A big data architecture is designed to handle the ingestion, processing, and analysis of data that is too large or complex for traditional database systems. The threshold at which organizations enter into the big data realm differs, depending on the capabilities of the users and their tools. For some, it can mean hundreds of gigabytes of data, while for others it means hundreds of terabytes. As tools for working with big datasets advance, so does the meaning of big data. More and more, this term relates to the value you can extract from your data sets through advanced analytics, rather than strictly the size of the data, although in these cases they tend to be quite large.

Over the years, the data landscape has changed. What you can do, or are expected to do, with data has changed. The cost of storage has fallen dramatically, while the means by which data is collected keeps growing. Some data arrives at a rapid pace, constantly demanding to be collected and observed. Other data arrives more slowly, but in very large chunks, often in the form of decades of historical data. You might be facing an advanced analytics problem, or one that requires machine learning. These are challenges that big data architectures seek to solve.

Big data solutions typically involve one or more of the following types of workload:

- Batch processing of big data sources at rest.

- Real-time processing of big data in motion.

- Interactive exploration of big data.

- Predictive analytics and machine learning.

Consider big data architectures when you need to:

- Store and process data in volumes too large for a traditional database.

- Transform unstructured data for analysis and reporting.

- Capture, process, and analyze unbounded streams of data in real time, or with low latency.

Components of a big data architecture

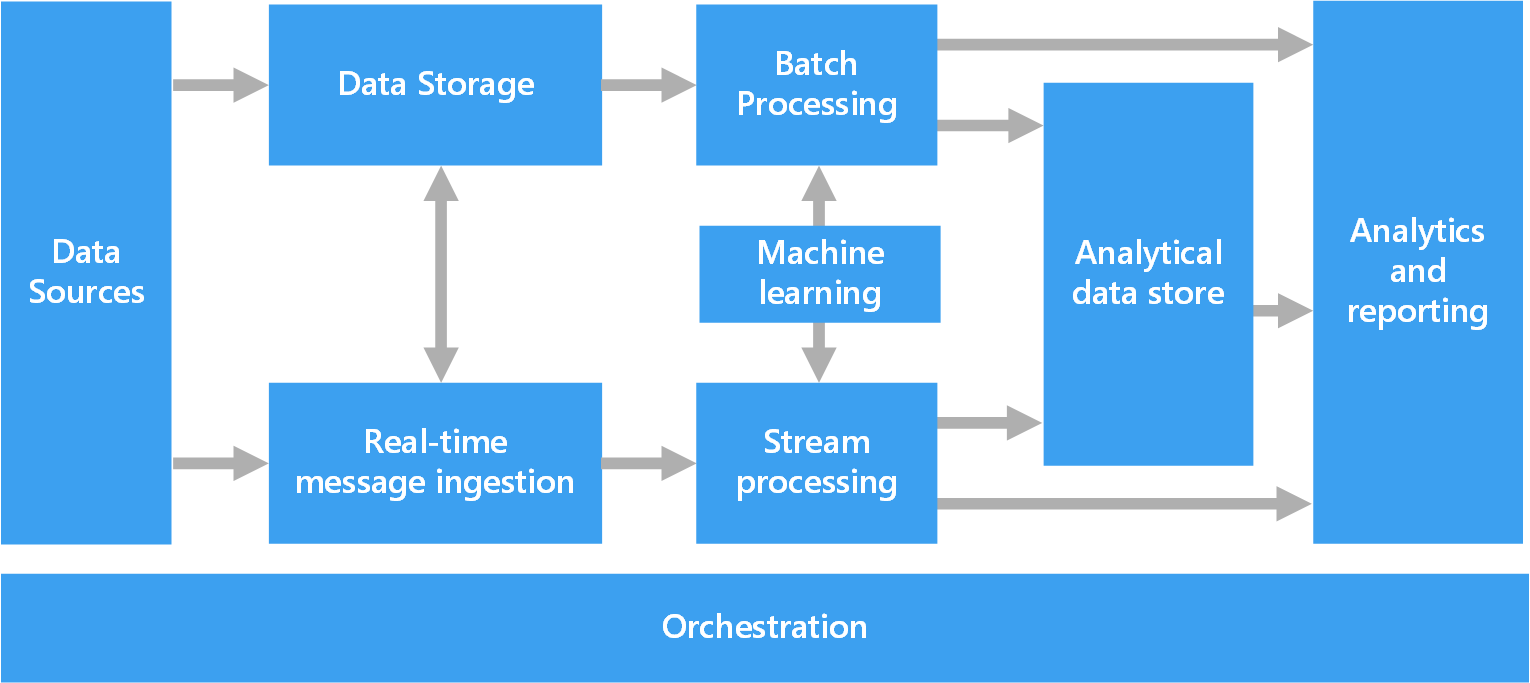

The following diagram shows the logical components that fit into a big data architecture. Individual solutions may not contain every item in this diagram.

Most big data architectures include some or all of the following components:

Data sources. All big data solutions start with one or more data sources. Examples include:

- Application data stores, such as relational databases.

- Static files produced by applications, such as web server log files.

- Real-time data sources, such as IoT devices.

Data storage. Data for batch processing operations is typically stored in a distributed file store that can hold high volumes of large files in various formats. This kind of store is often called a data lake. Options for implementing this storage include Azure Data Lake Store, blob containers in Azure Storage, or One Lake in Microsoft Fabric.

Batch processing. Because the data sets are so large, often a big data solution must process data files using long-running batch jobs to filter, aggregate, and otherwise prepare the data for analysis. Usually these jobs involve reading source files, processing them, and writing the output to new files. Options include:

- Run U-SQL jobs in Azure Data Lake Analytics

- Use Hive, Pig, or custom Map/Reduce jobs in an HDInsight Hadoop cluster

- Use Java, Scala, or Python programs in an HDInsight Spark cluster

- Use Python, Scala or SQL language in notebooks of Azure Databricks

- Use Python, Scala or SQL language in notebooks of Microsoft Fabric

Real-time message ingestion. If the solution includes real-time sources, the architecture must include a way to capture and store real-time messages for stream processing. This might be a simple data store, where incoming messages are dropped into a folder for processing. However, many solutions need a message ingestion store to act as a buffer for messages, and to support scale-out processing, reliable delivery, and other message queuing semantics. This portion of a streaming architecture is often referred to as stream buffering. Options include Azure Event Hubs, Azure IoT Hub, and Kafka.

Stream processing. After capturing real-time messages, the solution must process them by filtering, aggregating, and otherwise preparing the data for analysis. The processed stream data is then written to an output sink.

- Azure Stream Analytics provides a managed stream processing service based on perpetually running SQL queries that operate on unbounded streams.

- You can also use open source Apache streaming technologies like Spark Streaming in an HDInsight cluster or in Azure Databricks

- Azure Functions is a serverless compute service that can run event-driven code which is ideal for lightweight stream processing tasks

- Microsoft Fabric supports real-time data processing with event streams and Spark processing.

Machine learning. Reading the prepared data for analysis (from batch or stream processing), you use machine learning algorithms to build models that predict outcomes or classify data. These models can be trained on large datasets, and the resulting models are used to analyze new data and make predictions. This can be done using Azure Machine Learning, which provides tools for building, training, and deploying models. Alternatively, you can use pre-built APIs for common machine learning tasks such as vision, speech, language, and decision-making offered by Azure AI Services.

Analytical data store. Many big data solutions prepare data for analysis and then serve the processed data in a structured format that can be queried using analytical tools. The analytical data store used to serve these queries can be a Kimball-style relational data warehouse, as seen in most traditional business intelligence (BI) solutions. Alternatively, the data could be presented through a low-latency NoSQL technology such as HBase, or an interactive Hive database that provides a metadata abstraction over data files in the distributed data store.

- Azure Synapse Analytics provides a managed service for large-scale, cloud-based data warehousing.

- HDInsight supports Interactive Hive, HBase, and Spark SQL, which can also be used to serve data for analysis.

- Microsoft Fabric provides a variety of data stores, including SQL Databases, Data Warehouses, lakehouses, and eventhouses, which can be used for serving data for analysis.

- Azure offers other analytical data stores such as Azure Databricks, Azure Data Explorer, Azure SQL Database, and Azure Cosmos DB.

Analysis and reporting. The goal of most big data solutions is to provide insights into the data through analysis and reporting. To empower users to analyze the data, the architecture may include a data modeling layer, such as a multidimensional OLAP cube or tabular data model in Azure Analysis Services. It might also support self-service BI, using the modeling and visualization technologies in Microsoft Power BI or Microsoft Excel. Analysis and reporting can also take the form of interactive data exploration by data scientists or data analysts. For these scenarios, many Azure services support analytical notebooks, such as Jupyter, enabling these users to use their existing skills with Python or Microsoft R. For large-scale data exploration, you can use Microsoft R Server, either standalone or with Spark. Additionally, Microsoft Fabric offers the capability to edit data models directly within the service, adding flexibility and efficiency to the task of data modeling and analysis.

Orchestration. Most big data solutions consist of repeated data processing operations, encapsulated in workflows, that transform source data, move data between multiple sources and sinks, load the processed data into an analytical data store, or push the results straight to a report or dashboard. To automate these workflows, you can use an orchestration technology such Azure Data Factory, Microsoft Fabric, or Apache Oozie and Sqoop.

Lambda architecture

When working with very large data sets, it can take a long time to run the sort of queries that clients need. These queries can't be performed in real time, and often require algorithms such as MapReduce that operate in parallel across the entire data set. The results are then stored separately from the raw data and used for querying.

One drawback to this approach is that it introduces latency — if processing takes a few hours, a query may return results that are several hours old. Ideally, you would like to get some results in real time (perhaps with some loss of accuracy), and combine these results with the results from the batch analytics.

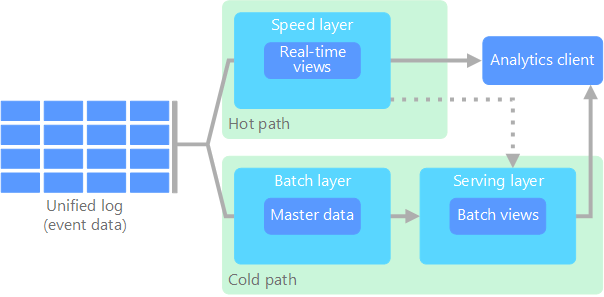

The lambda architecture, first proposed by Nathan Marz, addresses this problem by creating two paths for data flow. All data coming into the system goes through these two paths:

A batch layer (cold path) stores all of the incoming data in its raw form and performs batch processing on the data. The result of this processing is stored as a batch view.

A speed layer (hot path) analyzes data in real time. This layer is designed for low latency, at the expense of accuracy.

The batch layer feeds into a serving layer that indexes the batch view for efficient querying. The speed layer updates the serving layer with incremental updates based on the most recent data.

Data that flows into the hot path is constrained by latency requirements imposed by the speed layer, so that it can be processed as quickly as possible. Often, this requires a tradeoff of some level of accuracy in favor of data that is ready as quickly as possible. For example, consider an IoT scenario where a large number of temperature sensors are sending telemetry data. The speed layer may be used to process a sliding time window of the incoming data.

Data flowing into the cold path, on the other hand, is not subject to the same low latency requirements. This allows for high accuracy computation across large data sets, which can be very time intensive.

Eventually, the hot and cold paths converge at the analytics client application. If the client needs to display timely, yet potentially less accurate data in real time, it will acquire its result from the hot path. Otherwise, it will select results from the cold path to display less timely but more accurate data. In other words, the hot path has data for a relatively small window of time, after which the results can be updated with more accurate data from the cold path.

The raw data stored at the batch layer is immutable. Incoming data is always appended to the existing data, and the previous data is never overwritten. Any changes to the value of a particular datum are stored as a new timestamped event record. This allows for recomputation at any point in time across the history of the data collected. The ability to recompute the batch view from the original raw data is important, because it allows for new views to be created as the system evolves.

Kappa architecture

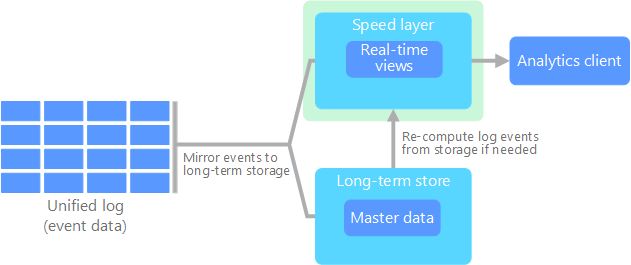

A drawback to the lambda architecture is its complexity. Processing logic appears in two different places — the cold and hot paths — using different frameworks. This leads to duplicate computation logic and the complexity of managing the architecture for both paths.

The kappa architecture was proposed by Jay Kreps as an alternative to the lambda architecture. It has the same basic goals as the lambda architecture, but with an important distinction: All data flows through a single path, using a stream processing system.

There are some similarities to the lambda architecture's batch layer, in that the event data is immutable and all of it is collected, instead of a subset. The data is ingested as a stream of events into a distributed and fault tolerant unified log. These events are ordered, and the current state of an event is changed only by a new event being appended. Similar to a lambda architecture's speed layer, all event processing is performed on the input stream and persisted as a real-time view.

If you need to recompute the entire data set (equivalent to what the batch layer does in lambda), you simply replay the stream, typically using parallelism to complete the computation in a timely fashion.

Lakehouse architecture

A data lake is a centralized data repository that allows you to store all your structured (like database tables), semi-structured data (like XML files), and unstructured data (like images and audio files) in its raw, original format, without requiring any predefined schema. The data lake is designed to handle large volumes of data, making it suitable for big data processing and analytics. By using low-cost storage solutions, data lakes provide a cost-effective way to store large amounts of data.

A data warehouse is a centralized repository that stores structured and semi-structured data for reporting, analysis, and business intelligence purposes. Data warehouses are essential for organizations to make informed decisions by providing a consistent and comprehensive view of their data.

The Lakehouse architecture combines the best elements of data lakes and data warehouses. The pattern aims to provide a unified platform that supports both structured and unstructured data, enabling efficient data management and analytics. These systems typically utilize low-cost cloud storage in open formats, such as Parquet or ORC, to store raw and processed data.

Some common use cases for using a lakehouse architecture are:

- Unified analytics: Ideal for organizations needing a single platform for both historical and real-time data analysis.

- Machine learning: Supports advanced analytics and machine learning workloads with integrated data management.

- Data governance: Ensures compliance and data quality across large datasets.

Internet of Things (IoT)

From a practical viewpoint, Internet of Things (IoT) represents any device that is connected to the Internet. This includes your PC, mobile phone, smart watch, smart thermostat, smart refrigerator, connected automobile, heart monitoring implants, and anything else that connects to the Internet and sends or receives data. The number of connected devices grows every day, as does the amount of data collected from them. Often this data is being collected in highly constrained, sometimes high-latency environments. In other cases, data is sent from low-latency environments by thousands or millions of devices, requiring the ability to rapidly ingest the data and process accordingly. Therefore, proper planning is required to handle these constraints and unique requirements.

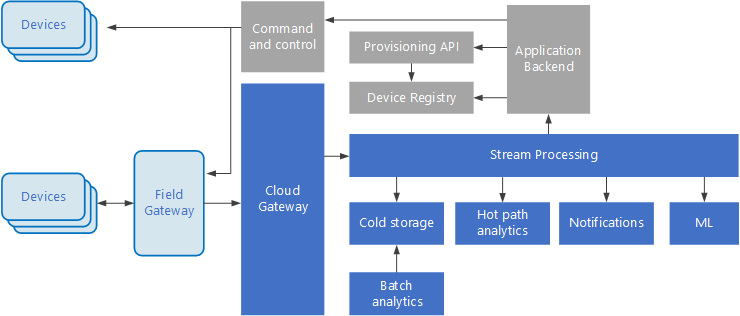

Event-driven architectures are central to IoT solutions. The following diagram shows a possible logical architecture for IoT. The diagram emphasizes the event-streaming components of the architecture.

The cloud gateway ingests device events at the cloud boundary, using a reliable, low latency messaging system.

Devices might send events directly to the cloud gateway, or through a field gateway. A field gateway is a specialized device or software, usually collocated with the devices, that receives events and forwards them to the cloud gateway. The field gateway might also preprocess the raw device events, performing functions such as filtering, aggregation, or protocol transformation.

After ingestion, events go through one or more stream processors that can route the data (for example, to storage) or perform analytics and other processing.

The following are some common types of processing. (This list is certainly not exhaustive.)

Writing event data to cold storage, for archiving or batch analytics.

Hot path analytics, analyzing the event stream in (near) real time, to detect anomalies, recognize patterns over rolling time windows, or trigger alerts when a specific condition occurs in the stream.

Handling special types of nontelemetry messages from devices, such as notifications and alarms.

Machine learning.

The boxes that are shaded gray show components of an IoT system that are not directly related to event streaming, but are included here for completeness.

The device registry is a database of the provisioned devices, including the device IDs and usually device metadata, such as location.

The provisioning API is a common external interface for provisioning and registering new devices.

Some IoT solutions allow command and control messages to be sent to devices.

Next steps

See the following relevant Azure services:

- Azure IoT Hub

- Azure Event Hubs

- Azure Stream Analytics

- Azure Data Explorer

- Microsoft Fabric

- Azure Databricks