What are business continuity, high availability, and disaster recovery?

This article defines and describes business continuity and business continuity planning in terms of risk management through high availability and disaster recovery design. While this article doesn't provide explicit guidance about how to meet your own business continuity needs, it helps you to understand the concepts that are used throughout Microsoft's reliability guidance.

Business continuity is the state in which a business can continue operations during failures, outages, or disasters. Business continuity requires proactive planning, preparation, and the implementation of resilient systems and processes.

Planning for business continuity requires identifying, understanding, classifying, and managing risks. Based on the risks and their likelihoods, design for both high availability (HA) and disaster recovery (DR).

High availability is about designing a solution to be resilient to day-to-day issues and to meet the business needs for availability.

Disaster recovery is about planning how to deal with uncommon risks and the catastrophic outages that can result.

Business continuity

In general, cloud solutions are tied directly to business operations. Whenever a cloud solution is unavailable or experiences a serious problem, the impact on business operations can be severe. A severe impact can break business continuity.

Severe impacts on business continuity can include:

- Loss of business income.

- The inability to provide an important service to users.

- Breach of a commitment that's been made to a customer or another party.

It's important to understand and communicate the business expectations, and the consequences of failures, to important stakeholders including those who design, implement, and operate the workload. Those stakeholders then respond by sharing the costs involved in meeting that vision. There's typically a process of negotiation and revisions of that vision based on budget and other constraints.

Business continuity planning

To control or completely avoid a negative impact on business continuity, it's important to proactively create a business continuity plan. A business continuity plan is based on risk assessment and developing methods of controlling those risks through various approaches. The specific risks and approaches to mitigate vary for each organization and workload.

A business continuity plan doesn't only take into consideration the resiliency features of the cloud platform itself but also the features of the application. A robust business continuity plan also incorporates all aspects of support in the business including people, business-related manual or automated processes, and other technologies.

Business continuity planning should include the following sequential steps:

Risk identification. Identify risks to a workload's availability or functionality. Possible risks could be network issues, hardware failures, human error, region outage, etc. Understand the impact of each risk.

Risk classification. Classify each risk as either a common risk, which should be factored into plans for HA, or an uncommon risk, which should be part of DR planning.

Risk mitigation. Design mitigation strategies for HA or DR to minimize or mitigate risks such as by using redundancy, replication, failover, and backups. Also, consider nontechnical and process-based mitigations and controls.

Business continuity planning is a process, not a one-time event. Any business continuity plan that is created should be reviewed and updated regularly to ensure that it remains relevant and effective, and that it supports current business needs.

Risk identification

The initial phase in business continuity planning is to identify risks to a workload's availability or functionality. Each risk should be analyzed to understand its likelihood and its severity. Severity needs to include any potential downtime or data loss, as well as whether any aspects of the rest of the solution design might compensate for negative effects.

The following table is a non-exhaustive list of risks, ordered by decreasing likelihood:

| Example risk | Description | Regularity (likelihood) |

|---|---|---|

| Transient network issue | A temporary failure in a component of the networking stack, which is recoverable after a short time (usually a few seconds or less). | Regular |

| Virtual machine reboot | A reboot of a virtual machine that you use, or that a dependent service uses. Reboots might occur because the virtual machine crashes or needs to apply a patch. | Regular |

| Hardware failure | A failure of a component within a datacenter, such as a hardware node, rack, or cluster. | Occasional |

| Datacenter outage | An outage that affects most or all of a datacenter, such as a power failure, network connectivity problem, or issues with heating and cooling. | Unusual |

| Region outage | An outage that affects an entire metropolitan area or wider area, such as a major natural disaster. | Very unusual |

Business continuity planning isn't just about the cloud platform and infrastructure. It's important to consider the risk of human errors. Furthermore, some risks that might traditionally be considered security, performance, or operational risks should also be considered reliability risks because they affect the solution's availability.

