Run Java with Jetty in Windows Azure

[Update 2011.01.17]NIO is no longer an issue in Windows Azure with SDK 1.3 (see post for more details)

[Update 2010.03.28] Included Jetty configuration information (see “Configure Jetty” section below)

Jetty is a Java-based, open source Web Server which provides a HTTP server and Servlet container capable of serving static and dynamic content either from a standalone or embedded instantiations. Jetty is used by many popular projects such as the Apache Geronimo JavaEE compliant application server, Apache ActiveMQ, Apache Cocoon, Apache Hadoop, Apache Maven, BEA WebLogic Event Server, Eucalyptus, FioranoMQ Java Messaging Server, Google App Engine and Web Toolkit plug-in for Eclipse, Google Android, RedHat JBoss, Sonic MQ, Spring Framework, Sybase EAServer, Zimbra Desktop, etc. (just to name a few).

The Jetty project provides:

- Asynchronous HTTP Server

- Standard based Servlet Container

- Web Sockets server

- Asynchronous HTTP Client

- OSGi, JNDI, JMX, JASPI, AJP support

From a application container perspective, Jetty can be used as an alternative deployment approach for the most popular frameworks in Java, such as Spring (and many of its sub-projects), EJB containers, integration with JEE servers as mentioned above, and a lot more, most supported via configuration as opposed to code-level integrations.

Java Support in Windows Azure

Since PDC09 (Professional Developers Conference), we’ve announced support for running Java and Tomcat in Windows Azure, and highlighted a project at Domino’s Pizza that ran a version of their online pizza ordering website in Windows Azure. Below is a short list of current resources that provide information on Java support in Windows Azure:

- https://code.msdn.microsoft.com/winazuretomcat

- https://www.interoperabilitybridges.com/projects/windows-azure-sdk-for-java.aspx

- https://microsoftpdc.com/Sessions/SVC50

- https://blogs.msdn.com/jonbox/archive/2009/11/17/domino-s-demonstrates-tomcat-site-on-windows-azure.aspx

However, this doesn’t mean that Tomcat is the only Java application container supported in Windows Azure. In fact, the approach basically consists of rolling in your own JRE (Java runtime), and any Java package that can be instantiated via the command line (instead of needing to install into the O/S). This Java application can then be packaged into a Worker Role application, then deployed into Windows Azure.

So why a Worker Role when we have a Web Role in Windows Azure? A Web Role essentially uses an IIS front-end, thus it supports ASP.NET applications, and any FastCGI extensions (Java is supported there too, but I’ll save that for another post). But a Worker Role gives us a bit more flexibility, as a Web Role may define a single HTTP endpoint and a single HTTPS endpoint for external clients, whereas a Worker Role may define any number of external endpoints using HTTP, HTTPS, or TCP. Each external endpoint defined for a role must listen on a unique port.

Thus for things like Tomcat (and Jetty) which want to do their own listening on ports as defined, is more suitable for Worker Roles in Windows Azure. And to do that, a bit of plumbing is required. The biggest challenge is actually hooking up the physical port that the Windows Azure fabric controller assigns to an instance of the Worker Role, even though logically the pool of Worker Roles are intended to receive external HTTP traffic on port 80 (or any port of your choosing). This is because internally inside of the Windows Azure environment, multiple VMs can reside on a single physical box, and that the load balancer may need to forward requests to dynamically provisioned instances residing in different locations, thus the fabric controller uses a different set of internal ports for this internal portion of the communication. Again for Web Roles we don’t need to be concerned with this as the fabric controller automatically configures IIS to listen on the correct internal port.

And this plumbing is exactly what the Tomcat Solution Accelerator provides (essentially making a call to the Worker Role environment and finding the right port, then making that change in server.xml for Catalina in Tomcat to pick up, then start the server to listen on that port), but if we want to do something else, like Jetty, then we need to do this plumbing ourselves. But don’t worry, it’s actually pretty simple, and really opens up the opportunity to deploy all kinds of stuff into Windows Azure.

Run Jetty in Windows Azure in <10 Minutes

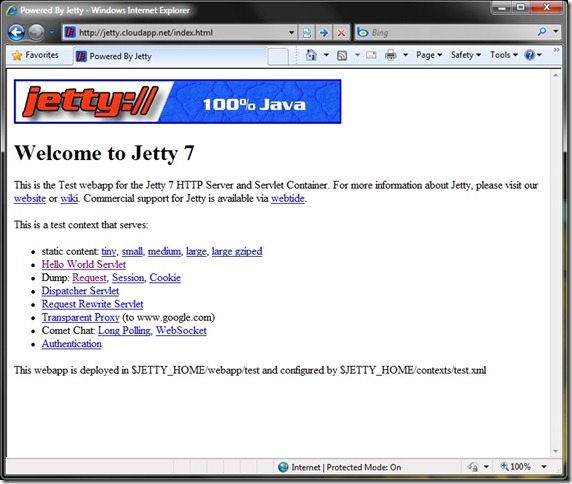

Below is a screenshot of my little Worker Role in Windows Azure running a Jetty Web server on port 80 (don’t try the URL; I didn’t leave the application running).

