An alternative to ConfigureAwait(false) everywhere

One of the general recommendations you may often read is to use ConfigureAwait(false) in library code. This is so that when the library is used, it does not block the synchronization context in use by the application (e.g. the UI thread). If the library doesn’t know anything about the app, it doesn’t depend on the application’s context and doesn’t need to run within it. This makes sense but it ends up truly meaning that you have to put ConfigureAwait(false) on every async call in your entire library. To me, that seems ...excessive.

As I see it, If you are using ConfigureAwait(), you probably really care about it and want it to actually work. Unfortunately, because async methods might actually complete synchronously, the call to ConfigureAwait() might not affect anything. That means you have to put it on the next async call too, and so on, until it is on every single method in your library.

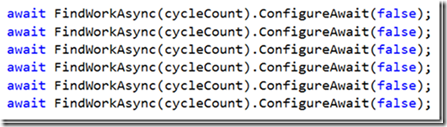

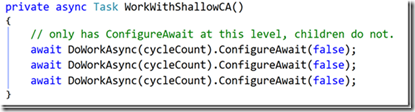

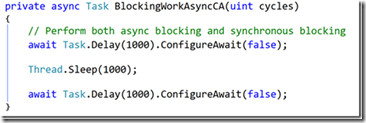

Tagging every single call with a decorator method has always bothered me as inelegant and it clutters my code. It’s also something that can easily be forgotten when updating or adding new code. But there is also another more hidden potential issue – the first async call tree. The first time you attempt to await an async method, it doesn’t get the benefit of ConfigureAwait(false). Look at this code

The first call to FindWorkAsync() has to run before we get a Task to configure. That means that everything that happens inside the first call happens on our caller’s context. That means if any long running actions happen in FindWorkAsync() or in its children, it may affect the callers context.

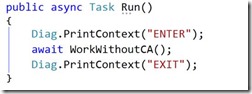

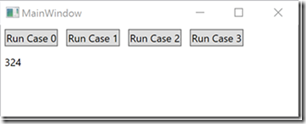

This behavior can be seen by running this sample WPF application

The number on this form is updated by a DispatchTimer every 100ms. DispatchTimers run on the UI thread. If anything blocks the UI thread, you will see that timer pause. In addition, all the buttons are disabled while the work is being done so there is a good visual indicator of when the work is finally finished (the buttons become enabled again).

Using this app, lets look at a couple of scenarios and see how the it behaves...

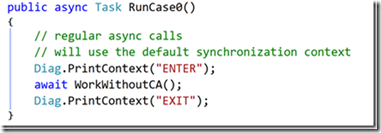

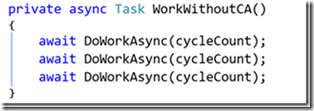

Regular async/await

“Run Case 0” runs a regular set of async/await calls without the use of ConfigureAwait(). This is the basic async/await code as it is usually implemented.

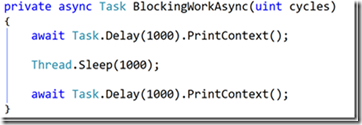

The whole operation takes a few seconds. While this is running, the UI periodically freezes because WorkWithoutCA() calls BlockingWorkAsync() which calls Thread.Sleep(1000). During this sleep time, the timer doesn’t change. The behavior looks like this:

- Buttons disabled

- UI freezes for 1 second periodically when BlockingWorkAsync() blocks synchronously on Thread.Sleep

- Buttons enabled

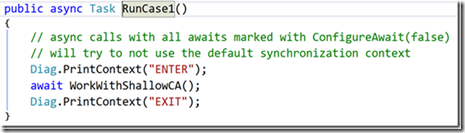

Shallow coverage with ConfigureAwait(false)

“Run Case 1” runs the same sequence of async/await calls, except that some calls to ConfigureAwait(false) have been added to the entry of the library’s API. The ConfigureAwait(false) calls are only at the top level of our process. The lower level methods DoWorkAsync() and BlockingWorkAsync() are unchanged.