Here are some examples:

| Example risk | Description |

|---|---|

| Data loss or corruption | Data has been deleted, overwritten, or otherwise corrupted by an accident, or from a security breach like a ransomware attack. |

| Software bug | A deployment of new or updated code introduces a bug that impacts availability or integrity, leaving the workload in a malfunctioning state. |

| Failed deployments | A deployment of a new component or version has failed, leaving the solution in an inconsistent state. |

| Denial of service attacks | The system has been attacked in an attempt to prevent legitimate use of the solution. |

| Rogue administrators | A user with administrative privileges has intentionally performed a damaging action against the system. |

| Unexpected influx of traffic to an application | A spike in traffic has overwhelmed the system's resources. |

Failure mode analysis (FMA) is the process of identifying potential ways in which a workload or its components could fail, and how the solution behaves under those situations. To learn more, see Recommendations for performing failure mode analysis.

Risk classification

Business continuity plans must address both common and uncommon risks.

Common risks are planned and expected. For example, in a cloud environment it's common for there to be transient failures including brief network outages, equipment restarts due to patches, timeouts when a service is busy, and so forth. Because these events happen regularly, workloads need to be resilient to them.

A high availability strategy must consider and control for each risk of this type.

Uncommon risks are generally the result of an unforeseeable event, such as a natural disaster or major network attack, that can lead to a catastrophic outage.

Disaster recovery processes deal with these rare risks.

High availability and disaster recovery are interrelated, and so it's important to plan strategies for both of them together.

It's important to understand that risk classification depends on workload architecture and the business requirements, and some risks can be classified as HA for one workload and DR for another workload. For example, a full Azure region outage would generally be considered a DR risk to workloads in that region. But for workloads that use multiple Azure regions in an active-active configuration with full replication, redundancy, and automatic region failover, a region outage is classified as an HA risk.

Risk mitigation

Risk mitigation consists of developing strategies for HA or DR to minimize or mitigate risks to business continuity. Risk mitigation can be technology-based or human-based.

Technology-based risk mitigation

Technology-based risk mitigation uses risk controls that are based on how the workload is implemented and configured, such as:

- Redundancy

- Data replication

- Failover

- Backups

Technology-based risk controls must be considered inside the context of the business continuity plan.

For example:

Low-downtime requirements. Some business continuity plans are not able to tolerate any form of downtime risk due to stringent high availability requirements. There are certain technology-based controls that may require time for a human to be notified and then to respond. Technology-based risk controls that include slow manual processes are likely to be unfit for inclusion in their risk mitigation strategy.

Tolerance to partial failure. Some business continuity plans are able to tolerate a workflow that runs in a degraded state. When a solution operates in a degraded state, some components might be disabled or nonfunctional, but core business operations can continue to be performed. To learn more, see Recommendations for self-healing and self-preservation.

Human-based risk mitigation

Human-based risk mitigation uses risk controls that are based on business processes, such as:

- Triggering a response playbook.

- Falling back to manual operations.

- Training and cultural changes.

Important

Individuals designing, implementing, operating, and evolving the workload should be competent, encouraged to speak up if they have concerns, and feel a sense of responsibility for the system.

Because human-based risk controls are often slower than technology-based controls, and more prone to human error, a good business continuity plan should include a formal change control process for anything that would alter the state of the running system. For example, consider implementing the following processes:

- Rigorously test your workloads in accordance with workload criticality. To prevent change-related issues, make sure to test any changes that are made to the workload.

- Introduce strategic quality gates as part of your workload's safe deployment practices. To learn more, see Recommendations for safe deployment practices.

- Formalize procedures for ad-hoc production access and data manipulation. These activities, no matter how minor, can present a high risk of causing reliability incidents. Procedures might include pairing with another engineer, using checklists, and getting peer reviews before executing scripts or applying changes.

High availability

High availability is the state in which a specific workload can maintain its necessary level of uptime on a day-to-day basis, even during transient faults and intermittent failures. Because these events happen regularly, it's important that each workload is designed and configured for high availability in accordance with the requirements of the specific application and customer expectations. The HA of each workload contributes to your business continuity plan.

Because HA can vary with each workload, it's important to understand the requirements and customer expectations when determining high availability. For example, an application that your organization uses to order office supplies might require a relatively low level of uptime, while a critical financial application might require a much higher uptime. Even within a workload, different flows might have different requirements. For example, in an eCommerce application, flows that support customers browsing and placing orders might be more important than order fulfillment and back-office processing flows. To learn more about flows, see Recommendations for identifying and rating flows.

Commonly, uptime is measured based on the number of "nines" in the uptime percentage. The uptime percentage relates to how much downtime you're allowing for over a given period of time. Here are some examples:

- A 99.9% uptime requirement (three nines) allows for approximately 43 minutes of downtime in a month.

