Architectural approaches for messaging in multitenant solutions

Asynchronous messaging and event-driven communication are critical assets when building a distributed application that's composed of several internal and external services. When you design a multitenant solution, it's crucial to conduct a preliminary analysis to define how to share or partition messages that pertain to different tenants.

Sharing the same messaging system or event-streaming service can significantly reduce the operational cost and management complexity. However, using a dedicated messaging system for each tenant provides better data isolation, reduces the risk of data leakage, eliminates the Noisy Neighbor issue, and allows to charge your Azure costs back to your tenants easily.

In this article, you can find a distinction between messages and events, and you'll find guidelines that solution architects can follow when deciding which approach to use for a messaging or eventing infrastructure in a multitenant solution.

Messages, data points, and discrete events

All messaging systems have similar functionalities, transport protocols, and usage scenarios. For example, most of the modern messaging systems support asynchronous communications that use volatile or persistent queues, AMQP and HTTPS transport protocols, at-least-once delivery, and so on. However, by looking more closely at the type of published information and how data is consumed and processed by client applications, we can distinguish between different kinds of messages and events. There's an essential distinction between services that deliver an event and systems that send a message. For more information, see the following resources:

- Choose between Azure messaging services - Event Grid, Event Hubs, and Service Bus

- Events, Data Points, and Messages - Choosing the right Azure messaging service for your data

Events

An event is a lightweight notification of a condition or a state change. Events can be discrete units or part of a series. Events are messages that don't generally convey a publisher's intent other than to inform. An event captures a fact and communicates it to other services or components. A consumer of the event can process the event as it pleases and doesn't fulfill any specific expectations the publisher holds. We can classify events into two main categories:

- Discrete events hold information about specific actions that the publishing application has carried out. When using asynchronous event-driven communication, an application publishes a notification event when something happens within its domain. One or more consuming applications needs to be aware of this state change, like a price change in a product catalog application. Consumers subscribe to the events to receive them asynchronously. When a given event happens, the consuming applications might update their domain entities, which can cause more integration events to be published.

- Series events carry informational data points, such as temperature readings from devices for analysis or user actions in a click-analytics solution, as elements in an ongoing, continuous stream. An event stream is related to a specific context, like the temperature or humidity reported by a field device. All the events related to the same context have a strict temporal order that matters when processing these events with an event stream processing engine. Analyzing streams of events that carry data points requires accumulating these events in a buffer that spans a desired time window. Or it can be in a selected number of items and then processing these events, by using a near-real-time solution or machine-trained algorithm. The analysis of a series of events can yield signals, like the average of a value measured over a time window that crosses a threshold. Those signals can then be raised as discrete, actionable events.

Discrete events report state changes and are actionable. The event payload has information about what happened, but, in general, it doesn't have the complete data that triggered the event. For example, an event notifies consumers that a reporting application created a new file in a storage account. The event payload might have general information about the file, but it doesn't have the file itself. Discrete events are ideal for serverless solutions that need to scale.

Series events report a condition and are analyzable. Discrete events are time-ordered and interrelated. In some contexts, the consumer needs to receive the complete sequence of events to analyze what happened and to take the necessary action.

Messages

Messages contain raw data that's produced by a service to be consumed or stored elsewhere. Messages often carry information necessary for a receiving service to execute steps in a workflow or a processing chain. An example of this kind of communication is the Command pattern. The publisher may also expect the receiver(s) of a message to execute a series of actions and to report back the outcome of their processing with an asynchronous message. A contract exists between the message publisher and message receiver(s). For example, the publisher sends a message with some raw data and expects the consumer to create a file from that data and send back a response message when done. In other situations, a sender process could send an asynchronous, one-way message to ask another service to perform a given operation, but with no expectation of getting back an acknowledgment or response message from it.

This kind of contractual message handling is quite different from a publisher who's publishing discrete events to an audience of consumer agents, without any specific expectation of how they will handle these notifications.

Example scenarios

Here is a list of some example multitenant scenarios for messages, data points, and discrete events:

- Discrete events:

- A music-sharing platform tracks the fact that a specific user in a specific tenant has listened to a particular music track.

- In an online store web application, the catalog application sends an event using the Publisher-Subscriber pattern to other applications to notify them that an item price has changed.

- A manufacturing company pushes real-time information to customers and third parties about equipment maintenance, systems health, and contract updates.

