or try to project examples from software architecture or object-oriented programming onto their data landscape. This article provides you with pragmatic guidance and clear vocabulary so you can understand and use DDD.

Domain-driven design

Introduced by Eric Evans, Domain-Driven Design is a method for supporting software development that helps describe complex systems for larger organizations. DDD is popular because many of its high-level practices impact modern software and application development approaches, such as microservices.

DDD differentiates between bounded contexts, domains, and subdomains. Domains are problem spaces you want to address. They're areas where knowledge, behavior, laws, and activities come together. You see semantic coupling in domains, behavioral dependencies between components or services. Another aspect of domains is communication. Team members must use a language the whole team shares so everyone can work efficiently. This shared language is called the ubiquitous language or domain language.

Domains are decomposed into subdomains to better manage complexity. A common example of this is decomposing a domain into subdomains that each correspond to one specific business problem, as shown in Operationalize data mesh for AI/ML.

Not all subdomains are the same. You can, for example, classify domains as core, generic, or supporting. Core subdomains are the most important. They're the secret sauce, the ingredients, that make an organization unique. Generic subdomains are nonspecific and typically easy to solve with off-the-shelf products. Supporting subdomains don't offer a competitive advantage but are necessary to keep an organization running and aren't complex.

Bounded contexts are logical (context) boundaries. They focus on the solution space: the design of systems and applications. It's an area where the alignment of focus on the solution space makes sense. Within DDD, this can include code, database designs, and so on. Between the domains and bounded contexts, there can be alignment, but there's no hard rule binding the two together. Bounded contexts are technical by nature and can span multiple domains and subdomains.

Domain modeling recommendations

If you adopt data mesh as a concept for data democratization and implement the principle of domain-oriented data ownership to increase flexibility, how does this work in practice? What might a transition from enterprise data modeling to domain-driven design modeling look like? What lessons can you take from DDD for data management?

Make a functional business decomposition of your problem spaces

Before allowing your teams to operate their data end-to-end, look at the scope and understand the problem spaces you're trying to address. It's important to do this exercise first before you jump into the details of a technical implementation. When you set logical boundaries between these problem spaces, responsibilities become clearer and can be better managed.

Look at your business architecture when grouping your problem spaces. Within business architecture, there are business capabilities: abilities or capacities that a business possesses or exchanges to achieve a specific purpose or outcome. This abstraction packs data, processes, organization, and technology into a particular context, in alignment with the strategic business goals and objectives of your organization. A business capability map shows which functional areas appear to be necessary to fulfill your mission and vision.

You can view the capability decomposition of a fictional company, Tailwind Traders, in the following model.

Tailwind Traders needs to master all functional areas listed in the Business Capability Map to be successful. Tailwind Traders must be able to sell tickets as part of Online or Offline Tickets Management Systems, for example, or have Pilots available to fly planes as part of a Pilot Management Program. The company can outsource some activities while keeping others as the core of its business.

What you observe in practice is that most of your people are organized around business capabilities. People working on the same business capabilities share the same vocabulary. The same is true of your applications and processes, which are typically well-aligned and tightly connected based on the cohesion of activities they support.

Business capability mapping is a great starting point, but your story doesn't end here.

Map business capabilities to applications and data

To better manage your enterprise architecture, align your business capabilities, bounded contexts, and applications. It's important to follow some ground rules as you do so.

Business capabilities must stay on the business level and remain abstract. They represent what your organization does and target your problem spaces. When you implement a business capability, a realization (capability instance) for a specific context is created. Multiple applications and components work together within such boundaries in your solution space to deliver specific business value.

Applications and components aligned with a particular business capability stay decoupled from applications that are aligned with other business capabilities because they address different business concerns. Bounded contexts are derived from and exclusively mapped to business capabilities. They represent the boundary of a business capability implementation, and they behave like a domain.

If business capabilities change, bounded contexts change. You preferably expect full alignment between domains and corresponding bounded contexts, but as you learn in later sections, reality sometimes differs from the ideal.