- A 99.95% uptime requirement (three and a half nines) allows for approximately 21 minutes of downtime in a month.

The higher the uptime requirement, the less tolerance you have for outages, and the more work you have to do to reach that level of availability. Uptime isn't measured by the uptime of a single component like a node, but by the overall availability of the entire workload.

Important

Don't overengineer your solution to reach higher levels of reliability than are justified. Use business requirements to guide your decisions.

High availability design elements

To achieve HA requirements, a workload can include a number of design elements. Some of the common elements are listed and described below in this section.

Note

Some workloads are mission-critical, which means any downtime can have severe consequences to human life and safety, or major financial losses. If you're designing a mission-critical workload, there are specific things you need to think about when you design your solution and manage your business continuity. For more information, see the Azure Well-Architected Framework: Mission-critical workloads.

Azure services and tiers that support high availability

Many Azure services are designed to be highly available, and can be used to build highly available workloads. Here are some examples:

- Azure Virtual Machine Scale Sets provide high availability for virtual machines (VMs) by automatically creating and managing VM instances and distributing those VM instances to reduce the impact of infrastructure failures.

- Azure App Service provides high availability through a variety of approaches, including automatically moving workers from an unhealthy node to a healthy node, and by providing capabilities for self-healing from many common fault types.

Use each service reliability guide to understand the capabilities of the service, decide which tiers to use, and determine which capabilities to include in your high availability strategy.

Review the service level agreements (SLAs) for each service to understand the expected levels of availability and the conditions you need to meet. You might need to select or avoid specific tiers of services to achieve certain levels of availability. Some services from Microsoft are offered with the understanding that no SLA is provided, such as development or basic tiers, or that the resource could be reclaimed from your running system, such as spot-based offerings. Also, some tiers have added reliability features, such as support for availability zones.

Fault tolerance

Fault tolerance is the ability of a system to continue operating, in some defined capacity, in the event of a failure. For example, a web application might be designed to continue operating even if a single web server fails. Fault tolerance can be achieved through redundancy, failover, partitioning, graceful degradation, and other techniques.

Fault tolerance also requires that your applications handle transient faults. When you build your own code, you might need to enable transient fault handling yourself. Some Azure services provide built-in transient fault handling for some situations. For example, by default Azure Logic Apps automatically retries failed requests to other services. To learn more, see Recommendations for handling transient faults.

Redundancy

Redundancy is the practice of duplicating instances or data to increase the reliability of the workload.

Redundancy can be achieved by distributing replicas or redundant instances in one more all of the following ways:

- Inside a datacenter (local redundancy)

- Between availability zones within a region (zone redundancy)

- Across regions (geo-redundancy).

Here are some of examples of how some Azure services provide redundancy options:

- Azure App Service enables you to run multiple instances of your application, to ensure that the application remains available even if one instance fails. If you enable zone redundancy, those instances are spread across multiple availability zones in the Azure region you use.

- Azure Storage provides high availability by automatically replicating data at least three times. You can distribute those replicas across availability zones by enabling zone-redundant storage (ZRS), and in many regions you can also replicate your storage data across regions by using geo-redundant storage (GRS).

- Azure SQL Database has multiple replicas to ensure that the data remains available even if one replica fails.

To learn more about how redundancy works, see Redundancy, replication, and backup. To learn about how to apply redundancy in your solution, see Recommendations for designing for redundancy and Recommendations for using availability zones and regions.

Scalability and elasticity

Scalability and elasticity are the abilities of a system to handle increased load by adding and removing resources (scalability), and to do so quickly as your requirements change (elasticity). Scalability and elasticity can help a system maintain availability during peak loads.

Many Azure services support scalability. Here are some examples:

- Azure Virtual Machine Scale Sets, Azure API Management, and several other services support Azure Monitor autoscale. With Azure Monitor autoscale, you can specify policies like "when my CPU consistently goes above 80%, add another instance".

- Azure Functions can dynamically provision instances to serve your requests.

- Azure Cosmos DB supports autoscale throughput, where the service can automatically manage the resources assigned to your databases based on policies you specify.

Scalability is a key factor to consider during partial or complete malfunction. If a replica or compute instance is unavailable, the remaining components might need to bear more load to handle the load that was previously being handled by the faulted node. Consider overprovisioning if your system can't scale quickly enough to handle your expected changes in load.