- Data points:

- A building control system receives telemetry events, such as temperature or humidity readings from sensors that belong to multiple customers.

- An event-driven monitoring system receives and processes diagnostics logs in a near-real-time fashion from multiple services, such as web servers.

- A client-side script on a web page collects user actions and sends them to a click-analytics solution.

- Messages:

- A B2B finance application receives a message to begin processing a tenant's banking records.

- A long-running workflow receives a message that triggers the execution of the next step.

- The basket application of an online store application sends a CreateOrder command, by using an asynchronous, persistent message to the ordering application.

Key considerations and requirements

The deployment and tenancy model that you choose for your solution has a deep impact on security, performance, data isolation, management, and the ability to cross-charge resource costs to tenants. This analysis includes the model that you select for your messaging and eventing infrastructure. In this section, we review some of the key decisions you must make when you plan for a messaging system in your multitenant solution.

Scale

The number of tenants, the complexity of message flows and event streams, the volume of messages, the expected traffic profile, and the isolation level should drive the decisions when planning for a messaging or eventing infrastructure.

The first step consists in conducting exhaustive capacity planning and establishing the necessary maximum capacity for a messaging system in terms of throughput to properly handle the expected volume of messages under regular or peak traffic.

Some service offerings, such as the Azure Service Bus Premium tier, provide resource isolation at the CPU and memory level so that each customer workload runs in isolation. This resource container is called a messaging unit. Each premium namespace is allocated at least one messaging unit. You can purchase 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16 messaging units for each Service Bus Premium namespace. A single workload or entity can span multiple messaging units, and you can change the number of messaging units as necessary. The result is a predictable and repeatable performance for your Service Bus-based solution. For more information, see Service Bus Premium and Standard messaging tiers. Likewise, Azure Event Hubs pricing tiers allow you to size the namespace, based on the expected volume of inbound and outbound events. For example, the Premium offering is billed by processing units (PUs), which correspond to a share of isolated resources (CPU, memory, and storage) in the underlying infrastructure. The effective ingest and stream throughput per PU will depend on the following factors:

- Number of producers and consumers

- Payload size

- Partition count

- Egress request rate

- Usage of Event Hubs Capture, Schema Registry, and other advanced features

For more information, see Overview of Event Hubs Premium.

When your solution handles a considerable number of tenants, and you decide to adopt a separate messaging system for each tenant, you need to have a consistent strategy to automate the deployment, monitoring, alerting, and scaling of each infrastructure, separately from one other.

For example, a messaging system for a given tenant could be deployed during the provisioning process using an infrastructure as code (IaC) tool such a Terraform, Bicep, or Azure Resource Manager (ARM) JSON templates and a DevOps system such as Azure DevOps or GitHub Actions. For more information, see Architectural approaches for the deployment and configuration of multitenant solutions.

The messaging system could be sized with a maximum throughput in messages per unit of time. If the system supports dynamic autoscaling, its capacity could be increased or decreased automatically, based on the traffic conditions and metrics to meet the expected service-level agreement.

Performance predictability and reliability

When designing and building a messaging system for a limited number of tenants, using a single messaging system could be an excellent solution to meet the functional requirements, in terms of throughput, and it could reduce the total cost of ownership. A multitenant application might share the same messaging entities, such as queues and topics across multiple customers. Or they might use a dedicated set of components for each, in order to increase tenant isolation. On the other hand, sharing the same messaging infrastructure across multiple tenants could expose the entire solution to the Noisy Neighbor issue. The activity of one tenant could harm other tenants, in terms of performance and operability.

In this case, the messaging system should be properly sized to sustain the expected traffic load at peak time. Ideally, it should support autoscaling. The messaging system should dynamically scale out when the traffic increases and scale in when the traffic decreases. A dedicated messaging system for each tenant could also mitigate the Noisy Neighbor risk, but managing a large number of messaging systems could increase the complexity of the solution.

A multitenant application can eventually adopt a hybrid approach, where core services use the same set of queues and topics in a single, shared messaging system, in order to implement internal, asynchronous communications. In contrast, other services could adopt a dedicated group of messaging entities or even a dedicated messaging system, for each tenant to mitigate the Noisy Neighbor issue and guarantee data isolation.

