Application design of mission-critical workloads on Azure

When you design an application, both functional and non-functional application requirements are critical. This design area describes architecture patterns and scaling strategies that can help make your application resilient to failures.

Important

This article is part of the Azure Well-Architected Framework mission-critical workload series. If you aren't familiar with this series, we recommend that you start with What is a mission-critical workload?.

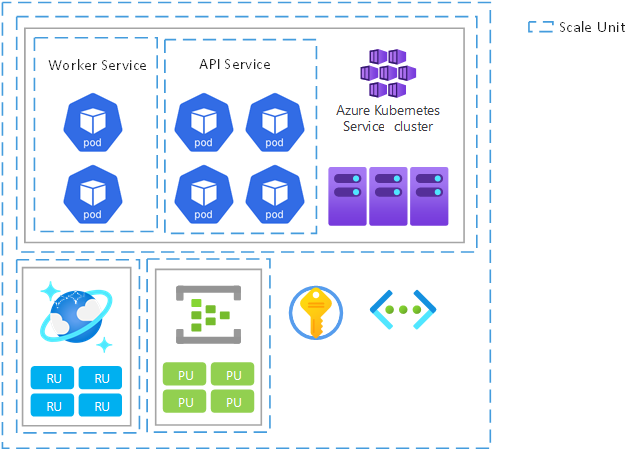

Scale-unit architecture

All functional aspects of a solution must be capable of scaling to meet changes in demand, ideally autoscaling in response to load. We recommend that you use a scale-unit architecture to optimize end-to-end scalability through compartmentalization, and also to standardize the process of adding and removing capacity. A scale unit is a logical unit or function that can be scaled independently. A unit can be made up of code components, application hosting platforms, the deployment stamps that cover the related components, and even subscriptions to support multi-tenant requirements.

We recommend this approach because it addresses the scale limits of individual resources and the entire application. It helps with complex deployment and update scenarios because a scale unit can be deployed as one unit. Also, you can test and validate specific versions of components in a unit before directing user traffic to it.

Suppose your mission-critical application is an online product catalog. It has a user flow for processing product comments and ratings. The flow uses APIs to retrieve and post comments and ratings, and supporting components like an OAuth endpoint, datastore, and message queues. The stateless API endpoints represent granular functional units that must adapt to changes on demand. The underlying application platform must also be able to scale accordingly. To avoid performance bottlenecks, the downstream components and dependencies must also scale to an appropriate degree. They can either scale independently, as separate scale units, or together, as part of a single logical unit.

Example scale units

The following image shows the possible scopes for scale units. The scopes range from microservice pods to cluster nodes and regional deployment stamps.

Design considerations

Scope. The scope of a scale unit, the relationship between scale units, and their components should be defined according to a capacity model. Take into consideration non-functional requirements for performance.

Scale limits. Azure subscription scale limits and quotas might have a bearing on application design, technology choices, and the definition of scale units. Scale units can help you bypass the scale limits of a service. For example, if an AKS cluster in one unit can have only 1,000 nodes, you can use two units to increase that limit to 2,000 nodes.

Expected load. Use the number of requests for each user flow, the expected peak request rate (requests per second), and daily/weekly/seasonal traffic patterns to inform core scale requirements. Also factor in the expected growth patterns for both traffic and data volume.

Acceptable degraded performance. Determine whether a degraded service with high response times is acceptable under load. When you're modeling required capacity, the required performance of the solution under load is a critical factor.

Non-functional requirements. Technical and business scenarios have distinct considerations for resilience, availability, latency, capacity, and observability. Analyze these requirements in the context of key end-to-end user flows. You'll have relative flexibility in the design, decision making, and technology choices at a user-flow level.

Design recommendations

Define the scope of a scale unit and the limits that will trigger the unit to scale.

Ensure that all application components can scale independently or as part of a scale unit that includes other related components.

Define the relationship between scale units, based on a capacity model and non-functional requirements.

Define a regional deployment stamp to unify the provisioning, management, and operation of regional application resources into a heterogenous but interdependent scale unit. As load increases, extra stamps can be deployed, within the same Azure region or different ones, to horizontally scale the solution.