For more information on how to design a scalable and elastic system, see Recommendations for designing a reliable scaling strategy.

Zero-downtime deployment techniques

Deployments and other system changes introduce a significant risk of downtime. Because downtime risk is a challenge to high availability requirements, it's important to use zero-downtime deployment practices to make updates and configuration changes without any required downtime.

Zero-downtime deployment techniques can include:

- Updating a subset of your resources at a time.

- Controlling the amount of traffic that reaches the new deployment.

- Monitoring for any impact to your users or system.

- Rapidly remediating the issue, such as by rolling back to a previous known-good deployment.

To learn more about zero-downtime deployment techniques, see Safe deployment practices.

Azure itself uses zero-downtime deployment approaches for our own services. When you build your own applications, you can adopt zero-downtime deployments through a variety of approaches, such as:

- Azure Container Apps provides multiple revisions of your application, which can be used to achieve zero-downtime deployments.

- Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) supports a variety of zero-downtime deployment techniques.

While zero-downtime deployments are often associated with application deployments, they should also be used for configuration changes. Here are some ways you can apply configuration changes safely:

- Azure Storage lets you change your storage account access keys in multiple stages, which prevents downtime during key rotation operations.

- Azure App Configuration provides feature flags, snapshots, and other capabilities to help you to control how configuration changes are applied.

If you decide not to implement zero-downtime deployments, make sure that you define maintenance windows so that you can make system changes at a time when your users expect it.

Automated testing

It's important to test your solution's ability to withstand the outages and failures that you consider to be in scope for HA. Many of these failures can be simulated in test environments. Testing your solution's ability to automatically tolerate or recover from a variety of fault types is called chaos engineering. Chaos engineering is critical for mature organizations with stringent standards for HA. Azure Chaos Studio is a chaos engineering tool that can simulate some common fault types.

To learn more, see Recommendations for designing a reliability testing strategy.

Monitoring and alerting

Monitoring lets you know the health of your system, even when automated mitigations take place. Monitoring is critical for understanding how your solution is behaving, and to watch for early signals of failures like increased error rates or high resource consumption. With alerts, you can proactively receive important changes in your environment.

Azure provides a variety of monitoring and alerting capabilities, including the following:

- Azure Monitor collects logs and metrics from Azure resources and applications, and it can send alerts and display data in dashboards.

- Azure Monitor Application Insights provides detailed monitoring of your applications.

- Azure Service Health and Azure Resource Health monitor the health of the Azure platform and your resources.

- Scheduled Events advise when maintenance is planned for virtual machines.

For more information, see Recommendations for designing a reliable monitoring and alerting strategy.

Disaster recovery

A disaster is a distinct, uncommon, major event that has a larger and longer-lasting impact than an application can mitigate through the high availability aspect of its design. Examples of disasters include:

- Natural disasters, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, or fires.

- Human errors that result in a major impact, such as accidentally deleting production data, or a misconfigured firewall that exposes sensitive data.

- Major security incidents, like denial of service or ransomware attacks that lead to data corruption, data loss, or service outages.

Disaster recovery is about planning how you respond to these types of situations.

Note

You should follow recommended practices across your solution to minimize the likelihood of these events. However, even after careful proactive planning, it's prudent to plan how you would respond to these situations if they arise.

Disaster recovery requirements

Due to the rarity and severity of disaster events, DR planning brings different expectations for your response. Many organizations accept the fact that, in a disaster scenario, some level of downtime or data loss is unavoidable. A complete DR plan must specify the following critical business requirements for each flow:

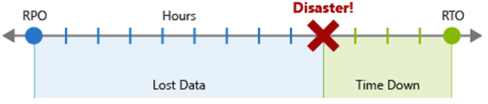

Recovery Point Objective (RPO) is the maximum duration of acceptable data loss in the event of a disaster. RPO is measured in units of time, such as "30 minutes of data" or "four hours of data."

Recovery Time Objective (RTO) is the maximum duration of acceptable downtime in the event of a disaster, where "downtime" is defined by your specification. RTO is also measured in units of time, like "eight hours of downtime."