If we project capability mapping to Tailwind Traders, bounded context boundaries and domain implementations might look similar to the following diagram.

In this diagram, Customer Management is built upon subject matter expertise and therefore knows best what data to serve to other domains. Customer Management's inner architecture is decoupled, so all application components within these boundaries can directly communicate using application-specific interfaces and data models.

Data products and clear interoperability standards are used to formalize data distribution to other domains. In this approach, all data products also align with the domain and inherit the ubiquitous language, which is a constructed, formalized language agreed upon by stakeholders and designers from the same domain, to serve the needs of that domain.

Extra domains from multiple capability realizations

It's important to acknowledge when working with business capability maps that some business capabilities can be instantiated multiple times.

As an example, Tailwind Traders might have multiple localized realizations (or implementations) of "baggage handling and lost items." Assume one line of their business operates only in Asia. In this context, "baggage handling and lost items" is a capability that is fulfilled for Asia-related airplanes. A different line of business might target the European market, and in this context, another "baggage handling and lost items" capability is used. This scenario of multiple instances can lead to multiple localized implementations using different technology services and disjointed teams to operate those services.

The relationship of business capability and capability instances (realizations) is one-to-many. Because of this, you end up with extra (sub-) domains.

Find shared capabilities and watch out for shared data

How you handle shared business capabilities is important. You typically implement shared capabilities centrally, as service models, and provide them to different lines of business. "Customer Management" can be an example of this kind of capability. In our Tailwind Traders example, both the Asian and European lines of business use the same administration for their clients.

But how can you project domain data ownership on a shared capability? Multiple business representatives likely take accountability for customers within the same shared administration.

There's an application domain and a data domain. Your domain and bounded context don't perfectly align from a data product viewpoint. You could conversely argue that there's still a single data concern from a business capability viewpoint.

For shared capabilities like complex vendor packages, SaaS solutions, and legacy systems, be consistent in your domain data ownership approach. You can segregate data ownership via data products, which might require application improvements. In our Tailwind Traders "Customer Management" example, different pipelines from the application domain might generate multiple data products: one data product for all Asia-related customers, and one for all Europe-related customers. In this situation, multiple data domains originate from the same application domain.

You can also ask your application domains to create a single data product that encapsulates metadata for distinguishing data ownership within itself. You could, for example, reserve a column name for ownership, mapping each row to a single specific data domain.

Identify monoliths offering multiple business capabilities

Pay attention also to applications that cater to multiple business capabilities, which are often seen in large and traditional enterprises. In our example scenario, Tailwind Traders use a complex software package to facilitate both "cost management" and "assets and financing." These shared applications are monoliths that provide as many features as possible, making them large and complex. In such a situation, the application domain should be larger. The same thing applies to shared ownership, in which several data domains reside in an application domain.

Design patterns for source-aligned, redelivery, and consumer-aligned domains

When you map your domains, you can choose a pattern based on the creation, consumption, or redelivery of your data. For your architecture, you can design templates that support your domains based on the domain's specific characteristics.

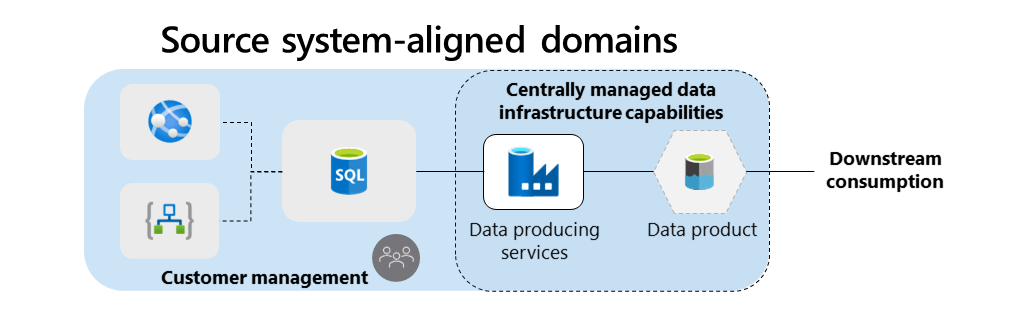

Source system-aligned domains

Source system-aligned domains are aligned with source systems where data originates. These systems are typically transactional or operational.