When this runs, you will notice that the UI freezes for a short time just once. That is the first call to DoWorkAsync() which is still running on the UI thread. The 2nd and 3rd calls to DoWorkAsync() are not on the UI thread and so don’t freeze the UI

- Buttons disabled

- UI freezes once for 1 second during the first DoWorkAsync() call

- UI unfrozen for subsequent calls to DoWorkAsync()

- Buttons enabled

It’s this 2nd step that I’m concerned with in this discussion. Obviously the overall behavior is much better because in this case the UI is unfrozen for a majority of the time. But if we are concerned about this at all, why aren’t we concerned about eliminating it completely? I want to push that behavior across all of my library’s functionality, not just stuff that happens after the first await.

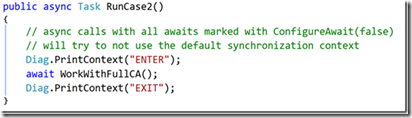

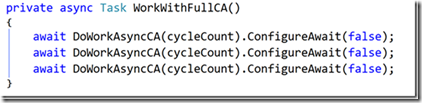

Full coverage with ConfigureAwait(false)

“Run Case 2” solves this in the way that is typically recommended. You push ConfigureAwait() all the way down the call tree.

…

The behavior is now as we desire it to be – no blocking the UI during any of the calls.

- Buttons disabled

- UI unfrozen for all calls to DoWorkAsync()

- Buttons enabled

The main problem with this approach is that now we have a maintenance issue. Every new await needs to have ConfigureAwait(false) put on it – just in case. It also tends to clutter the code since this one thing is now everywhere. As a matter of style it makes the code less readable.

So I am proposing an alternative…

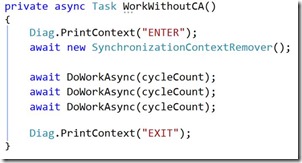

Going manual without ConfigureAwait(false)

“Run Case 3”

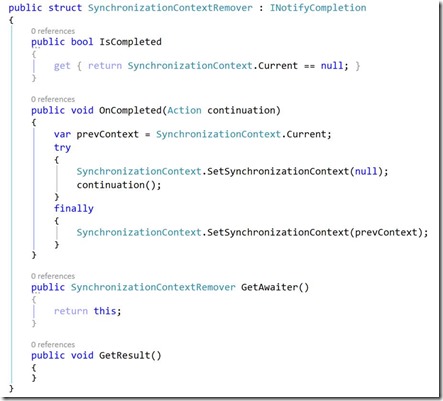

What if we did what ConfigureAwait() does for us, but we do it once at the beginning of our callstack and didn’t have to think about it again? Unfortunately, that means not using a fluent API. The fluent API of ConfigureAwait() is the reason for the “first call” problem. The snippet of code below does not use ConfigureAwait(), but uses a helper object to temporarily remove the SynchronizationContext manually (and restores it before returning to the caller).

This gives us the same behavior as Case 2 but the code is cleaner. With this technique, I no longer have to remember to put ConfigureAwait(false) all over my code which makes it easier to maintain and to read. The only thing I need to do is insert a single await on the helper object at the beginning of my public APIs and all its children will get called on the default context automatically with no changes to them at all.

Additional notes

- The sample is available on my github repo. That code uses some extra methods which I’ve removed in the snippets above. Those methods just print some diagnostic info out so that you can look at the debug output and see the context flowing or not existing at all the various points in the app. It also contains a Case 4 which uses Task.Run to invoke the method instead of the Case 3 wrapper. These two cases are very similar but when Task.Run is used, the method gets queued to the thread pool and will start at some later point in time. Case 3 will initiate the asynchronous method immediately.

- I am not advocating never using ConfigAwait(false). I’ve had very good success using it in specific targeted scenarios when we knew where the problem was and where to put ConfigureAwait(false) to resolve that problem. I am suggesting that it’s not a cure all and that blanketed use of ConfigAwait is not a good practice.

- I’m also open to other suggestions. After discussing this with others and looking at a few different options (one of them is in the Github history of case 3), this seems the most reasonable so far.

- This sample is a WPF application because its easiest to visualize for demo purposes, but the concept is applicable to any .NET library with async code whether running on the client, on a server, or in the cloud.