Each component or flow in the workload might have individual RPO and RTO values. Examine disaster-scenario risks and potential recovery strategies when deciding on the requirements. The process of specifying an RPO and RTO effectively creates DR requirements for your workload as a result of your unique business concerns (costs, impact, data loss, etc.).

Note

While it's tempting to aim for an RTO and RPO of zero (no downtime and no data loss in the event of a disaster), in practice it's difficult and costly to implement. It's important for technical and business stakeholders to discuss these requirements together and decide on realistic requirements. For more information, see Recommendations for defining reliability targets.

Disaster recovery plans

Regardless of the cause of the disaster, it's important that you create a well-defined and testable DR plan. That plan will be used as part of infrastructure and application design to actively support it. You might create multiple DR plans for different types of situations. DR plans often rely on process controls and manual intervention.

DR isn't an automatic feature of Azure. However, many services do provide features and capabilities that you can use to support your DR strategies. You should review the reliability guides for each Azure service to understand how the service works and its capabilities, and then map those capabilities to your DR plan.

The following sections list some common elements of a disaster recovery plan, and describe how Azure can help you to achieve them.

Failover and failback

Some disaster recovery plans involve provisioning a secondary deployment in another location. If a disaster affects the primary deployment of the solution, traffic can then be failed over to the other site. Failover requires careful planning and implementation. Azure provides a variety of services to assist with failover, such as:

- Azure Site Recovery provides automated failover for on-premises environments and virtual machine-hosted solutions in Azure.

- Azure Front Door and Azure Traffic Manager support automated failover of incoming traffic between different deployments of your solution, such as in different regions.

It usually takes some time for a failover process to detect that the primary instance has failed and to switch to the secondary instance. Make sure that the RTO of the workload is aligned with the failover time.

It's also important to consider failback, which is the process by which you restore operations in the primary region after it's recovered. Failback can be complex to plan and implement. For example, data in the primary region may have been written after failover begins. You'll need to make careful business decisions on how you handle that data.

For more information, see Failover and failback.

Backups

Backups involve taking a copy of your data and storing it safely for a defined period of time. With backups you can recover from disasters when automatic failover to another replica isn't possible, or when data corruption has occurred.

When using backups as part of a disaster recovery plan it's important to take the following into consideration:

Storage location. When you use backups as part of a disaster recovery plan, they should be stored separately to the main data. Typically backups are stored in another Azure region.

Data loss. Because backups are typically taken infrequently, backup restoration usually involves data loss. For this reason, backup recovery should be used as a last resort and a disaster recovery plan should specify the sequence of steps and recovery attempts that must take place before restoring from a backup. It's important to make sure that the workload RPO is aligned with the backup interval.

Recovery time. Backup restoration often takes time, so it's critical to test your backups and restoration processes to verify their integrity and understand how long the restoration process takes. Make sure that the workload's RTO accounts for the time it takes to restore your backup.

Many Azure data and storage services support backups, such as the following:

- Azure Backup provides automated backups for virtual machine disks, storage accounts, AKS, and a variety of other sources.

- Many Azure database services, including Azure SQL Database and Azure Cosmos DB, have an automated backup capability for your databases.

- Azure Key Vault provides features to back up your secrets, certificates, and keys.

Automated deployments

To rapidly deploy and configure required resources in the event of a disaster, use Infrastructure as code (IaC) assets, such as Bicep files, ARM templates, or Terraform configuration file. Using IaC reduces your recovery time and potential for error, compared to manually deploying and configuring resources.

Testing and drills

It's critical to routinely validate and test your DR plans, as well as your wider reliability strategy. Include all of the human processes in your drills, and don't just focus on the technical processes.

If you haven't tested your recovery processes in a disaster simulation, you're more likely to face major problems when using them in an actual disaster. Also, by testing your DR plans and required processes, you can validate the feasibility of your RTO.

To learn more, see Recommendations for designing a reliability testing strategy.

Related content

- Use the Azure service reliability guides to understand how each Azure service supports reliability in its design, and to learn about the capabilities you can build into your HA and DR plans.

- Use the Azure Well-Architected Framework: Reliability pillar to learn more about how to design a reliable workload on Azure.

- Use the Well-Architected Framework perspective on Azure services to learn more about how to configure each Azure service to meet your requirements for reliability and across the other pillars of the Well-Architected Framework.

- To learn more about disaster recovery planning, see Recommendations for designing a disaster recovery strategy.