Your goal is to capture data directly from these golden source systems. Read-optimized data products from your providing domains for intensive data consumption. Facilitate these domains using standardized services for data transformation and sharing.

These services, which include preconfigured container structures, enable your source-oriented domain teams to publish data more easily. It's the path of least resistance with minimal disruption and cost.

Consumer-aligned domains

Consumer-aligned domains are the opposite of source-aligned domains. They're aligned with specific end-user use cases that require data from other domains. Customer-aligned domains consume and transform data to fit the use cases of your organization.

Consider offering shared data services for data transformation and consumption to cater to these consuming needs. You could offer domain-agnostic data infrastructure capabilities, for example, to handle data pipelines, storage infrastructure, streaming services, analytical processing, and so on.

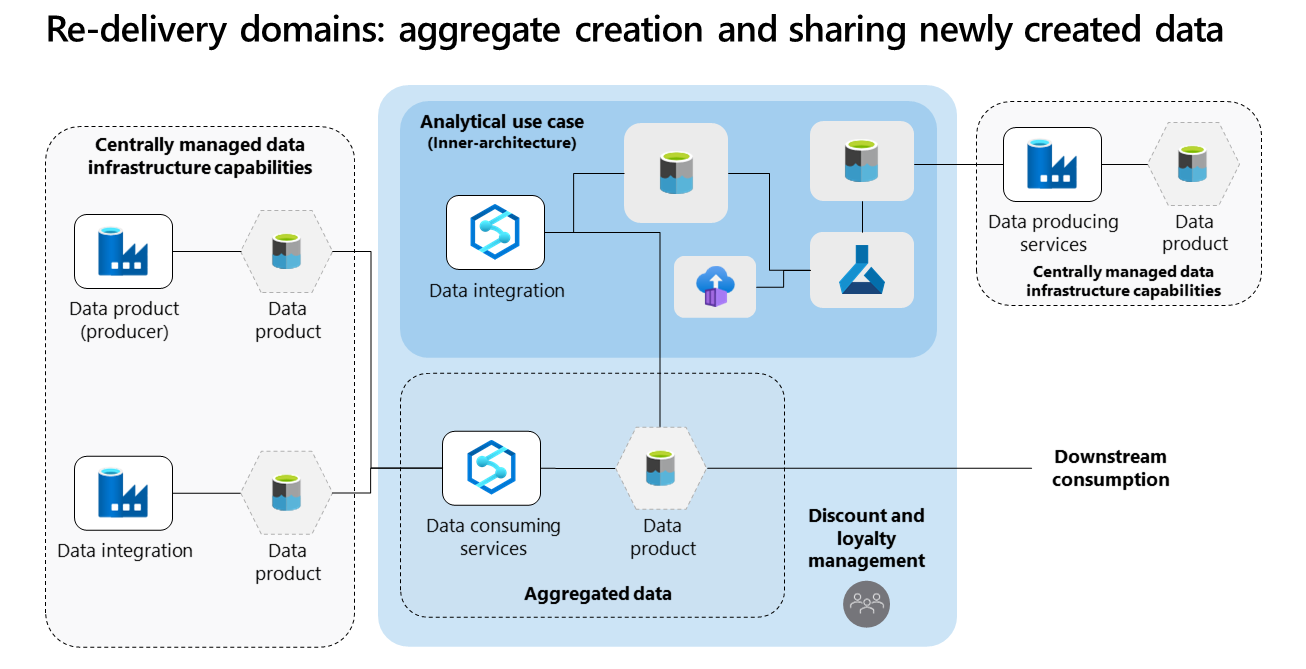

Redelivery domains

The reusability of data is a different and more difficult scenario. For example, if downstream consumers are interested in a combination of data from different domains, you can create data products that aggregate data or combine high-level data required by many domains. This allows you to avoid repetitive work.

