Discriminated Unions

Discriminated unions provide support for values that can be one of a number of named cases, possibly each with different values and types. Discriminated unions are useful for heterogeneous data; data that can have special cases, including valid and error cases; data that varies in type from one instance to another; and as an alternative for small object hierarchies. In addition, recursive discriminated unions are used to represent tree data structures.

Syntax

[ attributes ]

type [accessibility-modifier] type-name =

| case-identifier1 [of [ fieldname1 : ] type1 [ * [ fieldname2 : ] type2 ...]

| case-identifier2 [of [fieldname3 : ]type3 [ * [ fieldname4 : ]type4 ...]

[ member-list ]

Remarks

Discriminated unions are similar to union types in other languages, but there are differences. As with a union type in C++ or a variant type in Visual Basic, the data stored in the value is not fixed; it can be one of several distinct options. Unlike unions in these other languages, however, each of the possible options is given a case identifier. The case identifiers are names for the various possible types of values that objects of this type could be; the values are optional. If values are not present, the case is equivalent to an enumeration case. If values are present, each value can either be a single value of a specified type, or a tuple that aggregates multiple fields of the same or different types. You can give an individual field a name, but the name is optional, even if other fields in the same case are named.

Accessibility for discriminated unions defaults to public.

For example, consider the following declaration of a Shape type.

type Shape =

| Rectangle of width : float * length : float

| Circle of radius : float

| Prism of width : float * float * height : float

The preceding code declares a discriminated union Shape, which can have values of any of three cases: Rectangle, Circle, and Prism. Each case has a different set of fields. The Rectangle case has two named fields, both of type float, that have the names width and length. The Circle case has just one named field, radius. The Prism case has three fields, two of which (width and height) are named fields. Unnamed fields are referred to as anonymous fields.

You construct objects by providing values for the named and anonymous fields according to the following examples.

let rect = Rectangle(length = 1.3, width = 10.0)

let circ = Circle (1.0)

let prism = Prism(5., 2.0, height = 3.0)

This code shows that you can either use the named fields in the initialization, or you can rely on the ordering of the fields in the declaration and just provide the values for each field in turn. The constructor call for rect in the previous code uses the named fields, but the constructor call for circ uses the ordering. You can mix the ordered fields and named fields, as in the construction of prism.

The option type is a simple discriminated union in the F# core library. The option type is declared as follows.

// The option type is a discriminated union.

type Option<'a> =

| Some of 'a

| None

The previous code specifies that the type Option is a discriminated union that has two cases, Some and None. The Some case has an associated value that consists of one anonymous field whose type is represented by the type parameter 'a. The None case has no associated value. Thus the option type specifies a generic type that either has a value of some type or no value. The type Option also has a lowercase type alias, option, that is more commonly used.

The case identifiers can be used as constructors for the discriminated union type. For example, the following code is used to create values of the option type.

let myOption1 = Some(10.0)

let myOption2 = Some("string")

let myOption3 = None

The case identifiers are also used in pattern matching expressions. In a pattern matching expression, identifiers are provided for the values associated with the individual cases. For example, in the following code, x is the identifier given the value that is associated with the Some case of the option type.

let printValue opt =

match opt with

| Some x -> printfn "%A" x

| None -> printfn "No value."

In pattern matching expressions, you can use named fields to specify discriminated union matches. For the Shape type that was declared previously, you can use the named fields as the following code shows to extract the values of the fields.

let getShapeWidth shape =

match shape with

| Rectangle(width = w) -> w

| Circle(radius = r) -> 2. * r

| Prism(width = w) -> w

Normally, the case identifiers can be used without qualifying them with the name of the union. If you want the name to always be qualified with the name of the union, you can apply the RequireQualifiedAccess attribute to the union type definition.

Unwrapping Discriminated Unions

In F# Discriminated Unions are often used in domain-modeling for wrapping a single type. It's easy to extract the underlying value via pattern matching as well. You don't need to use a match expression for a single case:

let ([UnionCaseIdentifier] [values]) = [UnionValue]

The following example demonstrates this:

type ShaderProgram = | ShaderProgram of id:int

let someFunctionUsingShaderProgram shaderProgram =

let (ShaderProgram id) = shaderProgram

// Use the unwrapped value

...

Pattern matching is also allowed directly in function parameters, so you can unwrap a single case there:

let someFunctionUsingShaderProgram (ShaderProgram id) =

// Use the unwrapped value

...

Struct Discriminated Unions

You can also represent Discriminated Unions as structs. This is done with the [<Struct>] attribute.

[<Struct>]

type SingleCase = Case of string

[<Struct>]

type Multicase =

| Case1 of string

| Case2 of int

| Case3 of double

Because these are value types and not reference types, there are extra considerations compared with reference discriminated unions:

- They are copied as value types and have value type semantics.

- You cannot use a recursive type definition with a multicase struct discriminated union.

Before F# 9, there was a requirement for each case to specify a unique case name (within the union). Starting with F# 9, the limitation is lifted.

Using Discriminated Unions Instead of Object Hierarchies

You can often use a discriminated union as a simpler alternative to a small object hierarchy. For example, the following discriminated union could be used instead of a Shape base class that has derived types for circle, square, and so on.

type Shape =

// The value here is the radius.

| Circle of float

// The value here is the side length.

| EquilateralTriangle of double

// The value here is the side length.

| Square of double

// The values here are the height and width.

| Rectangle of double * double

Instead of a virtual method to compute an area or perimeter, as you would use in an object-oriented implementation, you can use pattern matching to branch to appropriate formulas to compute these quantities. In the following example, different formulas are used to compute the area, depending on the shape.

let pi = 3.141592654

let area myShape =

match myShape with

| Circle radius -> pi * radius * radius

| EquilateralTriangle s -> (sqrt 3.0) / 4.0 * s * s

| Square s -> s * s

| Rectangle(h, w) -> h * w

let radius = 15.0

let myCircle = Circle(radius)

printfn "Area of circle that has radius %f: %f" radius (area myCircle)

let squareSide = 10.0

let mySquare = Square(squareSide)

printfn "Area of square that has side %f: %f" squareSide (area mySquare)

let height, width = 5.0, 10.0

let myRectangle = Rectangle(height, width)

printfn "Area of rectangle that has height %f and width %f is %f" height width (area myRectangle)

The output is as follows:

Area of circle that has radius 15.000000: 706.858347

Area of square that has side 10.000000: 100.000000

Area of rectangle that has height 5.000000 and width 10.000000 is 50.000000

Using Discriminated Unions for Tree Data Structures

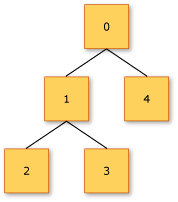

Discriminated unions can be recursive, meaning that the union itself can be included in the type of one or more cases. Recursive discriminated unions can be used to create tree structures, which are used to model expressions in programming languages. In the following code, a recursive discriminated union is used to create a binary tree data structure. The union consists of two cases, Node, which is a node with an integer value and left and right subtrees, and Tip, which terminates the tree.

type Tree =

| Tip

| Node of int * Tree * Tree

let rec sumTree tree =

match tree with

| Tip -> 0

| Node(value, left, right) -> value + sumTree (left) + sumTree (right)

let myTree =

Node(0, Node(1, Node(2, Tip, Tip), Node(3, Tip, Tip)), Node(4, Tip, Tip))

let resultSumTree = sumTree myTree

In the previous code, resultSumTree has the value 10. The following illustration shows the tree structure for myTree.

Discriminated unions work well if the nodes in the tree are heterogeneous. In the following code, the type Expression represents the abstract syntax tree of an expression in a simple programming language that supports addition and multiplication of numbers and variables. Some of the union cases are not recursive and represent either numbers (Number) or variables (Variable). Other cases are recursive, and represent operations (Add and Multiply), where the operands are also expressions. The Evaluate function uses a match expression to recursively process the syntax tree.

type Expression =

| Number of int

| Add of Expression * Expression

| Multiply of Expression * Expression

| Variable of string

let rec Evaluate (env: Map<string, int>) exp =

match exp with

| Number n -> n

| Add(x, y) -> Evaluate env x + Evaluate env y

| Multiply(x, y) -> Evaluate env x * Evaluate env y

| Variable id -> env[id]

let environment = Map [ "a", 1; "b", 2; "c", 3 ]

// Create an expression tree that represents

// the expression: a + 2 * b.

let expressionTree1 = Add(Variable "a", Multiply(Number 2, Variable "b"))

// Evaluate the expression a + 2 * b, given the

// table of values for the variables.

let result = Evaluate environment expressionTree1

When this code is executed, the value of result is 5.

Mutually Recursive Discriminated Unions

Discriminated unions in F# can be mutually recursive, meaning that multiple union types can reference each other in a recursive manner. This is useful when modeling hierarchical or interconnected structures. To define mutually recursive discriminated unions, use the and keyword.

For example, consider an abstract syntax tree (AST) representation where expressions can include statements, and statements can contain expressions:

type Expression =

| Literal of int

| Variable of string

| Operation of string * Expression * Expression

and Statement =

| Assign of string * Expression

| Sequence of Statement list

| IfElse of Expression * Statement * Statement

Members

It is possible to define members on discriminated unions. The following example shows how to define a property and implement an interface:

open System

type IPrintable =

abstract Print: unit -> unit

type Shape =

| Circle of float

| EquilateralTriangle of float

| Square of float

| Rectangle of float * float

member this.Area =

match this with

| Circle r -> Math.PI * (r ** 2.0)

| EquilateralTriangle s -> s * s * sqrt 3.0 / 4.0

| Square s -> s * s

| Rectangle(l, w) -> l * w

interface IPrintable with

member this.Print () =

match this with

| Circle r -> printfn $"Circle with radius %f{r}"

| EquilateralTriangle s -> printfn $"Equilateral Triangle of side %f{s}"

| Square s -> printfn $"Square with side %f{s}"

| Rectangle(l, w) -> printfn $"Rectangle with length %f{l} and width %f{w}"

.Is* properties on cases

Since F# 9, discriminated unions expose auto-generated .Is* properties for each case, allowing you to check if a value is of a particular case.

This is how it can be used:

type Contact =

| Email of address: string

| Phone of countryCode: int * number: string

type Person = { name: string; contact: Contact }

let canSendEmailTo person =

person.contact.IsEmail // .IsEmail is auto-generated

Common attributes

The following attributes are commonly seen in discriminated unions:

[<RequireQualifiedAccess>][<NoEquality>][<NoComparison>][<Struct>]