If you have anything to add or suggest, please leave a comment below.

Comments

- Anonymous

February 07, 2017

Very interesting!Minor improvement: Since there's no per-instance state, you could make it a singleton and avoid a bit of garbage.I recently added a NoContext wrapper to my AsyncEx library: https://github.com/StephenCleary/AsyncEx/blob/master/src/Nito.AsyncEx.Tasks/SynchronizationContextSwitcher.cs#L36It has a similar goal, but NoContext requires the code without context to be passed as a lambda. So the code structure ends up being "the code in this block executes without context" instead of "the code after this statement executes without context".Have you forgotten to push to your repo? I'm not seeing SynchronizationContextRemover there.- Anonymous

February 07, 2017

The comment has been removed - Anonymous

October 16, 2017

The NoContext wrapper does not help prevent deadlocks if used inside the public methods of an async library, as the original context is still restored upon exiting the method (so if the caller calls Wait() on the async method, it will deadlock in ASP.NET or a GUI). It is however helpful on the library consumer side to drop context before calling the library.- Anonymous

October 20, 2017

If the caller to a method uses this technique (or the ConfigAwait everywhere) it will prevent deadlocks even if the caller calls Wait(). But if they call Wait() they will block until the entire method is finished thereby appearing like normal synchronous method. If you alter the Run methods of either Case 2 or Case 3 from "await WorkWithFullCA();" to " WorkWithFullCA().Wait();" you will see that the UI completely freezes for a while, and then resumes.- Anonymous

October 20, 2017

I was Actually referring to the NoContext wrapper from Stephen Cleary, which is not really equivalent in usage to your SynchronizationContextRemover. Your SynchronizationContextRemover is perfect for use inside a library's public method, while Stephen's lambda wrapper is helpful when calling a library which may not remove context and therefore could cause deadlocks when waiting for it from an ASP.NET or GUI program.- Anonymous

October 20, 2017

Sorry, I misread that. Thanks for the clarification.

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

February 07, 2017

When the original Async CTP shipped, there were a handful of "convenience await" systems that could be used to jump contexts. E.g., you could await a SynchronizationContext (or TaskScheduler) to "jump" to that thread for the remainder of the method.However, these were removed before release because it becomes difficult to know what context you're in when you enter the catch/finally block. E.g.:try{ // Code that may throw (1) await SynchronizationContextRemover.Instance; // Code that may throw (2)}catch (Exception){ // What is the current SyncCtx here?}- Anonymous

February 07, 2017

a quick test shows the context is still null until the method exits for #2. I'd argue #1 is a misuse of the technique and that this should only be used only as the beginning of a method (and outside of any try/catch block). Maybe I'll add code analysis rule to the solution.

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

February 09, 2017

Shouldn't IsCompleted remain forever true once it is ever been true?- Anonymous

March 01, 2017

IsCompleted is called by the await infrastructure in order to determine if the async task is already completed. If it is already completed, it just continues normally and doesn't do any awaiting. So we really just need it to be false that first time so that we do drop into the await workflow. It doesn't get called after that in this scenario.

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

March 23, 2017

Could I suggest a small opt? You can check for null in the current ctx and if it is null, you can skip the try/finally... so addingif (prevContext == null){ continuation(); return;}before the var prevContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;- Anonymous

March 23, 2017

good point!- Anonymous

November 21, 2018

The comment has been removed

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

March 23, 2017

The comment has been removed- Anonymous

March 23, 2017

Excellent!, thanks for checking out!. - Anonymous

October 16, 2017

I don't see await SynchronizationContextRemover.Instance; in your repo (the singleton suggested by Stephen Cleary). Is there a reason why a singleton would not be better?- Anonymous

October 20, 2017

I think its fine either way. With this item being a struct, it doesn't generate any extra garbage anyway. I remember stepping through this very carefully last time and ended up preferring not to use a singleton but I don't recall exactly why.

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

August 30, 2018

I noticed that this approach still results in deadlock when the SynchronizationContext comes from using Stephen Cleary's Nito.AsyncEx.AsyncContext.I haven't investigated why, yet. Shouldn't SynchronizationContextRemover work with any sync context?