When deploying a messaging system to virtual machines, you should co-locate these virtual machines with the compute resources, to reduce the network latency. These virtual machines should not be shared with other services or applications, to avoid the messaging infrastructure to compete for the system resources, such as CPU, memory, and network bandwidth with other systems. Virtual machines can also spread across the availability zones, to increase the intra-region resiliency and reliability of business-critical workloads, including messaging systems. Suppose you decide to host a messaging system, such as RabbitMQ or Apache ActiveMQ, on virtual machines. In that case, we recommend deploying it to a virtual machine scale set and configuring it for autoscaling, based on metrics such as CPU or memory. This way, the number of agent nodes hosting the messaging system will properly scale out and scale in, based on traffic conditions. For more information, see Overview of autoscale with Azure virtual machine scale sets.

Likewise, when hosting your messaging system on a Kubernetes cluster, consider using node selectors and taints to schedule the execution of its pods on a dedicated node pool, not shared with other workloads, in order to avoid the Noisy Neighbor issue. When deploying a messaging system to a zone-redundant AKS cluster, use Pod topology spread constraints to control how pods are distributed across your AKS cluster among failure-domains, such as regions, availability zones, and nodes. When hosting a third-party messaging system on AKS, use Kubernetes autoscaling to dynamically scale out the number of worker nodes when the traffic increases. With Horizontal Pod Autoscaler and AKS cluster autoscaler, node and pod volumes get adjusted dynamically in real-time, to match the traffic condition and to avoid downtimes that are caused by capacity issues. For more information, see Automatically scale a cluster to meet application demands on Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS). Consider using Kubernetes Even-Driven Autoscaling (KEDA), if you want to scale out the number of pods of a Kubernetes-hosted messaging system, such as RabbitMQ or Apache ActiveMQ, based on the length of a given queue. With KEDA, you can drive the scaling of any container in Kubernetes, based on the number of events needing to be processed. For example, you can use KEDA to scale applications based on the length of an Azure Service Bus queue, of a RabbitMQ queue, or an ActiveMQ queue. For more information on KEDA, see Kubernetes Event-driven Autoscaling.

Isolation

When designing the messaging system for a multitenant solution, you should consider that different types of applications require a different kind of isolation, which is based on the tenants' performance, privacy, and auditing requirements.

- Multiple tenants can share the same messaging entities, such as queues, topics, and subscriptions, in the same messaging system. For example, a multitenant application could receive messages that carry data for multiple tenants, from a single Azure Service Bus queue. This solution can lead to performance and scalability issues. If some of the tenants generate a larger volume of orders than others, this could cause a backlog of messages. This problem, also known as the Noisy Neighbor issue, can degrade the service level agreement in terms of latency for some tenants. The problem is more evident if the consumer application reads and processes messages from the queue, one at a time, in a strict chronological order, and if the time necessary to process a message depends on the number of items in the payload. When sharing one or more queue resources across multiple tenants, the messaging infrastructure and processing systems should be able to accommodate the scale and throughput requirements-based expected traffic. This architectural approach is well-suited in those scenarios where a multitenant solution adopts a single pool of worker processes, in order to receive, process, and send messages for all the tenants.

- Multiple tenants share the same messaging system but use different topic or queue resources. This approach provides better isolation and data protection at a higher cost, increased operational complexity, and lower agility because system administrators have to provision, monitor, and maintain a higher number of queue resources. This solution ensures a consistent and predictable experience for all tenants, in terms of performance and service-level agreements, as it prevents any tenant from creating a bottleneck that can impact the other tenants.

- A separate, dedicated messaging system is used for each tenant. For example, a multitenant solution can use a distinct Azure Service Bus namespace for each tenant. This solution provides the maximum degree of isolation, at a higher complexity and operational cost. This approach guarantees consistent performance and allows for fine-tuning the messaging system, based on specific tenant needs. When a new tenant is onboarded, in addition to a fully dedicated messaging system, the provisioning application might also need to create a separate managed identity or a service principal with the proper RBAC permissions to access the newly created namespace. For example, when a Kubernetes cluster is shared by multiple instances of the same SaaS application, one for each tenant, and each running in a separate namespace, each application instance may use a different service principal or managed identity to access a dedicated messaging system. In this context, the messaging system could be a fully-managed PaaS service, such as an Azure Service Bus namespace, or a Kubernetes-hosted messaging system, such as RabbitMQ. When deleting a tenant from the system, the application should remove the messaging system and any dedicated resource that was priorly created for the tenant. The main disadvantage of this approach is that it increases operational complexity and reduces agility, especially when the number of tenants grows over time.