Worker Role Implementation

To do this, basically just start with a new Cloud project in Visual Studio, and add one Worker Role (just the same as a “Hello World” Worker Role app). And below is the only code I added inside of the Run() method in the WorkerRole class (minus the tracing code which I removed from this view):

string response = "";

try

{

System.IO.StreamReader sr;

string port = RoleEnvironment.CurrentRoleInstance.InstanceEndpoints["HttpIn"].IPEndpoint.Port.ToString();

string roleRoot = Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("RoleRoot");

string jettyHome = roleRoot + @"\approot\app\jetty7";

string jreHome = roleRoot + @"\approot\app\jre6";

Process proc = new Process();

proc.StartInfo.UseShellExecute = false;

proc.StartInfo.RedirectStandardOutput = true;

proc.StartInfo.FileName = String.Format("\"{0}\\bin\\java.exe\"", jreHome);

proc.StartInfo.Arguments = String.Format("-Djetty.port={0} -Djetty.home=\"{1}\" -jar \"{1}\\start.jar\"", port, jettyHome);

proc.EnableRaisingEvents = false;

proc.Start();

sr = proc.StandardOutput;

response = sr.ReadToEnd();

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

response = ex.Message;

Trace.TraceError(response);

}

Essentially, all this does is simply starting a new sub-process in the Worker Role instance to host and run the JRE and Jetty. The rest is figuring out how to provide the correct arguments to the process so that Jetty will load properly and it will listen to the port that this particular Worker Role instance is assigned to, as the forwarding port from the load balancer.

And of course, this is a pretty simplified scenario (and also because Jetty is pretty easy to launch), though more complicated configuration can also be supported, such as setting environment variables, changing XML configuration files (like what we have to do with Tomcat’s server.xml), executing a .bat file or other scripts, starting up multiple processes, etc.

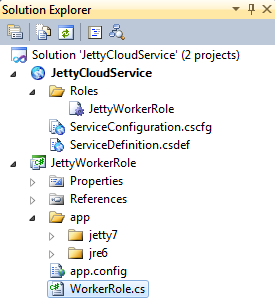

Add the Java and Jetty Assets

Next, copy and paste in the JRE and Jetty files into the WorkerRole’s folder. For me I put them under another folder called “app”, and in their individual folders “jre6” and “jetty7”. Under solution explorer in Visual Studio, this looks like:

Configure the External Input Endpoint

And the last significant change is to ServiceDefinition.csdef, by adding the below to the “WorkerRole” element:

<Endpoints>

<InputEndpoint name="HttpIn" port="80" protocol="tcp" />

</Endpoints>

Which is required to tell the fabric controller that the external input end point for this application is port 80.

Configure Jetty (updated 2010.03.28)

[Update 2011.01.17]NIO is no longer an issue in Windows Azure with SDK 1.3 (see post for more details). No need to replace NIO with BIO connector as described below.

There are many ways Jetty can be configured to run in Azure (such as for embedded server, starting from scratch instead of the entire distribution with demo apps), thus earlier I didn’t include how my deployment was configured, as each application can use different configurations, and I didn’t think my approach was necessarily the most ideal solution. Anyway, here is how I configured Jetty to run for the Worker Role code shown in this post.

First, I had to change the default NIO ChannelConnector that Jetty was using, from the new/non-blocking I/O connector to the traditional blocking IO and threading model BIO SocketConnector (because the loopback connection required by NIO doesn’t seem to work in Windows Azure).

This can be done in etc/jetty.xml, where we set connectors, by editing the New element to use org.eclipse.jetty.server.bio.SocketConnector instead of the default org.eclipse.jetty.server.nio.SelectChannelConnector, and remove the few additional options for the NIO connector. The resulting block looks like this:

<Call name="addConnector">

<Arg>

<New class="org.eclipse.jetty.server.bio.SocketConnector">

<Set name="host"><SystemProperty name="jetty.host" /></Set>

<Set name="port"><SystemProperty name="jetty.port" default="8080" /></Set>

<Set name="maxIdleTime">300000</Set>

</New>

</Arg>

</Call>

Now, I chose the approach to use JRE and Jetty files simply as application assets (read-only), mostly because this is a simpler exercise, and that I wanted to streamline the Worker Role implementation as much as possible, without having to do more configurations on the .NET side than necessary (such as due to dependencies on allocating a separate local resource/storage for Jetty, copy files over from the deployment, and use that as a runtime environment where it can write to files).