Don't create strong dependencies between your data products and analytical use cases. Strive for flexibility and loose coupling instead. The following model demonstrates how you can achieve flexibility. A domain takes ownership of both data products and analytical use cases and has designed separate processes for data product creation and data usage.

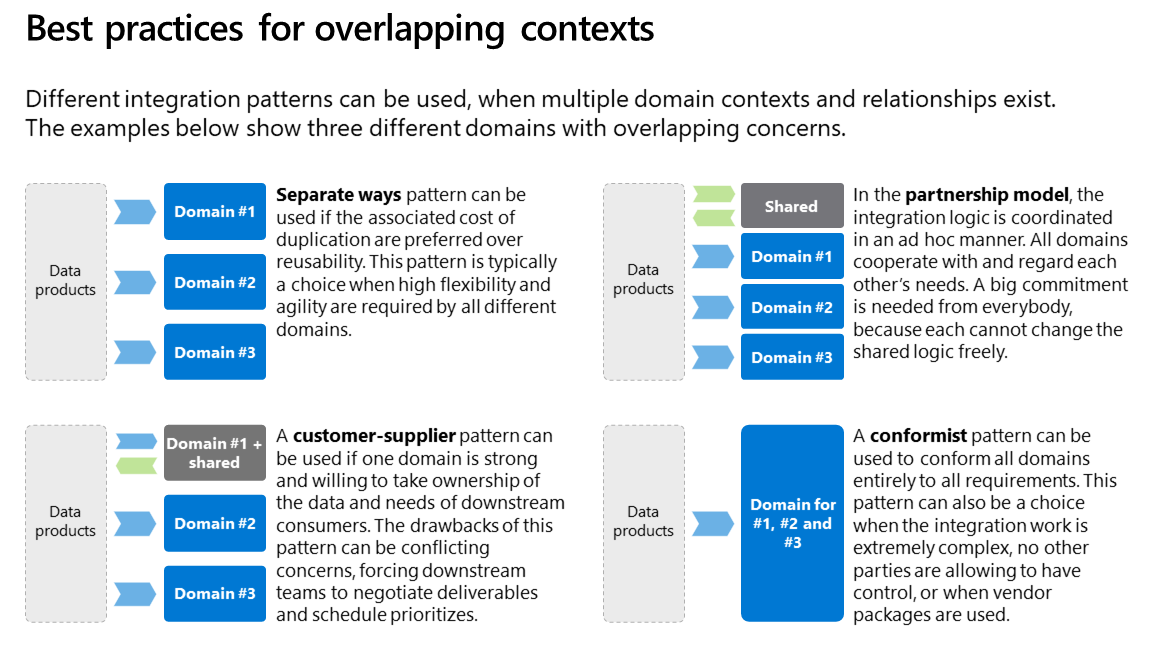

Define overlapping domain patterns

Domain modeling often gets complicated when data or business logic is shared across domains. In large-scale organizations, domains often rely on data from other domains. It can be helpful to have generic domains that provide integration logic in a way that allows other subdomains to standardize and benefit from it. Keep your shared model between subdomains small and always aligned with the ubiquitous language.

For overlapping data requirements, you can use different patterns from domain-driven design. Here's a short summary of the patterns you could choose from:

- A separate ways pattern can be used if you prefer the associated cost of duplication over reusability. Reusability is sacrificed for higher flexibility and agility.

- A customer-supplier pattern can be used if one domain is strong and willing to take ownership of downstream consumers' data and needs. Drawbacks include conflicting concerns and forcing your downstream teams to negotiate deliverables and schedule priorities.

- A partnership pattern can be used when your integration logic is coordinated in an unplanned manner within a newly created domain. All teams cooperate with and regard each other's needs. Because no one can freely change the shared logic, significant commitment is needed from everyone involved.

- A conformist pattern can be used to conform all your domains to all requirements. Use this pattern when your integration work is complex, no other parties can have control, or you use vendor packages.