Review the following additional considerations and observations:

- If tenants need to use their own key to encrypt and decrypt messages, a multitenant solution should provide the option to adopt a separate Azure Service Bus Premium namespace for each tenant. For more information, see Configure customer-managed keys for encrypting Azure Service Bus data at rest.

- If tenants need a high level of resiliency and business continuity, a multitenant solution should provide the ability to provision a Service Bus Premium namespace with geo-disaster recovery and availability zones enabled. For more information, see Azure Service Bus Geo-disaster recovery.

- When using separate queue resources or a dedicated messaging system for each tenant, it's reasonable to adopt a separate pool of worker processes, for each of them to increase the data isolation level and reduce the complexity of dealing with multiple messaging entities. Each instance of the processing system could adopt different credentials, such as a connection string, a service principal, or a managed identity, in order to access the dedicated messaging system. This approach provides a better security level and isolation between tenants, but it requires an increased complexity in identity management.

Likewise, an event-driven application can provide different levels of isolation:

- An event-driven application receives events from multiple tenants, via a single, shared Azure Event Hubs instance. This solution provides a high level of agility, because onboarding a new tenant does not require creating a dedicated event-ingestion resource, but it provides a low data protection level, as it inter-mingles messages from multiple tenants in the same data structure.

- Tenants can opt for a dedicated event hub or Kafka topic to avoid the Noisy Neighbor issue and to meet their data isolation requirements, when events must not be co-mingled with those of other tenants, for security and data protection.

- If tenants need a high level of resiliency and business continuity, a multitenant should provide the ability to provision an Event Hubs Premium namespace, with geo-disaster recovery and availability zones enabled. For more information, see Azure Event Hubs - Geo-disaster recovery.

- Dedicated Event Hubs, with Event Hubs Capture enabled, should be created for those customers that need to archive events to an Azure Storage Account, for regulatory compliance reasons and obligations. For more information, see Capture events through Azure Event Hubs in Azure Blob Storage or Azure Data Lake Storage.

- A single multitenant application can send notifications to multiple internal and external systems, by using Azure Event Grid. In this case, a separate Event Grid subscription should be created for each consumer application. If your application makes use of multiple Event Grid instances to send notifications to a large number of external organizations, consider using event domains, which allow an application to publish events to thousands of topics, such as one for each tenant. For more information, see Understand event domains for managing Event Grid topics.

Complexity of implementation

When designing a multitenant solution, it's essential to consider how the system will evolve in the medium to long term, in order to prevent its complexity from growing over time, until it is necessary to redesign part of or the entire solution. This redesign will help you cope with an increasing number of tenants. When designing a messaging system, you should consider the expected growth in message volumes and tenants, in the next few years, and then create a system that can scale out, in order to keep up with the predicted traffic and to reduce the complexity of operations, such as provisioning, monitoring, and maintenance.

The solution should automatically create or delete the necessary messaging entities any time that a tenant application is provisioned or unprovisioned, without the need for manual operations.

A particular concern for multitenant data solutions is the level of customization that you support. Any customization should be automatically configured and applied by the application provisioning system (such as a DevOps system), which is based on a set of initial parameters, whenever a single-tenant or multitenant application is deployed.

Complexity of management and operations

Plan from the beginning how you intend to operate, monitor, and maintain your messaging and eventing infrastructure and how your multitenancy approach affects your operations and processes. For example, consider the following possibilities:

- You might plan to host the messaging system that's used by your application in a dedicated set of virtual machines, one for each tenant. If so, how do you plan to deploy, upgrade, monitor, and scale out these systems?

- Likewise, if you containerize and host your messaging system in a shared Kubernetes cluster, how do you plan to deploy, upgrade, monitor, and scale out individual messaging systems?

- Suppose you share a messaging system across multiple tenants. How can your solution collect and report the per-tenant usage metrics or throttle the number of messages that each tenant can send or receive?

- When your messaging system leverages a PaaS service, such as Azure Service Bus, you should ask the following question:

- How can you customize the pricing tier for each tenant, based on the features and isolation level (shared or dedicated) that are requested by the tenant?