Use an Azure subscription as the scale unit so that scale limits within a single subscription don't constrain scalability. This approach applies to high-scale application scenarios that have significant traffic volume.

Model required capacity around identified traffic patterns to make sure sufficient capacity is provisioned at peak times to prevent service degradation. Alternatively, optimize capacity during off-peak hours.

Measure the time required to do scale-out and scale-in operations to ensure that the natural variations in traffic don't create an unacceptable level of service degradation. Track the scale operation durations as an operational metric.

Note

When you deploy in an Azure landing zone, ensure that the landing zone subscription is dedicated to the application to provide a clear management boundary and to avoid the Noisy Neighbor antipattern.

Global distribution

It's impossible to avoid failure in any highly distributed environment. This section provides strategies to mitigate many fault scenarios. The application must be able to withstand regional and zonal failures. It must be deployed in an active/active model so that the load is distributed among all regions.

Watch this video to get an overview of how to plan for failures in mission-critical applications and maximize resiliency:

Design considerations

Redundancy. Your application must be deployed to multiple regions. Additionally, within a region, we strongly recommend that you use availability zones to allow for fault tolerance at the datacenter level. Availability zones have a latency perimeter of less than 2 milliseconds between availability zones. For workloads that are "chatty" across zones, this latency can introduce a performance penalty for interzone data transfer.

Active/active model. An active/active deployment strategy is recommended because it maximizes availability and provides a higher composite service-level agreement (SLA). However, it can introduce challenges around data synchronization and consistency for many application scenarios. Address the challenges at a data platform level while considering the trade-offs of increased cost and engineering effort.

An active/active deployment across multiple cloud providers is a way to potentially mitigate dependency on global resources within a single cloud provider. However, a multicloud active/active deployment strategy introduces a significant amount of complexity around CI/CD. Also, given the differences in resource specifications and capabilities among cloud providers, you'd need specialized deployment stamps for each cloud.

Geographical distribution. The workload might have compliance requirements for geographical data residency, data protection, and data retention. Consider whether there are specific regions where data must reside or where resources need to be deployed.

Request origin. The geographic proximity and density of users or dependent systems should inform design decisions about global distribution.

Connectivity. How the workload is accessed by users or external systems will influence your design. Consider whether the application is available over the public internet or private networks that use either VPN or Azure ExpressRoute circuits.

For design recommendations and configuration choices at the platform level, see Application platform: Global distribution.

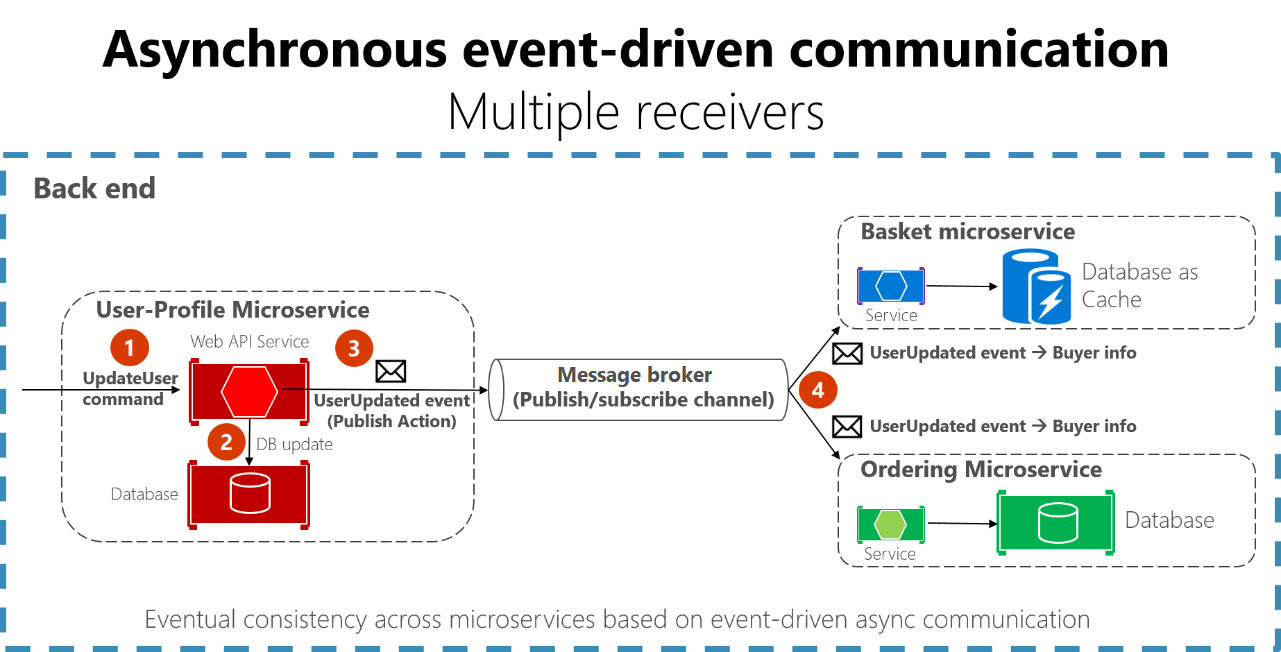

Loosely coupled event-driven architecture

Coupling enables interservice communication via well-defined interfaces. A loose coupling allows an application component to operate independently. A microservices architecture style is consistent with mission-critical requirements. It facilitates high availability by preventing cascading failures.

For loose coupling, we strongly recommend that you incorporate event-driven design. Asynchronous message processing through an intermediary can build resiliency.

In some scenarios, applications can combine loose and tight coupling, depending on business objectives.

Design considerations

Runtime dependencies. Loosely coupled services shouldn't be constrained to use the same compute platform, programming language, runtime, or operating system.

Scaling. Services should be able to scale independently. Optimize the use of infrastructure and platform resources.

Fault tolerance. Failures should be handled separately and shouldn’t affect client transactions.

Transactional integrity. Consider the effect of data creation and persistence that happens in separate services.

Distributed tracing. End-to-end tracing might require complex orchestration.

Design recommendations

Align microservice boundaries with critical user flows.

Use event-driven asynchronous communication where possible to support sustainable scale and optimal performance.

Use patterns like Outbox and Transactional Session to guarantee consistency so that every message is processed correctly.

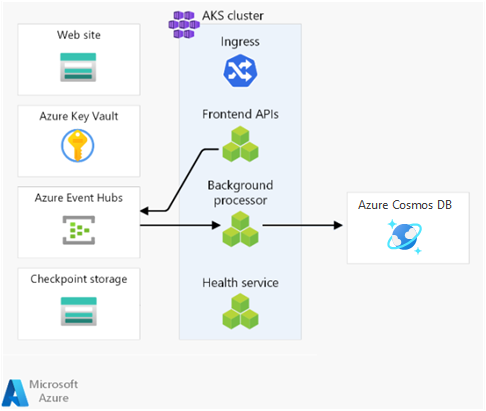

Example: Event-driven approach

The Mission-Critical Online reference implementation uses microservices to process a single business transaction. It applies write operations asynchronously with a message broker and worker. Read operations are synchronous, with the result directly returned to the caller.

Resiliency patterns and error handling in application code

A mission-critical application must be designed to be resilient so that it addresses as many failure scenarios as possible. This resiliency maximizes service availability and reliability. The application should have self-healing capabilities, which you can implement by using design patterns like Retries with Backoff and Circuit Breaker.

For non-transient failures that you can't fully mitigate in application logic, the health model and operational wrappers need to take corrective action. Application code must incorporate proper instrumentation and logging to inform the health model and facilitate subsequent troubleshooting or root cause analysis as required. You need to implement distributed tracing to provide the caller with a comprehensive error message that includes a correlation ID when a failure occurs.

Tools like Application Insights can help you query, correlate, and visualize application traces.

Design considerations

Proper configurations. It's not uncommon for transient problems to cause cascading failures. For example, retry without appropriate back-off exacerbates the problem when a service is being throttled. You can space retry delays linearly or increase them exponentially to back off through growing delays.

Health endpoints. You can expose functional checks within application code by using health endpoints that external solutions can poll to retrieve application component health status.

Design recommendations

Here are some common software engineering patterns for resilient applications:

| Pattern | Summary |

|---|---|

| Queue-Based Load Leveling | Introduces a buffer between consumers and requested resources to ensure consistent load levels. As consumer requests are queued, a worker process handles them against the requested resource at a pace that's set by the worker and by the requested resource's ability to process the requests. If consumers expect replies to their requests, you need to implement a separate response mechanism. Apply a prioritized order so that the most important activities are performed first. |

| Circuit Breaker | Provides stability by either waiting for recovery or quickly rejecting requests rather than blocking while waiting for an unavailable remote service or resource. This pattern also handles faults that might take a variable amount of time to recover from when a connection is made to a remote service or resource. |

| Bulkhead | Attempts to partition service instances into groups based on load and availability requirements, isolating failures to sustain service functionality. |

| Saga | Manages data consistency across microservices that have independent datastores by ensuring that services update each other through defined event or message channels. Each service performs local transactions to update its own state and publishes an event to trigger the next local transaction in the saga. If a service update fails, the saga runs compensating transactions to counteract preceding service update steps. Individual service update steps can themselves implement resiliency patterns, such as retry. |

| Health Endpoint Monitoring | Implements functional checks in an application that external tools can access through exposed endpoints at regular intervals. You can interpret responses from the endpoints by using key operational metrics to inform application health and trigger operational responses, like raising an alert or performing a compensating rollback deployment. |

| Retry | Handles transient failures elegantly and transparently. - Cancel if the fault is unlikely to be transient and is unlikely to succeed if the operation is attempted again. - Retry if the fault is unusual or rare and the operation is likely to succeed if attempted again immediately. - Retry after a delay if the fault is caused by a condition that might need a short time to recover, like network connectivity or high-load failures. Apply a suitable back-off strategy as retry delays increase. |

| Throttling | Controls the consumption of resources used by application components, protecting them from becoming over-encumbered. When a resource reaches a load threshold, it defers lower-priority operations and degrading non-essential functionality so that essential functionality can continue until sufficient resources are available to return to normal operation. |

Here are some additional recommendations:

Use vendor-provided SDKs, like the Azure SDKs, to connect to dependent services. Use built-in resiliency capabilities instead of implementing custom functionality.

Apply a suitable back-off strategy when retrying failed dependency calls to avoid a self-inflicted DDoS scenario.

Define common engineering criteria for all application microservice teams to drive consistency and speed in the use of application-level resiliency patterns.

Implement resiliency patterns by using proven standardized packages, like Polly for C# or Sentinel for Java.

Use correlation IDs for all trace events and log messages to link them to a given request. Return correlation IDs to the caller for all calls, not just failed requests.

Use structured logging for all log messages. Select a unified operational data sink for application traces, metrics, and logs to enable operators to easily debug problems. For more information, see Collect, aggregate, and store monitoring data for cloud applications.

Ensure that operational data is used together with business requirements to inform an application health model.

Programming language selection

It's important to select the right programming languages and frameworks. These decisions are often driven by the skill sets or standardized technologies in the organization. However, it's essential to evaluate the performance, resilience, and overall capabilities of various languages and frameworks.

Design considerations

Development kit capabilities. There are differences in the capabilities that are offered by Azure service SDKs in various languages. These differences might influence your choice of an Azure service or programming language. For example, if Azure Cosmos DB is a feasible option, Go might not be an appropriate development language because there's no first-party SDK.

Feature updates. Consider how often the SDK is updated with new features for the selected language. Commonly used SDKs, like .NET and Java libraries, are updated frequently. Other SDKs or SDKs for other languages might be updated less frequently.

Multiple programming languages or frameworks. You can use multiple technologies to support various composite workloads. However, you should avoid sprawl because it introduces management complexity and operational challenges.

Compute option. Legacy or proprietary software might not run in PaaS services. Also, you might not be able to include legacy or proprietary software in containers.

Design recommendations

Evaluate all relevant Azure SDKs for the capabilities you need and your chosen programming languages. Verify alignment with non-functional requirements.

Optimize the selection of programming languages and frameworks at the microservice level. Use multiple technologies as appropriate.

Prioritize the .NET SDK to optimize reliability and performance. .NET Azure SDKs typically provide more capabilities and are updated frequently.

Next step

Review the considerations for the application platform.