As a result of this approach, I needed to make sure that Jetty doesn’t need to write to any files locally when the server is started. Description of what I did:

- etc/jetty.xml – commented out the default “RequestLog” handler so that Jetty doesn’t need to write to that log

- etc/jetty.xml – changed addBean “org.eclipse.jetty.deploy.WebAppDeployer”’s “extract” property to “false” so that it doesn’t extract the .war files

- contexts/test.xml – changed <Set name="extractWAR">’s property to “false” so that it doesn’t extract the .war files as well

This step above is considered optional, as you can also create a local storage and copy the jetty and jre directories over, then launch the JRE and Jetty using those files. But you’ll also need more code in the Worker Role to support that, as well as using a different location to find the JRE and Jetty to launch the sub-process (the Tomcat Solution Accelerator used that approach).

|

Download the project The entire solution (2.3MB) including the Jetty assets as configured (but minus the ~80MB of JRE binaries), can be downloaded from Skydrive. |

Summary

The approach I described in this post uses JRE and Jetty files simply as application assets, since from a development process perspective I was thinking that development and testing of the Java applications to be deployed in Jetty should be done outside of the Windows Azure environment, and Windows Azure can be viewed as the staging/production environment for the applications. From that perspective, we shouldn’t need to have hot deployment of applications into Jetty, and other things like log files written and data/content used by Jetty and the applications, should be persisted to and retrieved from Windows Azure Storage and/or SQL Azure services.

The implementation is really just intended for deployment into the Windows Azure cloud environment (or the local dev fabric for testing purposes). For developing applications to run in Jetty, we can use any tools we prefer in the Java ecosystem – Eclipse, NetBeans, IntelliJ, Emacs, etc., and do all of the unit testing and packaging into supported forms (such as .war packages). That way, development efforts on the Java side can be just as productive, while the only work that we really need to do is a one-time integration and configuration of the staging/production runtime, if we choose to use Windows Azure as the cloud platform to host an application.

Similarly, for developing and unit testing the C# managed code inside the Worker Role, we also don’t have to always work inside the Windows Azure environment. In fact, it may be quicker to have the same code written as a Console application and test it there first, then port over to the Worker Role as by that time we’d only need to be concerned with integrating with specific items inside of the Windows Azure environment. And of course, we can re-factor the code to be more parameter-driven so the Java integration code can be nicely decoupled from the Windows Azure integration code.

Anyway, simple exercise done. Now we can try some more complicated things such as Geronimo, GlassFish, Hadoop, etc. Stay tuned for upcoming posts about these efforts.

Lastly, these are the tools I used:

- Visual Studio 2010 RC (Version 10.0.30128.1 RC1Rel; 2/10/2010)

- Windows Azure Tools for Visual Studio (Version 1.1.30131.1501; 2/1/2010)

- Windows Azure SDK (2/1/2010)

- Java SE 6 Update 18 (build 1.6.0_18-b07)

- Jetty 7 (7.0.1.v20091125)

Comments

Anonymous

September 29, 2010

JavaOne has always been one of my favorite technology conferences, and this year I had the privilegeAnonymous

September 29, 2010

JavaOne has always been one of my favorite technology conferences, and this year I had the privilegeAnonymous

September 29, 2010

JavaOne has always been one of my favorite technology conferences, and this year I had the privilegeAnonymous

October 04, 2010

The comment has been removedAnonymous

December 29, 2010

Hi, Any possibility of getting and releasing an Implementation of Solr on Azure ? Lucene.net is available but it would seem that Solr would be entirely more scalable and if Java is supported then it would be MUCH better to use Solr ? Would be great to get a blog post on Solr / setting it up / scaling it on Azure ? ThanksAnonymous

January 05, 2011

You have an existing Java application or are developing a new one and want to take advantage of the cloudAnonymous

January 05, 2011

You have an existing Java application or are developing a new one and want to take advantage of the cloudAnonymous

January 17, 2011

At PDC10 (Microsoft’s Professional Developers Conference 2010), Microsoft has again provided affirmationAnonymous

March 03, 2011

This post is built upon the work of Mario Kosmiskas and David C. Chou’s prior postings – from here: httpAnonymous

March 03, 2011

This post is built upon the work of Mario Kosmiskas and David C. Chou’s prior postings – from here: httpAnonymous

March 16, 2012

Windows Azure is a Platform as a Service – a PaaS – that runs code you write. That code doesn’t