- How can you create a per-tenant manage identity and Azure role assignment to assign the proper permissions only to the messaging entities, such as queues, topics, and subscriptions, that the tenant can access? For more information, see Authenticate a managed identity with Microsoft Entra ID to access Azure Service Bus resources.

- How will you migrate tenants, if they need to move to a different type of messaging service, a different deployment, or another region?

Cost

Generally, the higher the density of tenants to your deployment infrastructure, the lower the cost to provision that infrastructure. However, shared infrastructure increases the likelihood of issues like the Noisy Neighbor issue, so consider the tradeoffs carefully.

Approaches and patterns to consider

Several Cloud Design Patterns from the Azure Architecture Center can be applied to a multitenant messaging system. You might choose to follow one or more patterns consistently, or you could consider mixing and matching patterns, based on your needs. For example, you might use a multitenant Service Bus namespace for most of your tenants, but then you might deploy a dedicated, single-tenant Service Bus namespace for those tenants who pay more or who have higher requirements, in terms or isolation and performance. Similarly, it's often a good practice to scale by using deployment stamps, even when you use a multitenant Service Bus namespace or dedicated namespaces within a stamp.

Deployment Stamps pattern

For more information about the Deployment Stamps pattern and multitenancy, see the Deployment Stamps pattern section of Architectural approaches for multitenancy. For more information about tenancy models, see Tenancy models to consider for a multitenant solution.

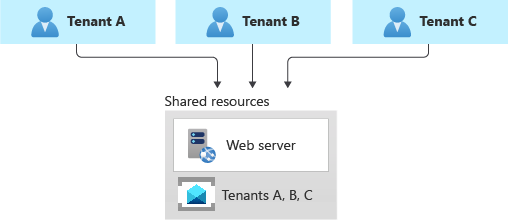

Shared messaging system

You might consider deploying a shared messaging system, such as Azure Service Bus, and sharing it across all of your tenants.

This approach provides the highest density of tenants to the infrastructure, so it reduces the overall total cost of ownership. It also often reduces the management overhead, since there's a single messaging system or resource to manage and secure.

However, when you share a resource or an entire infrastructure across multiple tenants, consider the following caveats:

- Always keep in mind and consider the constraints, scaling capabilities, quotas, and limits of the resource in question. For example, the maximum number of Service Bus namespaces in an Azure subscription, the maximum number of Event Hubs in a single namespace, or the maximum throughput limits, might eventually become a hard blocker, if and when your architecture grows to support more tenants. Carefully consider the maximum scale that you need to achieve in terms of the number of namespaces per single Azure subscription, or queues per single namespace. Then compare your current and future estimates to the existing quotas and limits of the messaging system of choice, before you select this pattern.

- As mentioned in the above sections, the Noisy Neighbor problem might become a factor, when you share a resource across multiple tenants, especially if some are particularly busy or if they generate higher traffic than others. In this case, consider applying the Throttling pattern or the Rate Limiting pattern to mitigate these effects. For example, you could limit the maximum number of messages that a single tenant can send or receive in the unit of time.

- You might have difficulty monitoring the activity and measuring the resource consumption for a single tenant. Some services, such as Azure Service Bus, charge for messaging operations. Hence, when you share a namespace across multiple tenants, your application should be able to keep track of the number of messaging operations done on behalf of each tenant and the chargeback costs to them. Other services don't provide the same level of detail.

Tenants may have different requirements for security, intra-region resiliency, disaster recovery, or location. If these don't match your messaging system configuration, you might not be able to accommodate them just with a single resource.

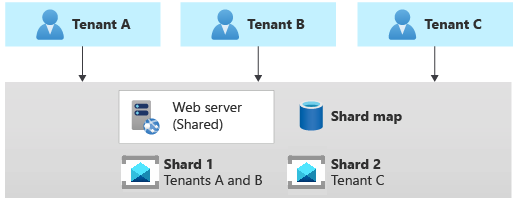

Sharding pattern

The Sharding pattern involves deploying multiple messaging systems, called shards, which contain one or more tenants' messaging entities, such as queues and topics. Unlike deployment stamps, shards don't imply that the entire infrastructure is duplicated. You might shard messaging systems without also duplicating or sharding other infrastructure in your solution.