In all cases, your domains should adhere to your interoperability standards. A partnership domain that produces new data for other domains must expose their data products like any other domain, including taking ownership.

Domain responsibilities

Data mesh decentralizes data ownership by distributing it among domain teams. For many organizations, this means a shift from a centralized model around governance to a federated model. Domain teams are assigned tasks, such as:

- Taking ownership of data pipelines, such as ingestion, cleaning, and transforming data, to serve as many data customers' needs as possible

- Improving Data Quality, including adherence to SLAs and quality measures set by data consumers

- Encapsulating metadata or using reserved column names for fine-grain row- and column-level filtering

- Adhering to metadata management standards, including:

- Application and source system schema registration

- Metadata for improved discoverability

- Versioning information

- Linkage of data attributes and business terms

- Integrity of metadata information to allow better integration between domains

- Adhering to data interoperability standards, including protocols, data formats, and data types

- Providing lineage either by linking source systems and integration services to scanners or by manually providing lineage

- Adhering to data sharing tasks, including IAM access reviews and data contract creation

Level of granularity for decoupling

Now that you know how to recognize and facilitate data domains, you can learn to design the right level of domain granularity and rules for decoupling. Two important dimensions are in play when you decompose your architecture.

Granularity for functional domains and setting bounded contexts is one dimension. Domains conform to a particular way of working, ensuring data becomes available to all domains using shared services, taking ownership, adhering to metadata standards, and so on.

Set fine-grained boundaries where possible for data distribution. Becoming data-driven is all about making data available for intensive reuse. If you make your boundaries too loose, you force undesired couplings between many applications and lose data reusability. Strive for decoupling each time data crosses boundaries of business capabilities. Within a domain, tight coupling within the inner architecture of the domain is allowed. However, when crossing the boundaries of business capabilities, domains must stay decoupled and distribute read-optimized data products for sharing with other domains.

Granularity for technical domains and infrastructure utilization is the other important dimension. Your data landing zones enable agility for servicing data applications, which create data products. How do you create this kind of landing zone with shared infrastructure and services underneath? Functional domains are logically grouped together and are good candidates for sharing platform infrastructure. Here are some factors to consider when creating these landing zones:

- Cohesion and efficiency when working with and sharing data is a strong driver of aligning functional domains to a data landing zone. This relates to data gravity, the tendency to constantly share large data products between domains.

- Regional boundaries can result in extra data landing zones being implemented.

- Ownership, security, or legal boundaries can force domain segregation. For example, some data can't be visible to any other domains.

- Flexibility and the pace of change are important drivers. Some domains can have a high velocity of innovation, while other domains strongly value stability.

- Functional boundaries can drive teams apart. An example of this could be source-oriented and consumer-oriented boundaries. Half of your domain teams might value certain services over others.

- If you want to potentially sell or separate off your capability, you should avoid integrating tightly with shared services from other domains.

- Team size, skills, and maturity can all be important factors. Highly skilled and mature teams often prefer to operate their own services and infrastructure, while less mature teams are less likely to value the extra overhead of platform maintenance.

Before you provision many data landing zones, look at your domain decomposition and determine what functional domains are candidates for sharing underlying infrastructure.

Summary

Business capability modeling helps you to better recognize and organize your domains in a data mesh architecture. It provides a holistic view of the way data and applications deliver value to your business while at the same time helping you prioritize and focus on your data strategy and business needs. You can also use business capability modeling for more than just data. For example, if scalability is a concern, you can use this model to identify your most critical core capabilities and develop a strategy for them.

Some practitioners raise the concern that building target-state architecture by mapping everything out upfront is an intensive exercise. They instead suggest you identify your domains organically while you onboard them into your new data mesh architecture. Instead of defining your target state from the top down, you work bottom-up, exploring, experimenting, and transitioning your current state towards a target state. While this proposed approach might be quicker, it carries significant risk. You can easily be in the middle of a complex move or remodeling operation when things start to break. Working from both directions, top-down and bottom-up, and then meeting in the middle over time is a more nuanced approach.