Every messaging system or shard can have different characteristics in terms of reliability, SKU, and location. For example, you could shard your tenants across multiple messaging systems with different characteristics, based on their location or needs in terms of performance, reliability, data protection, or business continuity.

When using the sharding pattern, you need to use a sharding strategy, in order to map a given tenant to the messaging system that contains its queues. The lookup strategy uses a map to individuate the target messaging system, based on the tenant name or ID. Multiple tenants might share the same shard, but the messaging entities used by a single tenant won't be spread across multiple shards. The map can be implemented with a single dictionary that maps the tenant's name to the name or reference of the target messaging system. The map can be stored in a distributed cache accessible, by all the instances of a multitenant application, or in a persistent store, such as a table in a relational database or a table in a storage account.

The Sharding pattern can scale to very large numbers of tenants. Additionally, depending on your workload, you might be able to achieve a high density of tenants to shards, so the cost can be attractive. The Sharding pattern can also be used to address Azure subscription and service quotas, limits, and constraints.

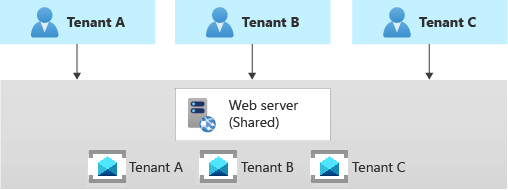

Multitenant app with dedicated messaging system for each tenant

Another common approach is to deploy a single multitenant application, with dedicated messaging systems for each tenant. In this tenancy model, you have some shared components, such as computing resources, while other services are provisioned, and managed using a single-tenant, dedicated deployment approach. For example, you could build a single application tier, and then deploy individual messaging systems for each tenant, as shown in the following illustration.

Horizontally partitioned deployments can help you mitigate a noisy-neighbor problem, if you've identified that most of the load on your system is due to specific components that you can deploy separately for each tenant. For example, you may need to use a separate messaging or event streaming system for each tenant because a single instance is not enough to keep up with traffic that's generated by multiple tenants. When using a dedicated messaging system for each tenant, if a single tenant causes a large volume of messages or events, this might affect the shared components but not other tenants' messaging systems.

Because you provision dedicated resources for each tenant, the cost for this approach can be higher than a shared hosting model. On the other hand, it's easier to charge back resource costs of a dedicated system to the unique tenant that makes use of it, when adopting this tenancy model. This approach allows you to achieve high density for other services, such as computing resources, and it reduces these components' costs.

With a horizontally partitioned deployment, you need to adopt an automated process for deploying and managing a multitenant application's services, especially those used by a single tenant.

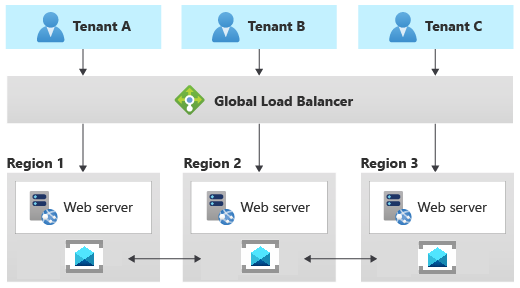

Geodes pattern

The Geode pattern involves deploying a collection of backend services into a set of geographical nodes. Each can service any request for any client in any region. This pattern allows you to serve requests in an active-active style, which improves latency and increases availability, by distributing request processing around the globe.

Azure Service Bus and Azure Event Hubs support metadata disaster recovery, across primary and secondary disaster recovery namespaces and across separate regions and availability zones, in order to provide support for the best intra-region resiliency. Also, Azure Service Bus and Azure Event Hubs implement a set of federation patterns that actively replicate the same logical topic, queue, or event hub to be available in multiple namespaces, eventually located in different regions. For more information, see the following resources:

- Message replication and cross-region federation

- Message replication tasks patterns

- Multi-site and multi-region federation

- Event replication tasks patterns

Contributors

This article is maintained by Microsoft. It was originally written by the following contributors.

Principal author:

- Paolo Salvatori | Principal Customer Engineer, FastTrack for Azure

Other contributors:

- John Downs | Principal Software Engineer

- Clemens Vasters | Principal Architect, Messaging Services and Standards

- Arsen Vladimirskiy | Principal Customer Engineer, FastTrack for Azure

Next steps

For more information about messaging design patterns, see the following resources: